Desiderius Erasmus Roterdamus by Hans Holbein the Younger

On October 27, 1466, Dutch Renaissance humanist, Catholic priest, social critic, teacher, and theologian Desiderius Erasmus Roterdamus, also known as Erasmus of Rotterdam was born. He was the dominant figure of the early-16th-century humanist movement. Besides others, he is also namesake of the European Erasmus funding programme, the world’s largest support programme for stays abroad at universities that financed about 1 million scholarships in its first 15 years.

“No Man is wise at all Times, or is without his blind Side.”

– The Alchymyst, in Colloquies of Erasmus, Volume I.

Erasmus Desiderius – Early Years

Erasmus was born as the illegitimate son of the Catholic Gouda priest Rotger Gerard († 1484) and the widowed Zevenberg doctor’s daughter Margaretha Rogerius († 1483), his housekeeper, probably in Rotterdam between 1464 and 1469. From 1478 to 1485, together with his brother, he attended the Latin School of the Brothers of Common Life, which belonged to the monastery of St. Lebuinus, where Alexander Hegius and Brother Johannes Synthius (ca. 1450-1533) taught him in Deventer. It was there that Erasmus heard and saw Rudolf Agricola, whom he regarded throughout his life as an example and inspiration, and his interest in classical antiquity literature was awakened. Originally Erasmus wanted to go to the university in Hertogenbosch after his school days, but a possible plague epidemic or the English sweat pandemic, Sudor Anglicus,[4] which first took away his mother and then his father, prevented him from attending the university. So his guardian decided to prepare the boy for a religious life.

Ordained Priest and Studies in Paris

“You must acquire the best knowledge first, and without delay; it is the height of madness to learn what you will later have to unlearn.”

– Erasmus of Rotterdam, Letter to Christian Northoff (1497)

In 1485 Erasmus left the Latin school without graduation, but with excellent knowledge of Latin. In 1487 Erasmus became a canon in the monastery of the Augustinian choirmasters, Klooster Emmaüs te Stein near Gouda. In April 1492 Erasmus was ordained priest as canon and in the following year he left the monastery as secretary in the service of the bishop of Cambrai Heinrich von Glymes und Berghes, which he later never entered again. From 1495 to 1499 he studied theology at the Sorbonne in Paris. The school faced increasing influences of the Renaissance humanism, which also showed impact on Erasmus.

A Traveling Scholar

“The most disadvantageous peace is better than the most just war.”

– Erasmus of Rotterdam, Adagia (1508)

Since November 1498 he was the educator of Lord Mountjoy and lived in his apartment in Paris. In the summer of 1499 he went with his student Lord Mountjoy to Bedwell in Hertfordshire, England. There he became acquainted with Thomas Morus and John Colet, later also with William Warham, John Fisher and the young Prince Henry, the later King Henry VIII. From 1500 to 1506 he stayed alternately in the Netherlands, in Paris and in England. He refused a call to the University of Leuven in 1502, when he had temporarily concentrated intensively on the translation of Greek texts. In 1506 he moved to Italy, where he travelled until 1509 and where he intensively studied writing. In Turin (Duchy of Savoy) he received a doctorate in theology, which earned him the title of Reichsbaron. In Venice he met the publisher Aldus Manutius and had some of his works printed by him.

Paris, Leuven, Basel

“In the country of the blind the one-eyed man is king.”

– Erasmus of Rotterdam, Adagia (first published 1500)

