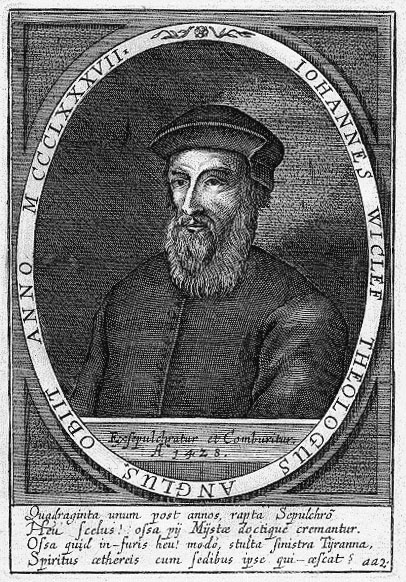

John Wycliffe (c. 1320 – 1384)

On December 31, 1384, English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, priest, and Oxford seminary professor John Wycliffe passed away. Wycliffe became an influential dissident within the Roman Catholic priesthood during the 14th century and is considered an important predecessor to Protestantism. Wycliffe advocated translation of the Bible into the common vernacular. In 1382 he completed a translation directly from the Vulgate into Middle English – a version now known as Wycliffe’s Bible.

“I believe that in the end the truth will conquer.”

– John Wycliffe, Statement to the Duke of Lancaster (1381), as quoted in Champions of the Right (1885) by Edward Gilliat

John Wycliffe – Early Years

Wycliffe was born in the village of Hipswell near Richmond in the North Riding of Yorkshire, England, around the 1320s. His family was long settled in Yorkshire. It is not known when he first came to Oxford, with which he was so closely connected until the end of his life, but he is known to have been at Oxford around 1345. In May 1361 Wycliffe became rector of the benefice of Fillingham (Lincolnshire), which belonged to Balliol. This and other benefices enabled Wycliffe to finance his studies; in 1363 he was admitted to the study of theology. He served as head of Balliol College, Oxford, and in 1365/67 was head of the new college, Canterbury-Hall. After his removal, there was an internal break with the church, and Wycliffe turned to politics in London. While as a doctor of theology he had the right to give theological lectures, he was also a parish priest in posts given by secular princes. The parish of Fillingham was followed in 1368-1374 by Ludgershall (Buckinghamshire), and finally in 1374-1384 by the rich parish of Lutterworth (Leicestershire), which he received in gratitude for his services to the crown from the future English regent John of Ghent.

Unique Authority of the Bible

Wycliffe proclaimed the doctrine of “unique authority of the bible” according to which God himself directly confers all authority, denied the pope’s claim to political power. In his works from 1372 to 1380, he advocated the complete subordination of the church to the state. He supported the secular rulers’ will to power in several lawsuits against the pope and demanded a life of Original Christian modesty for church employees, although he himself lived well from his rich benefice until his death.

Complaints against the Papal See

In 1373, King Edward III sent him to Bruges with other clergymen to present complaints against the papal see to the papal nuncio, in particular the curia was accused of selling church offices. The “complaints” served to further suspend the contractually agreed annual payments to Rome that had been outstanding for 33 years. Wycliffe’s cause prevailed in 1375. As official prosecutor on behalf of the king, Wycliffe now gave himself the title “Pecularius regis clericus” (Royal Chaplain).

Fight Against Papal Antichristianity

His juridical-theological and political influence on the compilation of royal complaints against the pope presented to the Good Parliament in 1376 was great. A lawsuit against the pope, which Wycliffe had lost on his own in 1370, was crowned by that over outstanding payments in 1373-1375, in which he prevailed. This culminated in 1377 in a lawsuit brought by the pope against sententiae from Wycliffe’s works, which, thanks to Wycliffe’s great reputation at the university and among the people, came to nothing in 1378. Encouraged by this, Wycliffe now openly opposed the political influence of the clergy altogether and fought papal “antichristianity.”

Trialogus

In his major work, the Trialogus, Wycliffe taught pantheistic realism, determinism, and double predestination (determinatio gemina). He taught, “Everything is God; every being is everywhere, since every being is God,” and “Everything that happens happens with absolute necessity, even evil happens with necessity, and God’s freedom consists in willing what is necessary.” He consequently disapproved of veneration of images, saints, relics, and priestly celibacy, rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation and auricular confession because of his realism. Reddish-clad itinerant preachers trained by him ( called “poor priests”) spread principles among the people reminiscent of Protestant teachings 150 years later. His teachings met with approval among large segments of the population and significantly influenced the English peasants’ revolt of 1381.

Translating the Bible

“This Bible is for the Government of the People, by the People, and for the People.”

– John Wycliffe, General Prologue to the Bible translation of 1384

Meanwhile, mendicant monks in league with the hierarchy enforced the rejection of his teachings by the university in 1381 and the synod meeting in London in 1382. His writings were condemned as heretical by the synod at Oxford, and he lost his offices at court in regard to church affairs. However, for fear of a popular uprising, Wycliffe was not officially charged. He quietly continued his parish ministry, and in 1383 completed a collection of early English Bible translations from the Vulgate into the vernacular that he had begun earlier. This translation of the Bible is not the first translation into English, but represents a compilation and revision of earlier translations, as already noted by Thomas More in 1530 and demonstrated by Francis Aidan Gasquet OSB in 1897.

Wycliffe died in 1384 as the result of a stroke during Mass in Lutterworth (now Harborough District, Leicestershire).

Legacy

The later followers of Wycliffe’s ideas, the Lollards, were not harshly persecuted by the English state until after an unsuccessful revolt beginning in 1400. In 1401, William Sawtrey became their first martyr. However, the sometimes brutal inquisition of European heretics, such as the Cathars or Waldensians, cannot be compared to the English persecution. The latter was characterized by its relative leniency and consideration for the Lollards who continued to live underground, so that in many families Wycliffe’s views survived until the Reformation. In 1412, at the end of the English king’s persecution, 267 of Wycliffe’s sentences were condemned as heretical in London. Three years later the Council of Constance determined to burn all Wycliffe’s writings, and 30 years after his death on May 4, 1415, declared him a heretic, condemned another 45 sententiae of his, and ordered his bones to be dug up and burned, which was actually done thirteen years later, in 1428, by Bishop Richard Fleming of Lincoln.

Ryan M Reeves, John Wycliffe, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Latin Works of John Wyclif, e-Texte, Center for Medieval Studies, Fordham University

- [2] Lahey, Stephen. “Wyclif’s Political Philosophy”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [3] John Foxe, “An Account of the Life and Persecutions of John Wickliffe,” The Book of Martyrs.

- [4] “Wycliffe, John“. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- [5] Works by or about John Wycliffe at Internet Archive

- [6] Buddensieg, Rudolf (26 October 1884). “John Wiclif, patriot & reformer; life and writings”. London : T. Fisher Unwin.

- [7] John Wycliffe at Wikidata

- [8] Ryan M. Reeves, John Wycliffe – Morning Star of the Reformation, Chruch History at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Ryan Reeves @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of Translators of the Bible into English, via Wikidata and DBpedia