Eiger Northface. Photo by Terra3, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On July 21, 1938, Austrian mountaineer, sportsman, and geographer Heinrich Harrer together with Andreas Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, and Fritz Kasparek started ther first successful climb of the famous Eiger north face, which is the biggest north face in the Alps. The north face is considered amongst the most challenging and dangerous ascents in the European alps.

A Top Sportsman

Heinrich Harrer was born in 1912 in Hüttenberg, Austria-Hungary, in the district of Sankt Veit an der Glan in the state of Carinthia. His father was a postal worker. He studied geography and sports at the Karl-Franzens University in Graz. However, Harrer’s true passion was mountain climbing. At the age of fifteen he made his first climbing attempts in the Julian Alps. At the age of sixteen he began to take part in ski competitions. In the winter semester 1933/1934 he became active with the A.T.V. Graz, became 1937 academic downhill world champion, later (1958) also Austrian golf champion. From 1933 to 1938 he studied geography and sports at the Karl Franzens University in Graz. He financed his studies by holding ski and climbing courses, among other things – after successfully passing his ski instructor and mountain guide exams. He founded a ski school on the Tauplitz, where he was also responsible as a hut warden for the club’s own refuge Grazer Haus, and also worked in Sesto in the Dolomites. In order to win a place on a Himalayan expedition, Harrer and his friend Fritz Kasparek wanted to be the first to successfully climb the North Face of the Eiger in Switzerland. The difficult and almost vertical wall had already claimed several lives prior to their ascend and the Bernese authorities even banned climbing it.

The Eiger North Face – Death Bivouc

In 1935, the two German climbers Karl Mehringer and Max Sedlmeyer made the first attempt on the Eiger north face. After reaching the height of the Eigerwand station, the climbers made their first bivouac. Unfortunately, they were surprised by bad weather and gained only little height. During the third night, a storm broke out, followed by fresh snow. Averlanches of snow came down the Eiger north face and the clouds closed over it. When the weather cleared up, the men were spotted a bit higher and about to bivouac for the fifth time. Then the fog hid the climbers again, when the weather finally cleared a completely white north face resealed. Both climbers were found frozen to death a few days later. The place then became known as “Death Bivouac“.

A Death Trap

During the following year, another disaster occurred at the Eiger north face. Ten climbers gathered at Grindelwald, camping at the mountain’s foot. Unfortunately, one climber died during a training climb. Further, the weather became so bad over the summer that the climbers had to wait a long time for their turn. Many of them gave up and left, only four climbers remained: Andreas Hinterstoisser and Toni Kurz from Germany, and Willy Angerer and Edi Rainer from Austria. After a weather improvement the men began to ascend the face. At first, the climbed quickly but after their first bivouac, the weather changed. After the weather cleared up a little bit, the climbers were seen to descend the mountain. Since Angerer was seriously injured from a falling rock they had no choice but to give up. However, they became stuck because they were not able to recross the difficult Hinterstoisser Traverse. Ultimately, an avalanche swept them away which only Toni Kurz survived hanging on a rope. The rescue attempt was dangerous and took a long time and the guides were not able to get Kurz down alive. Before he passed away slowly hanging from a rope, Kurz explained to the rescue team that one of the climbers fell form the north face, another froze to death and the third had fractured his skull in falling and was hanging dead on the rope. One year later, Mathias Rebitsch and Ludwig Vörg attempted to climb the Eiger north face. Even though they were unsuccessful, they were the first to return alive.

