Pedro Calderón de la Barca (17. Januar 1600 – 25. Mai 1681)

On January 17, 1600, Spanish poet and playwright of the Spanish Golden Age Pedro Calderón de la Barca was born. His work being regarded as the culmination of the Spanish Baroque theatre. As such, he is regarded as one of Spain’s foremost dramatists and one of the finest playwrights of world literature.

|

|

– Calderón de la Barca, La Vida es sueño (Life Is a Dream), 1636

Calderón’s Early Years

Calderón came from a Spanish noble family. His father held the office of treasurer at the Spanish court. However, he lost his parents relatively early: his mother, who came from the Spanish Netherlands in Mons, died in 1610, and his father died only five years later. Calderón attended the Jesuit College in Madrid from 1609 to 1614. He should become a priest, but already at this time he began to occupy himself with literature. He continued his education by studying law at the University of Alcalá de Henares and the University of Salamanca, but broke it off in 1620 to become a soldier in the navy. From 1620 to 1622 he successfully participated in a literary competition held in Madrid in honour of St. Isidore. Lope de Vega, who was the organiser of this competition, wrote: “A prize was awarded to Don Pedro Calderón, who at his age won laurels that time only gave grey hair“.[1]

In the Foot Steps of Lope de Vega

According to his biographer Diego Juan de Vera Tassis y Villarroel, Calderon is said to have served in the Spanish army from 1625 to 1635 and to have been a soldier in Flanders and Italy. However, there are documents that prove that Calderón actually lived in Madrid during this time. After the death of Lope de Vega in 1635 he took over his position as court dramatist. He was recognized as the best playwright of his time. A volume of his plays, published by his brother José in 1636, contained the works celebrated at the time, such as La Vida es sueño (Life is a Dream), El Purgatorio de San Patricio (The Purgatory of Saint Patricius), La Devoción de la Cruz, La Dama duende (Lady Goblin) and Peor está que estaba. From 1636 to 1637 Calderón was made a Knight of the Order of Santiago by Philip IV, who had already commissioned a series of plays for the Royal Theatre in Buen Retiro. He was as popular with the audience as Lope de Vega was at the height of his fame.

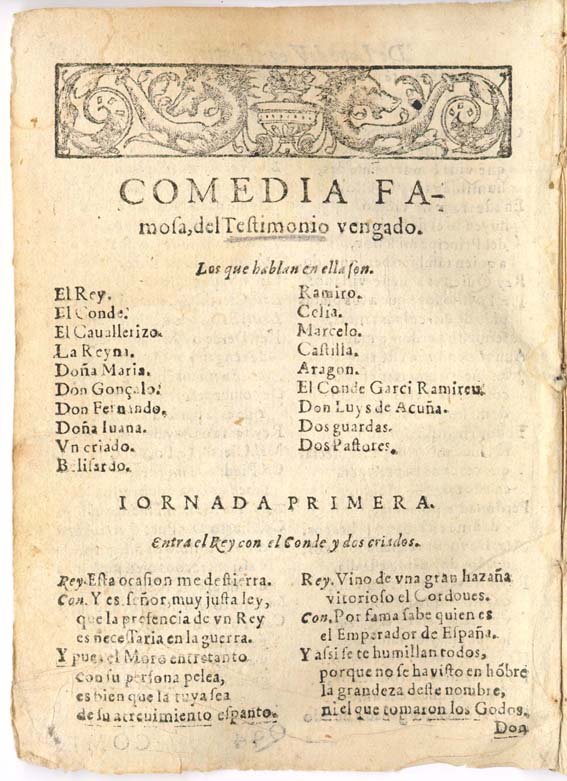

Title page from a comedy by Spanish playwright Lope de Vega.

In the Army

Despite this position, he joined a unit of mounted cuirassiers on 28 May 1640, which was put together by the Spanish general Olivares. He took part in the Spanish campaign against the renegade Catalonia and distinguished himself above all by his nobility in the city of Tarragona. When his health was seriously affected (some biographers speak of a wound), he left the Spanish army in November 1642. Three years later he received a pension for his services.

Ordained Priest and Spanish Inquisition

The story of his life during the next few years is largely in the dark. It seems that, due to the death of his wife, he had to struggle with serious personal problems in 1648 and 1649 and turned again to the church. In 1650 he joined the Franciscan Order. In 1651 he was ordained a priest and became parish priest of a parish in the town of San Salvador in Madrid. His intention was never again to write a play for the theatre. He stuck to it until he became chaplain in Toledo in 1653. After that he began to spend much of his time writing Autos sacramentales. They were performed with great effort on Corpus Christi and in the weeks that followed. In 1662 two of Calderón’s pieces (Las órdenes militares and Mística y real Babilonia) became the subject of an investigation by the Spanish Inquisition. It censored the first of the two plays and confiscated the manuscripts. In 1671, however, the sentence was reversed.

Final Years

“But whether it be dream or truth, to do well is what matters. If it be truth, for truth’s sake. If not, then to gain friends for the time when we awaken.”

– Calderón de la Barca, La Vida es sueño (Life Is a Dream), 1636

In 1663 the Spanish king Philip IV appointed Calderón as court chaplain. He retained this office even after Charles II took power in 1665. At the age of 81 he wrote his last secular play, Hado y Divisa de Leonido y Marfisa, in honour of the marriage of Charles II to Marie-Louise of Bourbon. Despite his position at court he spent his last years in poverty.

Calderon`s Theatre

Calderón initiated what has been called the second cycle of Spanish Golden Age theatre. Whereas his predecessor, Lope de Vega, pioneered the dramatic forms and genres of Spanish Golden Age theatre, Calderón polished and perfected them. Whereas Lope’s strength lay in the spontaneity and naturalness of his work, Calderón’s strength lay in his capacity for poetic beauty, dramatic structure and philosophical depth. Calderón was a perfectionist who often revisited and reworked his plays, even long after they were first performed. This perfectionism was not just limited to his own work: several of his plays rework existing plays or scenes by other dramatists, improving their depth, complexity, and unity. Calderón excelled above all others in the genre of the “auto sacramental”, in which he showed a seemingly inexhaustible capacity to giving new dramatic forms to a given set of theological and philosophical constructs. Calderón wrote 120 “comedias”, 80 “autos sacramentales” and 20 short comedic works called entremeses.

Legacy

As Johann Wolfgang von Goethe notes,[2] Calderón tended to write his plays taking special care of their dramatic structure. He therefore usually reduced the number of scenes in his plays as compared to those of Lope de Vega, so as to avoid any superfluity and present only those scenes essential to the play, also reducing the number of different metres in his plays for the sake of gaining a greater stylistic uniformity. Although his poetry and plays leaned towards culteranismo, he usually reduced the level and obscurity of that style by avoiding metaphors and references away from those that uneducated viewers could understand. Although his fame dwindled during the 18th century, he was rediscovered in the early 19th century by the German Romantics.

The History of Spanish Literature, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Lope de Vega and the Spanish Golden Age of Literature, SciHi Blog

- [2] The Life and Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, SciHi Blog

- [3] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Calderón de la Barca, Pedro“. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [4] Works by or about Pedro Calderón de la Barca at Internet Archive

- [5] “Calderón de la Barca”. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2014.

- [6] Calderón de la Barca at Wikidata

- [7] The History of Spanish Literature, History of Spain @ youtube

- [8]Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. Life’s a Dream: A Prose Translation. Trans. and ed. Michael Kidd (Boulder, Colorado, 2004).

- [9] Timeline for Calderon de la Barca, via Wikidata