He then moved back to England, where he taught Greek at Cambridge University. Erasmus lectured at Queens’ College in Cambridge from 1510 to 1515. Archbishop William Warham appointed Erasmus Rector of St Martin’s Church in Aldington in 1511. There he lived in the vicarage next to the church, but since he spoke only Latin and Dutch, he could not fulfill his pastoral duties in English. Only one year later he resigned his office. He pushed kidney complaints forward, which he blamed on the local beer. He then commuted for years between England, Burgundy and Basel. Back from England, Erasmus worked for several years at the court of Burgundy in Leuven, among other things as an educator (councillor) of Prince Charles, the later Emperor Charles V. From 1514 to 1529 Erasmus lived and worked in Basel (Alte Eidgenossenschaft) and had his writings printed in the workshop of his later friend Johann Froben. Although Erasmus never studied or taught at the University of Leuven, he spent several months in Leuven in 1517 and helped found the Collegium Trilingue. This institution for the study of Latin, Greek and Hebrew was the first institution of its kind in Europe, where Greek and Hebrew texts were no longer studied in Latin translation but in their original versions. In 1518 the first edition of the Colloquia familiaria (“Familiar Conversations“), one of the most popular books of the 16th century, was published. Often regarded as his masterpiece, the book criticizes the abuses of the Church with courage and sharpness.

Freiburg and the Case of Thomas More

In 1524 he first met Johannes a Lasco, the later reformer of Friesland, who became one of his favourite pupils. When Johannes Oekolampad’s Reformation, based on Zwingli, prevailed in Basel, he went to Freiburg im Breisgau in 1529, where he rejected the Reformation as a priest and Augustinian canon. In May 1535 Erasmus received a visit from Raffaelo Maruffo, a friendly Genoese merchant. After a longer stay in England, he was on his way back to Italy and told him about the causa Morus. The Tudor King Henry VIII had declared himself the head of the English Church and ordered the former Lord Chancellor Thomas More in April 1534 to acknowledge this measure by an oath. Because More refused this, he – together with Bishop John Fisher of Rochester – was imprisoned in the Tower of London and brought to justice. On 18 June 1535 Erasmus reported about the unfortunate situation of the two accused in a letter to Erasmus Schedt in which he expressed his lack of understanding about the actions of Henry VIII. More was finally sentenced to death and beheaded on 6 July 1535 at the age of 57. After More’s death Erasmus found the praising words:

“Thomas More, Lord Chancellor of England, whose soul was purer than the purest snow, whose genius was as great as England never had, never will have again, though England is a mother of great spirits”.

In 1535 he returned to Basel and died there on 12 July 1536. The high reputation that Erasmus enjoyed despite his rejection of the Reformation was shown by the fact that he was buried as a Catholic priest in a time of fierce confessional conflicts in a cathedral that had meanwhile become Protestant.

A Prolific Writer

Erasmus spoke and wrote mostly in Latin, but he also spoke Greek. He was a fruitful author, according to today’s knowledge he has written about 150 books. In addition, more than 2000 letters have been received from him. Because of his subtle expression his letters enjoyed great attention in Europe. It is estimated that he wrote about 1000 words a day. His collected works were published in 1703 in ten volumes. He saw himself with the new printing technique as a mediator of education:

“People are not born as human beings, but educated as such!”

As a text critic, editor (Church Fathers, New Testament) and grammarian he founded modern philology. The pronunciation common today in Western countries, in particular the emphasis on ancient Greek, goes back to him.

The Praise of Folly

His most famous work today is the satire Praise of Folly (Laus stultitiae) from 1509, which he dedicated to his friend Thomas Morus. In this “style exercise” (as he called it) he countered deeply rooted errors with ridicule and seriousness and advocated reasonable views. For this he found the ironic words:

“The Christian religion is quite close to a certain foolishness; on the other hand, it does not get along well with wisdom”.

