Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571)

On November 3, 1500, Italian goldsmith, sculptor, draftsman, soldier, musician, and artist Benvenuto Cellini was born. Cellini was one of the most important artists of Mannerism. He is remembered for his skill in making pieces such as the Cellini Salt Cellar and Perseus with the Head of Medusa.

Cellini’s Family and Youth

Benvenuto Cellini was born in Florence, the son of the architect and musician Giovanni Cellini and his wife Maria Elisabetta di Stefano Granacci. His father was an architect of defensive structures in the service of the Medici. He also worked in the arts and crafts and made musical instruments. He wanted Benvenuto to become a musician, but at the age of 14 he decided to become a goldsmith.Benvenuto had difficulty getting his father to teach him to Michelangelo da Viviano, the father of his later archrival Baccio Bandinelli. But when his father soon took him back, he broke out and went to Antonio di Sandro’s workshop, where he made rapid progress. In 1516 he was banished from Florence for six months for a brawl with master Francesco Castoro in Siena. At the behest of Giulio de’ Medici, later Pope Clement VII, he was allowed to return. In Bologna he worked for a short time with Master Ercole, then for the miniaturist Scipio Cavaletti.

Becoming a Goldsmith and Engraver

The music making that he had continued until then for the sake of his father was now completely repugnant to him; it came to a quarrel with his father, as a result of which he left Florence again and went to Rome. Meanwhile, disputes with colleagues increasingly resulted in brawls, as a result of which Cellini – disguised as a monk – had to flee Florence. In 1523 he went to Rome again, where his patron Giulio de’ Medici was enthroned as Pope Clement VII. In the workshop of the Milanese Giovanpiero della Tacca, Cellini began a “large kettle” designed by the painter Gioanfrancesco Penni for the Bishop of Salamanca. However, the speedy execution of the commission was hindered after Cellini, moved by his father, who had appeared to him in a dream, begging and threatening him, had entered papal service as a musician. Angered by the delay in delivery, the bishop refused to pay as agreed upon receipt of the work. After Cellini had succeeded in getting himself back into possession of the work, he defended the renewed publication by force of arms against the bishop’s servants. This coup made Cellini widely known to Roman society. The orders he received enabled him to open his first workshop.

The Siege of Rome and the Plagues

Like many Romans, Cellini avoided the plague that broke out in Rome in 1525 by staying in the country. He bought up the antique medals, gems and precious stones found relatively frequently by the peasants while working in the fields for a little in order to sell them, back in Rome, profitably to art-loving cardinals. During the siege of Rome in 1527, as a faithful follower of the Medici, he also took up arms and took over the supervision of some guns at the Angel Castle. On behalf of the pope he destroyed without any scruples a number of valuable art objects in order not to let them fall into the hands of the besiegers. He embezzled part of the treasure. After the end of the siege, he returned to Florence as Capitano, and soon thereafter travelled on to Mantua, where he worked for the Duke’s goldsmith Niccolo of Milan for a short time.

A First Murder

On behalf of Girolamo Mazzeti he worked out a “gold medal to wear on the hat, whereupon a Hercules tears the lion’s throat open”. This work won the applause of Michelangelo Buonarroti. This praise of the then already “deified” artist increased his need for recognition enormously and his desire for larger works grew. From Florence Cellini went back to Rome and worked there temporarily for the goldsmith Raffaelo del Moro. Thanks to a favourable order situation, he was soon able to open his own workshop again. His brother Francesco, who was a soldier in Rome, was shot there in a scuffle on the open road. Cellini’s subsequent murder of his brother’s murder was punished by the Pope “with a grim sideways glance”. After a night-time burglary in his workshop, in which a number of pieces of jewellery and mint stamps were stolen, counterfeit coins struck with his stamp came into circulation. Cellini was suspected of counterfeiting, against which the Pope defended him. After the discovery of the perpetrators, the Pope saw his confidence in him strengthened and gave him the lucrative position of a papal personal trotant. This hierarchical ascent led Cellini to a series of arrogance and quarrels until he finally faced a superiority of enemies.

