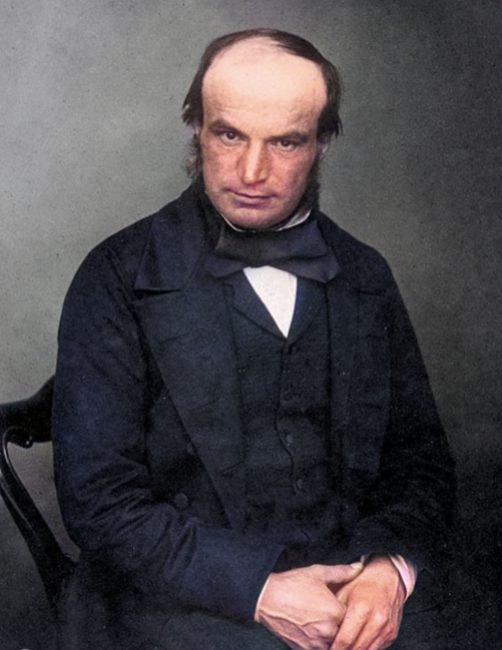

John Couch Adams (1819-1892)

On January 21, 1821, English mathematician and astronomer John Couch Adams passed away. Adams most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position of Neptune, using only mathematics. The calculations were made to explain discrepancies with Uranus‘s orbit and the laws of Kepler and Newton. At the same time, but unknown to each other, the same calculations were made by Urbain Le Verrier.[5]

Youth and Education

John Couch Adams was born at Lidcot, a farm at Laneast, Cornwall, the eldest of seven children, to Thomas Adams, a poor tenant farmer, and his wife, Tabitha Knill Grylls. From an early age on John Couch Adams was intrigued by astronomy books he found in the small inherited library of his mother’s uncle. He attended the Laneast village school where he acquired some Greek and algebra. He continued in a private school of his mother’s cousin, the Rev. John Couch Grylls, where he learned classics but was largely self-taught in mathematics. He observed Halley’s comet in 1835 and the following year started to make his own astronomical calculations, predictions and observations, engaging in private tutoring to finance his activities. He worked out that an annular eclipse of the Sun would be visible in Lidcot in 1836, and he was there to make the observations.[1]

In 1836, his mother inherited a small estate at Badharlick and his promise as a mathematician induced his parents to send him to the University of Cambridge. In 1839 he entered as a sizar at St John’s College, graduating B.A. in 1843 as senior wrangler and first Smith’s prizeman of his year. He did not spend all his time on research, however, for he tutored undergraduates so that he might earn money to send home to help with his brother’s education.[1]

Unregularities in the Motion of Uranus

On 3 July 1841, while still an undergraduate, Adams made a note that he had decided to investigate the irregularities of the motion of Uranus.[1] In 1821, French astronomer Alexis Bouvard had published accurate astronomical tables of the orbit of Uranus, making predictions of future positions based on Newton’s laws of motion and gravitation. Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations of Uranus’ position from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesize some perturbing body. Adams became convinced of the “perturbation” theory. He believed, in the face of anything that had been attempted before, that he could use the observed data on Uranus, and utilizing nothing more than Newton’s law of gravitation, to deduce the mass, position and orbit of the perturbing body.

After his final examinations in 1843, Adams was elected fellow of his college and spent the summer vacation in Cornwall calculating the first of six iterations. Adams communicated his work to James Challis,[7] director of the Cambridge Observatory, in mid-September 1845 but there is some controversy as to how. Adams, returning from a Cornwall vacation, without appointment, twice called on Astronomer Royal George Biddell Airy in Greenwich. Failing to find him at home, Adams reputedly left a manuscript of his solution, again without the detailed calculations [6]. Airy responded with a letter to Adams asking for some clarification. Meanwhile, Urbain Le Verrier, on 10 November 1845, presented to the Académie des sciences in Paris a memoir on Uranus, showing that the pre-existing theory failed to account for its motion. On reading Le Verrier’s memoir, Airy was struck by the coincidence and initiated a desperate race for English priority in discovery of the planet.