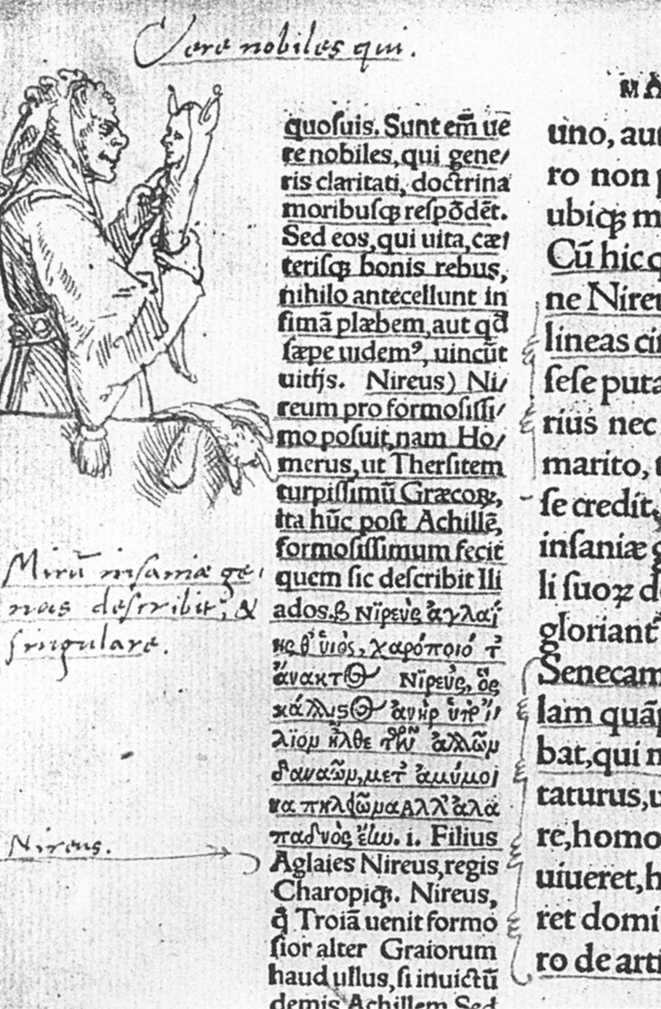

Marginal drawing of Folly by Hans Holbein in the first edition of Erasmus’s Praise of Folly, 1515

New Testament and Reformation

In 1516 Erasmus published a critical edition of the Greek New Testament, Novum Instrumentum omne, diligenter ab Erasmo Rot. Recognitum et Emendatum, with a new Latin translation and commentary, created by himself by revising the Vulgate. Erasmus’ New Testament was the first available complete printed Greek text of the New Testament. After the success of the first edition, he simply named the work Novum Testamentum from the second edition (1519) onwards. It was used by the translators of the King James Bible and also served Martin Luther [5] as the source text for his German Bible translation.”Free will does not exist“, according to Luther in his letter De Servo Arbitrio to Erasmus translated into German by Justus Jonas (1526), in that sin makes human beings completely incapable of bringing themselves to God. Noting Luther’s criticism of the Catholic Church, Erasmus described him as “a mighty trumpet of gospel truth” while agreeing, “It is clear that many of the reforms for which Luther calls are urgently needed.” He had great respect for Luther, and Luther spoke with admiration of Erasmus’ superior learning. In the years 1522 to 1534 Erasmus dealt with the teachings and writings of Luther in various writings. Two years before his death he tried once again with the script De sarcienda ecclesiae concordia to pacify the divided faith parties.

Han van Ruler, Who was this Erasmus Anyway?, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Erasmus and the Age of Reformation by Johan Huizinga

- [2] Charles L. Cortright, Luther and Erasmus: The Debate on the Freedom of the Will

- [3] Erasmus of Rotterdam at Stanford

- [4] John Caius and the English Sweating Sickness, SciHi Blog

- [5] Martin Luther – Iconic Figure of the Reformation, SciHi Blog

- [6] “Desiderius Erasmus”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [7] Works by or about Erasmus at Internet Archive

- [8] Erasmus at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [9] Erasmus of Rotterdam at Wikidata

- [10] Works by Erasmus of Rotterdam at Wikisource

- [11] Han van Ruler, Who was this Erasmus Anyway?, Studium Generale @ youtube

- [12] Smith, Preserved (1928). “Erasmus: A Study of His Life Ideals And Place in History”. Harper & Brothers.

- [13] Emerton, Ephraim (1899). Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- [14] Timeline for Erasmus of Rotterdam, via Wikidata

Related Articles in the Blog:

Pingback: CLAY JENKINSON: Future In Context — Gutenberg To Zuckerberg: A Tale Of Two Revolutions – UNHERALDED.FISH

Pingback: Sunday Reading – 02/21/2021 | Romick in Oakley