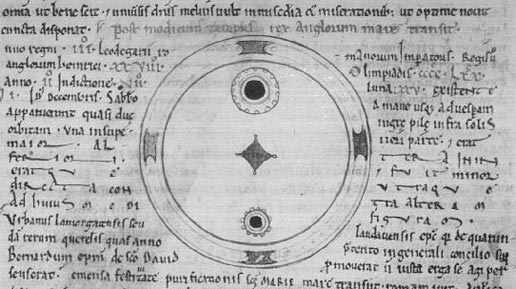

A drawing of a sunspot in the Chronicle of John of Worcester.

Probably on June 13, 1611, Frisian astronomer Johannes Fabricius published his Narratio de maculis in sole observatis et apparente earum cum sole conversione (Account of Spots Observed on the Sun and of Their Apparent Rotation with the Sun), which counts as the first published description of sunspots. Nevertheless, sunspots have been discovered earlier, as the first record of a sunspot drawing dates back into the 12th century to John of Worcester in 1128.

Johannes Fabricius – Early Life

Johannes was born in Resterhafe (East Friesland). He was the eldest son of eight children of the pastor and astronomer David Fabricius,[4] who conducted extensive astronomical and meteorological research and was in correspondence with Tycho Brahe,[5] Johannes Kepler [6] and Simon Marius.[7] Like his father, Fabricius attended the University of Helmstedt. Besides the usual basic studies at the Faculty of Philosophy, he also worked in medicine. However, he moved to the University of Wittenberg in 1606, where he remained for three years and studied geometry, astronomy, chronology and physics in addition to grammar, dialectics and rhetoric. In addition to astronomy, like his father, he was involved in astrology and was convinced that it provided reliable information. He also believed he had found a method of weather forecasting.

The Observation of Sunspots

In 1609 Fabricius went to Leiden to study medicine at the university there. When he returned to Wittenberg in the following year, he brought with him with telescopes that he and his father used for astronomical observation, including the observation of the Sun. Fabricius noted the existence of sunspots, being the first confirmed instance of their observation. Since direct observation of the sun damages the eye, Fabricius and his father soon applied a safer method of indirect observation: Using a pinhole they directed the sunlight into a darkened room and looked at the sun disk on a white piece of paper (the principle of the camera obscura). The existence of the sunspots could be proven without any doubt. Their daily movement on the sun disk was aptly attributed to a self-rotation of the sun. In June of the same year, Johann Fabricius published a 22-page book De Maculis in sole observatis et apparente earum cum Sole conversione narratio in Wittenberg, in which he describes all the details of the discovery and credits his father with a due share.

Title page of De Maculis in sole observatis et apparente earum cum Sole conversione, Narratio (1611)

A Brief History of Solar Observations

Solar activities and their related events in general have probably already been observed by the Babylonians. It is further believed that sunspots were mentioned by the ancient Greek scholar Theophrastus, a disciple of Plato and Aristotle. The earliest surviving record of deliberate sunspot observation dates from 364 BC, based on comments by Chinese astronomer Gan De in a star catalogue. The first known drawing of sunspots dates back to John of Worcester in 1128. Also Benedictine monk Adelmus probably observed a large sunspot that was visible for eight days, but he concluded to be observing the transit of Mercury. Also Galileo and Christoph Scheiner probably observed sunspots, unaware of Fabricius’ work.[3] In 1613 Galileo refuted Scheiner’s 1612 claim that sunspots were planets inside Mercury’s orbit, showing that sunspots were surface features.

Scientific Explanations

The observations on sunspots continued, but the physical aspects of sunspots were not identified until the 20th century.Sunspots were rarely recorded between 1650 and 1699. Later analysis revealed the problem to a reduced number of sunspots, rather than observational lapses.British astronomer Edward Maunder suggested that the Sun had changed from a period in which sunspots all but disappeared to a renewal of sunspot cycles starting in about 1700. Adding to this understanding of the absence of solar cycles were observations of aurorae, which were absent at the same time. The lack of a solar corona during solar eclipses was also noted prior to 1715. The period of low sunspot activity from 1645 to 1717 later became known as the “Maunder Minimum”. In 1848, Joseph Henry projected an image of the Sun onto a screen and determined that sunspots were cooler than the surrounding surface. The emission of higher than average amounts of radiation later were observed from the solar faculae. Sunspots had some importance in the debate over the nature of the Solar System. They showed that the Sun rotated, and their comings and goings showed that the Sun changed, contrary to Aristotle, who had taught that all celestial bodies were perfect, unchanging spheres. This discovery contrasted also the Church’s doctrine that the sun should be “unpolluted”, as the Virgin Mary were.

Almost nothing is known about Fabricius’ later life. Apparently, he initially continued his medical studies. Johannes Fabricius died in Marienhafe, today Lower Saxony, on 19 March 1616 at the age of 29 on a trip to Basel, where he wanted to obtain his medical doctorate.

The Inconsistent Sun – Professor Claudio Vita-Finzi, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] History of Solar Physics: A Time Line of Great Moments

- [2] Johannes Fabricius in the Biographical Encyclopedia of Britannica

- [3] Galileo Galilei and his Telescope, SciHi Blog

- [4] David Fabricius and the Wonders of the Heavens, SciHi Blog

- [5] Tycho Brahe – The Man with the Golden Nose, SciHi Blog

- [6] And Kepler Has His Own Opera – Kepler’s 3rd Planetary Law, SciHi Blog

- [7] Simon Marius and his Astronomical Discoveries, SciHi Blog

- [8] Johannes Fabricius at Wikidata

- [9] Spotting the spots, at The Renaissance Mathematicus, Jan 8, 2011

- [10] The Inconsistent Sun – Professor Claudio Vita-Finzi, Gresham College @ youtube

- [11] Willy Jahn (1959), “Fabricius, Johannes”, Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 732

- [12] “Johann Fabricius (1587-1616)”. hao.ucar.edu. High Altitude Observatory.

- [13] Timeline of German astronomers, via DBpedia and Wikidata