Friedrich Spee (1591-1635)

On February 25, 1591, German Jesuit and poet Friedrich Spee was born, who is best known for his book Cautio Criminalis, in which he argued publicly against the trials for witchcraft and against torture in general. He was one of the noblest and most attractive figures of the awful era of the Thirty Years’ War.

Friedrich Spee and the Thirty Years War

Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld was born to a noble family at Kaiserswerth near Düsseldorf on the Rhine in Germany. On finishing his early education at Cologne, he entered the Society of Jesus in 1610. After prolonged studies and activity as a teacher at Trier, Fulda, Würzburg (a centre of the witchcraft persecutions), Speyer, Worms, and Mainz, was ordained priest in 1622. Two years later he became professor of moral theology at the University of Paderborn. His original wish to become a missionary in India was never granted by the Society. By this time Germany had entered into the turbulent times of the Thirty Years’ War, a series of conflicts lasting from 1618 to 1648 caused mainly by Protestant and Roman Catholic factions during the Reformation. Starting from 1626 he taught at Speyer, Wesel, Trier, and Cologne, and was preacher at Paderborn, Cologne, and Hildesheim. While working in Peine on the 20th April 1629, Spee was a target of an attempted assassination and was seriously wounded. He resumed his activity as professor and priest at Paderborn and later at Cologne, and in 1633 removed to Trier. During the storming of Trier by the imperial forces in the course of the Thirty Years’ War in March, 1635, he distinguished himself in the care of the suffering, and died soon afterwards from the results of an infection contracted in a hospital.

The Cautio Criminalis

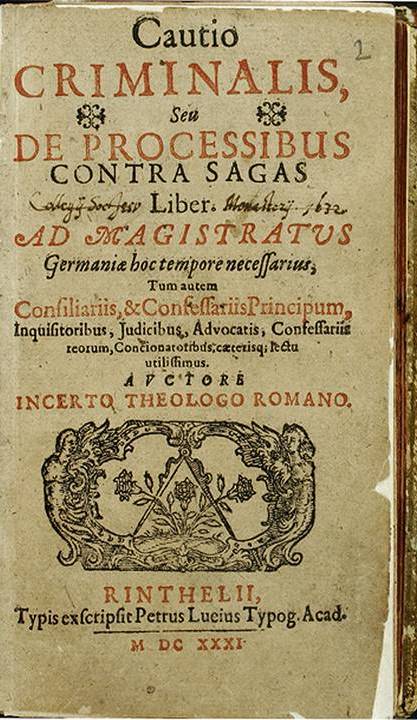

During the early 17th century at the height of some of the worst atrocities being perpetrated against witches in Germany, Friedrich von Spee was one of the first people in that country to effectively speak out against the witchcraft delusion. Following two bad harvests in 1626 and 1628 the population of Germany sought to release their frustrations with increased persecutions against witches. In the following years 600 witches were condemned in nearby Bamberg and a further 900 witches burned alive in Würzburg, places where the Prince Bishops of both were particularly zealous about hunting down and burning witches. The publication of Cautio Criminalis (Precautions for Prosecutors), written in admirable Latin, in 1631 put Spee’s relations with the Jesuit hierarchy under considerable strain, even jeopardizing for a time his membership of the Society.

Cautio Criminalis contains 52 questions which Spee argued and attempted to answer. Amongst his more notable conclusions were:

- (17) That alleged witches should be provided a lawyer and a legal defense, the enormity of the crime making this right even more important than normal.

- (20) That there is a real risk that innocents will confess under torture simply to stop the pain.

- (25) That condemning alleged witches for not confessing under torture is absurd. Spee opposed the notion that such silence was itself evidence of sorcery, as this made everyone guilty.

- (27) That torture does not produce truth, since those who wish to stop their own suffering can stop it with either the truth or with lies.

- (44) That denunciations of accomplices by tortured “witches” were of little value: either the tortured person was innocent, in which case she had no accomplices, or she was really in league with the Devil, in which case her denunciations could not be trusted either.

First printing of the Cautio Criminalis 1631

An Arrangement of Trial for Witchcraft

The book is an arraignment of trial for witchcraft, based upon his own awful experiences probably made in Westphalia. It is thought that Spee acted for a long time as “witch confessor” in Würzburg, as he seems to have knowledge of what could be considered the private thoughts of the condemned. The work was printed in 1631 at Rinteln without Spee’s name or permission, although he was doubtlessly widely known as its author.

Many people who incite the Inquisition so vehemently against sorcerers in their towns and villages are not at all aware and do not notice or foresee that once they have begun to clamor for torture, every person tortured must denounce several more. The trials will continue, so eventually the denunciations will inevitably reach them and their families, since, as I warned above, no end will be found until everyone has been burned. (Cautio Criminalis, question 15)

Further Literary Achievements

Spee’s literary activity was largely confined to the last years of his life, the details of which are relatively obscure. Two of his works were not published until after his death: Goldenes Tugendbuch (Golden Book of Virtues), a book of devotion highly prized by Leibniz, and Trutznachtigall (Rivaling the Nightingale), a collection of fifty to sixty sacred songs, which take a prominent place among religious lyrics of the 17th century and have been repeatedly printed and updated through the present. Spee wrote the lyrics and tunes of dozens of hymns, and is still the most heavily attributed author in German Catholic hymnals today. Although an anonymous hymnist during his lifetime, today he is credited with several popular works including the Advent song “O Heiland, reiß die Himmel auf“, the Christmas carols “Vom Himmel hoch, o Engel, kommt” and “Zu Bethlehem geboren“, and the Easter hymn “Lasst uns erfreuen” widely used with the 20th-century English texts “Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones” and “All Creatures of Our God and King“.

On August 7, 1635, Friedrich Spee died of the plague while tending the sick at Trier. He was only 44 years of age.

Teofilo Ruiz, The Terror of History: The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe, UCLA, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Friedrich Spee at the Catholic Encyclopedia

- [2] Friedrich Spee at controversial.com

- [3] Homepage of the Friedrich Spee Society

- [4] Digitized version of the original Cautio Criminalis

- [5] The Case of the Last Condemned With – Anna Göldi, SciHi Blog, June 13, 2012.

- [6] Let Us Calculate – the Last Universal Academic Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, SciHi Blog

- [7] Friedrich Spee at Wikidata

- [8] Friedrich Spee at Reasonator

- [9] Teofilo Ruiz, The Terror of History: The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe, 2007, UCLA @ youtube

- [10] Guido Maria Dreves: Spee, Friedrich von. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 35, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1893, S. 92–94.

- [11] Bernhard Schneider: Spee, Friedrich. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0, S. 641–643

- [12] Timeline of people convicted of witchcraft, via Wikidata