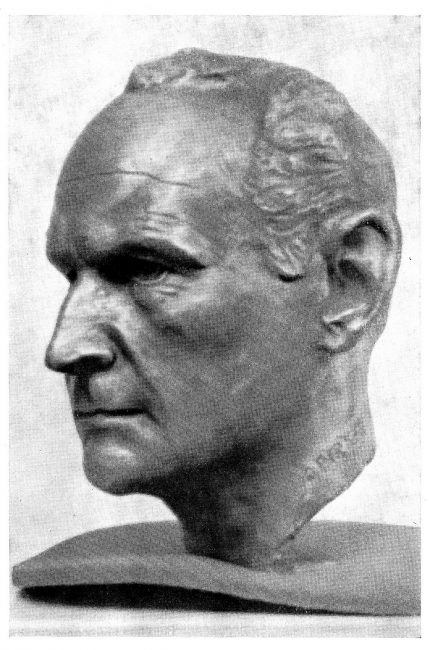

Heinrich Harrer (1912-2006), Bust by Alfred Pirker

A Glorious Moment in the History of Mountaineering

In 1938, the north face finally was ascended successfully for the first time by Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek in a German-Austrian party. While originally the climbers started in two seperate groups, they joined forces later on. Heckmair later wrote: “We, the sons of the older Reich, united with our companions from the Eastern Border to march together to victory.” On the third day of the expedition, the group was hit by a storm and it became extremely cold. They were caught in an avalanche when climbing “the Spider,” the snow-filled cracks radiating from an ice-field on the upper face, but all possessed sufficient strength to resist being swept off the face. Harrer and the other three climbers successfully reached the summit in the afternoon. They were so exhausted that they only just had the strength to descend by the normal route through a raging blizzard.

This first ascent of the Eiger North Face was described by the famous Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner as “a glorious moment in the history of mountaineering and a great sensation, since several climbers had previously perished on the Face“.

The Nanga Parbat Expedition and Interim Camps

In the summer of 1939, an exploratory expedition to Nanga Parbat had taken place organized by the German Himalaya Foundation, in which Harrer had participated. When the Germans waited in Karachi at the end of August for the overdue cargo ship to return home, they were detained because of the Second World War, which began on 1 September 1939: first in interim camps, then, after England entered the war on 3 September, in the British internment camp in Ahmadnagar near Bombay; at last they were transferred to Dehra Dun at the foot of the Himalayas.

The Flight to Tibet

Several of the internees wanted to break out and break through to Japanese lines: Harrer succeeded in breaking out in 1944, for the fifth time. Harrer and the other escapees wanted to reach the Japanese lines in the east via Tibet, which can be regarded as neutral. In Tibet, however, it turned out that it was forbidden for Tibetans to sell food to strangers without a permit. Although these could occasionally be acquired at black market prices, the funds would not have sufficed for long. Harrer and his fellow climber Peter Aufschnaiter planned to reach Lhasa and throughout the entire journey, the two covered at least 50 passes – none under 5,000 metres – and covered around 2,100 kilometres on foot. On January 15, 1946 they reached the then “forbidden city” of Lhasa.

Meeting the Dalai Lama

Aufschnaiter became an advisor to the Tibetan government on agricultural and urban development issues, Harrer first worked as a translator and photographer for the Tibetan government, later as a teacher and finally as a friend and teacher of the young 14th Dalai Lama, for whom he also renovated a private cinema. A cordial relationship connected them until Harrer’s death.

Returning to Europe

In 1952 Harrer returned to Europe and settled in Kitzbühel. Later he also lived temporarily in the hamlet of Münichau near Kitzbühel and in Liechtenstein. As an author he wrote over 20 books. His most famous work is Seven Years in Tibet, in which Harrer describes his time with Peter Aufschnaiter in Tibet and his acquaintance with the 14th Dalai Lama. He began to write about these experiences already in India. The book became a worldwide success (translated into 53 languages, worldwide circulation so far over 4 million) and made it famous. In 1997 Jean-Jacques Annaud filmed the book under the same title with Brad Pitt in the role of Heinrich Harrer. Heinrich Harrer died on 7 January 2006 at the age of 93.

Archivradio 11.12.1957 Heinrich Harrer über seine “Sieben Jahre in Tibet”, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Heinrich Harrer at the New York Times

- [2] Heinrich Harrer at Zeit Online (in German)

- [3] Heinrich Harrer at Britannica Online

- [4] Obituary in The Times, 9 January 2006

- [5] Works by or about Heinrich Harrer at Internet Archive

- [6] Martin, Douglas (10 January 2006). “Heinrich Harrer, 93, Explorer of Tibet, Dies”. The New York Times.

- [7] Heinrich Harrer im Historischen Alpenarchiv der Alpenvereine in Deutschland, Österreich und Südtirol

- [8] Holger Kreitling: Heinrich Harrer, ein Leben mit Tibet, SS und CIA. In: Die Welt. 5. Juli 2012.

- [9] Heinrich Harrer at Wikidata

- [10] Archivradio 11.12.1957 Heinrich Harrer über seine “Sieben Jahre in Tibet”, Kalenderblatt @ youtube

- [11] Timeline of Austrian Explorers, via DBpedia and Wikidata