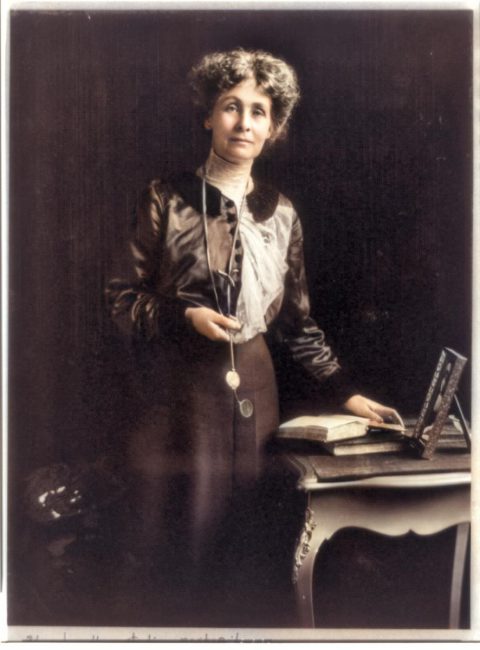

Emmeline Pankhurst is arrested by police outside

Buckingham Palace, in May 1914

On July 14, 1858, British political activist and leader of the British suffragette movement Emmeline Pankhurst was born, who helped women win the right to vote. Emmeline Pankhurst was named one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century by the Time magazine.

What a pity she wasn’t born a lad

Born in Manchester as first of nine children, Emmeline Pankhurst was the daughter of Robert Goulden, who came from a family with radical political beliefs and took part in the campaigns against slavery and the Corn Laws, and Sophia Crane, a passionate feminist who started taking her daughter to women’s suffrage meetings already in the early 1870s. Although her parents encouraged her to prepare herself for life as a wife and mother, she attended the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Emmeline, who was an extremely intelligent child, later recalled that when she was young she overheard her father sometimes saying, “What a pity she wasn’t born a lad.“

“Human life for us is sacred, but we say if any life is to be sacrificed it shall be ours; we won’t do it ourselves, but we will put the enemy in the position where they will have to choose between giving us freedom or giving us death.”

— Emmeline Pankhurst, From Freedom or Death (1913) [3]

Marriage Arrangements

In 1879, Emmeline married Richard Pankhurst, a lawyer and supporter of the women’s suffrage movement. He was the author of the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, which allowed women to keep earnings or property acquired before and after marriage. Richard, 44 years old when they met, had earlier resolved to remain a bachelor in order to better serve the public [2]. Although their mutual affection was powerful, Emmeline suggested to Richard that they avoid the legal formalities of marriage by entering into a free union; he objected on the grounds that she would be excluded from political life as an unmarried woman.

Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928)

The Women’s Franchise League

In 1889, Emmeline founded the Women’s Franchise League, which fought to allow married women to vote in local elections. In 1893 Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst formed a branch of the new Independent Labour Party (ILP) and in the 1895 General Election, Pankhurst stood as the ILP candidate for Gorton, an industrial suburb of Manchester, but was defeated. In 1894 Emmeline Pankhurst became a Poor Law Guardian, a position which involved regular visits to the Chorlton Workhouse and she was deeply shocked by the misery and suffering of the inmates. She became particularly concerned about the way women were treated and it reinforced her belief that women’s suffrage was the only way these problems would be solved. Emmeline began organizing Sunday open-air meetings in the local park. The local authority declared that these meetings were illegal and speakers began to be arrested and imprisoned.

“I thought I had been a suffragist before I became a Poor Law Guardian, but now I began to think about the vote in women’s hands not only as a right but as a desperate necessity.”

— Emmeline Pankhurst

Women’s Social and Political Union

After Richard’s death in 1898, which was a great shock for Emmiline, she threw herself even more into the women’s suffrage movement. In October 1903, she helped found the more militant Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) – an organisation that gained much notoriety for its activities and whose members were the first to be christened ‘suffragettes’. Emmeline’s daughters Christabel and Sylvia were both active in the cause. British politicians, press and public were astonished by the demonstrations, window smashing, arson and hunger strikes of the suffragettes. In 1913, WSPU member Emily Davison was killed when she threw herself under the king’s horse at the Derby as a protest at the government’s continued failure to grant women the right to vote.[2]

“The condition of our sex is so deplorable that it is our duty to break the law in order to call attention to the reasons why we do.”

— Emmeline Pankhurst

Hunger-Strike

In 1913 the WSPU increased its campaign to destroy public and private property. The women responsible were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Determined to avoid these women becoming martyrs, the government introduced the Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge of Ill Health Act. Suffragettes were now allowed to go on hunger strike but as soon as they became ill they were released. Once the women had recovered, the police re-arrested them and returned them to prison where they completed their sentences. This successful means of dealing with hunger strikes became known as the Cat and Mouse Act. When, in August 1914, every other issue was swamped by the outbreak of war in Europe, Pankhurst came to the quick conclusion that the defeat of republican France would not serve the women’s cause or anybody else’s and Emmeline turned her energies to supporting the war effort.[4]

Equal Voting Rights for Women

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act gave voting rights to women over 30. In 1926, Emmeline surprised many by joining the Conservative party, and two years later running for Parliament as a Conservative candidate. But, after the Russian revolution in October 1918, Emmeline despite her earlier political experiences and sympathy with the poor was increasingly concerned by communism. Emmeline Pankhurst died on 14 June 1928, at the age of 69, shortly after women were granted equal voting rights with men.

Emmeline Pankhurst, Great Women in History, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Emmeline Pankhurst at BBC History

- [2] Emmeline Pankhurst at Biographies Online

- [3] Michael Foot: The stronger vessel, in the Guardian, August 3, 2002

- [4] Mikhail Bakunin and the Anarchism, SciHi Blog

- [5] Karl Marx and the Capital, SciHi Blog

- [6] Emmeline Pankhurst at Wikidata

- [7] Emmeline Pankhurst, Freedom or death, 1913 speech in the US, via Wikisource

- [8] Works by or about Emmeline Pankhurst at Internet Archive

- [9] Emmeline Pankhurst, Great Women in History, @ youtube

- [10] Riddell, Fern (6 February 2018). “Suffragettes, violence and militancy”. British Library

- [11] Fulford, Roger. Votes for Women: The Story of a Struggle. London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1957.

- [12] “PANKHURST, Emmeline (1858–1928) & PANKHURST, Dame Christabel (1880–1958)”. English Heritage. 21 December 1908.

- [13] Kamm, Josephine. The Story of Mrs Pankhurst. London: Methuen, 1961.

- [14] Timeline of Feminism, via DBpedia and Wikidata