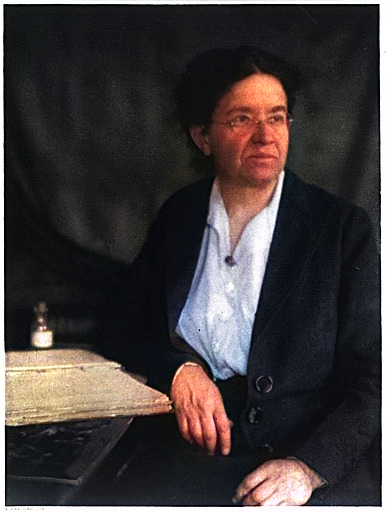

Florence Sabin (1871 – 1953)

On November 9, 1871, American medical scientist Florence Rena Sabin was born. She was a pioneer for women in science. She was the first woman to hold a full professorship at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences, and the first woman to head a department at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research.

Florence Sabin Background

Florence Rena Sabin was born in Central City, Colorado, to her father George K. Sabin, a mining engineer living and working on site with his family. Florence’s mother was a schoolteacher who later died from puerperal fever (sepsis) in 1878. Hence, Florence grew up with her Uncle Albert Sabin in Chicago and then with their paternal grandparents in Vermont. Throughout her childhood Sabin had intentions of becoming a pianist, however, she was never musically talented, causing her to shift her focus on a future in science during high school.

Academic Career

After graduating from Smith College in 1893, she first worked as a teacher of mathematics and zoology to finance her medical studies at Johns Hopkins University. In 1901, after successfully completing her doctoral studies, she became the first woman to be appointed professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1917, and eventually became the director of the Institute of Anatomy. She became a Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences in 1924, after the admission of female members. In the same year Florence Sabin became the first female president of the American Association of Anatomists.

Origin of the lymph vessels from the blood vessels

Sabin’s scientific achievements include her meticulous staining experiments on animal embryos, with which she wanted to clarify the question of where the lymph vessels of vertebrates originate, a question that had been discussed for a good 200 years at the time. Two hypotheses were opposed to each other: Many anatomists, like the physician G. Lovell Gulland, believed that the fluid that accumulates in the connective tissue exerts pressure on the neighboring cells and thus creates cavities that connect with each other and finally come into contact with the blood vessels. The anatomists George S. Huntington and Charles F. W. McClure also advocated such a centripetal model (expansion of the embryonic lymphatic system from the periphery towards the center). They examined histological sectional series of cat embryos and believed to recognize that the first endothelial cells of the lymphatic vessels are formed from isolated precursor cells in the mesenchyme. These lymphatic endothelial cells would first form a network and only then connect to the blood vessel system to drain lymph from the tissue into the blood.

Florence Sabin was convinced that sectional series could not provide reliable information about the spread of the developing lymphatic system and about connections between lymph vessels and blood vessels, and instead relied on the injection of ink into the first lymph-vessel-like structures in pig embryos of different ages. She saw that bud-like lymphatic sacs form at the cardinal veins, which then extend and connect with each other by sprouting, creating a network. This lymphatic network spreads from the center (the cardinal veins) to the periphery (centrifugal model). As part of her projects, Sabin produced a 3D model of a newborn baby’s brainstem. This project was considered successful and the textbook ‘An Atlas of the Medulla and Midbrain‘ was published as a result in 1901.

It was not until the beginning of the 21st century that molecular, genetic and imaging techniques were available to truly track the fate of cells as they developed (so-called Fate mapping or Lineage tracing). It was shown that a large part of the lymphatic vessels of higher vertebrates actually originated from precursors in the endothelium of the cardinal veins and the blood vessels branching off from them in the embryo, as postulated by Sabin. However, a small proportion seems to be of non-venous origin in at least some organs and tissue types.

Cracking the Glass Ceiling

Sabin became an intern at Johns Hopkins Hospital followed by a research fellowship in the Department of Anatomy at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. She began to teach at the department in 1902 and was appointed full professor of embryology and histology in 1917. Florence Sabin was back then the first known woman in the position of the full professor at a medical college and the first female president of the American Association of Anatomists as well as the first lifetime woman member of the National Academy of Sciences. Sabin later focused her research on the origins of blood, blood vessels, blood cells, the histology of the brain, and the pathology and immunology of tuberculosis. She also became the head of the Department of Cellular Studies at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City.

After her retirement, Florence Sabin became involved in health projects in Colorado and published studies revealing the bad health situations all over the state. She fought against uninterested politicians and her effort was rewarded with new health bills which became known as the ‘Sabin Health Laws’. She took part in modernizing the public health system and became manager of health and charities for Denver, donating her salary to medical research. Florence Sabin passed away on October 3, 1953. [3]

Dr. John Campbell, Lymphatic System 1, Tissue fluid [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Florence Sabin at Britannica

- [2] Florence Sabin at John Hopkins College

- [3] Florence Sabin at the National Library of Medicine

- [4] Sabin, Florence R (February 2002). “Preliminary note on the differentiation of angioblasts and the method by which they produce blood-vessels, blood-plasma and red blood-cells as seen in the living chick. 1917”. J. Hematother. Stem Cell Res. 11 (1): 5–7.

- [5] Parkhurst, G. (January 1930). “Dr. Sabin, Scientist”. Pictorial ReviewJournal of Medical Biography: 2–3.

- [6] Florence Sabin at Wikidata

- [7] Dr. John Campbell, Lymphatic System 1, Tissue fluid, Dr. John Campbell @ youtube

- [8] Philip D. Mcmaster and Michael Heidelberger, “Florence Rena Sabin”, Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences (1960)

- [9] Timeline of Florence Sabin via Wikidata