“The Brits stole Neptune”

The search was begun by a laborious method on 29 July. It was Le Verrier’s prediction which led to the discovery of Neptune on 23 September 1846 by Galle at the Berlin Observatory.[8] Only after the discovery of Neptune had been announced in Paris did it become apparent that Neptune had been already observed on 8 and 12 August but because Challis lacked an up-to-date star-map it was not recognized as a planet. A keen controversy arose in France and England as to the merits of the two astronomers. As the facts became known, there was wide recognition that the two astronomers had independently solved the problem of Uranus, and each was ascribed equal importance. However, there have been subsequent assertions that “The Brits Stole Neptune” and that Adams’s British contemporaries retrospectively ascribed him more credit than he was due. The disparity between the credit accorded to Le Verrier and that accorded to Adams was not made up for some years, but the two men met at Oxford in 1847 and became good friends.[3]

Further Achievements

Adams’ lay fellowship at St John’s College came to an end in 1852, and the existing statutes did not permit his re-election. However, Pembroke College, which possessed greater freedom, elected him in the following year to a lay fellowship which he held for the rest of his life. Despite the fame of his work on Neptune, Adams also did much important work on gravitational astronomy and terrestrial magnetism. In 1852, Adams published new and accurate tables of the moon’s parallax, which superseded Johann Karl Burckhardt‘s, and supplied corrections to the theories of Marie-Charles Damoiseau, Giovanni Antonio Amedeo Plana, and Philippe Gustave Doulcet. After being made professor of mathematics at the University of St. Andrews (Fife) in 1858 and Lowndean professor of astronomy and geometry at Cambridge in 1859, Adams became director of Cambridge Observatory in 1861.[2]

Meteors and Comets

Adams’s made many other contributions to astronomy, notably his studies of the Leonid meteor shower. He predicted correctly in 1864 that the meteor shower would occur in November 1866. Calculating the orbit was an extremely difficult task since the effect of planetary perturbations had to be taken into account. In March 1867 he showed that the orbit of the meteor shower was very similar to that of Tempel’s comet. He was able to correctly conclude that the meteor shower was associated with that comet.[1] Adams spent much effort on the complex problem of a description of the motion of the Moon, giving a theory which was more accurate than that of Laplace.[9] He began this work in 1851 when elected as President of the Royal Astronomical Society and he presented a paper to the Royal Society in 1853 in which he showed that Laplace had omitted terms from his equations which were not negligible.[1]

Later Life

In 1870 the Cambridge Observatory acquired a Simms transit circle. In order to exploit it fully, Adams undertook — a rarity for him — the direction of a program of observational astronomy. The circle was used to map a zone lying between 25° and 30° of north declination for the Astronomische Gesellschaft program. This work was first published in 1897. In 1874 Adams was elected to a second term as president of the Royal Astronomical Society. His scientific interest at this time turned to mathematics. Like Euler and Gauss, Adams enjoyed the calculation of exact values for mathematical constants.[3]

The post of Astronomer Royal was offered him in 1881, but he preferred to pursue his teaching and research in Cambridge. In October 1889 Adams became seriously ill with a stomach haemorrhage. John Couch Adams died in 1892, aged 72, in the Cambridge Observatory.

Richard Feynman: On Discovery of Neptune, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “John Couch Adams“, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- [2] John Couch Adams, British astronomer, at Britannica Online

- [3] John Couch Adams at zbMATH

- [4] John Couch Adams at Wikidata

- [5] Urbain Le Verrier and the hypothetical Planet Vulcan, SciHi Blog, January 2, 2014.

- [6] The Astronomical Achievements of Sir George Biddell Airy, SciHi Blog, July 25, 2017.

- [7] James Challis and his failure to discover the planet Neptune, SciHi Blog

- [8] Johann Gottfried Galle and the First Observation of Planet Neptune, SciHi Blog

- [9] Pierre Simon de Laplace and his true love for Astronomy and Mathematics, SciHi Blog

- [10] Richard Feynman: On Discovery of Neptune, RichardFeynmanLove @ youtube

- [11] [Anon.] (1892). “John Couch Adams”. Astronomical Journal. 11: 112.

- [12] J. W. L. Glaisher (1892). “Obituary: John Couch Adams”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 53: 184–209.

- [13] Kollerstrom, Nick (2001). “Neptune’s Discovery. The British Case for Co-Prediction”. University College London.

- [14] Timeline of Discoveries in the Solar System, via Wikidata

- [15] Works written by or about John Couch Adams at Wikisource