More Murders

Pope Clement VII died in 1534, followed by Paul III of the House of Farnese. Cellini Pompeo killed de´ Capianeis, the instigator of his persecution. Instead of being punished by the Pope, he received a carte blanche from him. Secured by this, he first worked the stamps for the issue of new scudi on the occasion of the election of Paul III. The family of the murdered Pompeo, meanwhile, searched for revenge. Cellini however escaped the hired murderers to Florence. Another Pope’s carte blanche enabled him to return to Rome. There he was attacked one night, saved not least by the carte blanche. Then he fell so seriously ill that his death was expected. Although sonnets had already been written about his death, he recovered miraculously. According to Cellini, he committed three murders. The third happened to a postal worker in Siena. He was tried several times in his life. Once he was sentenced to death. In addition to bodily injury, Cellini was also tried several times for theft and sexual practices considered abnormal.

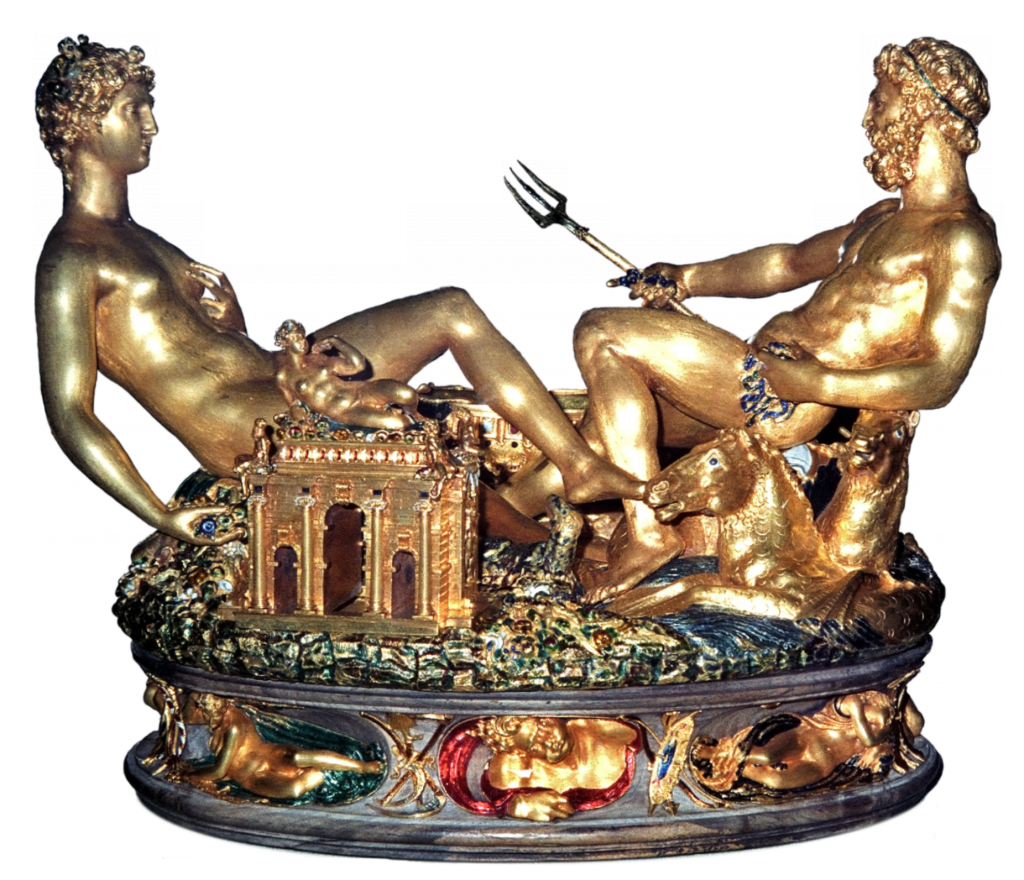

Saliera (Salt Cellar) von Cellini (Paris, 1540-1543 gold, partly enamelled; pedestal: ebony), today in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Imprisonment and Working to France

In Rome he was arrested on the basis of a rumour launched by his enemies that he had stolen precious stones when melting down the papal treasure. For two years he remained imprisoned without charge in the Angel Castle. An escape attempt led to even stricter imprisonment. Attempts were made to poison him. It was only after the intervention of the Cardinal of Ferrara, Ippolito d’Este, that Cellini was released; he was commissioned to deliver the invitation to the French court of Francis I to him. In Fontainebleau he met King Francis I, who promised him great commissions. The king commissioned him to make the salt cask, whose model Cellini had already made for Hippolyt d’Este in Rome. The King’s protection also led to a flood of orders for the workshop from outside. Numerous works in precious metals and bronze were created.

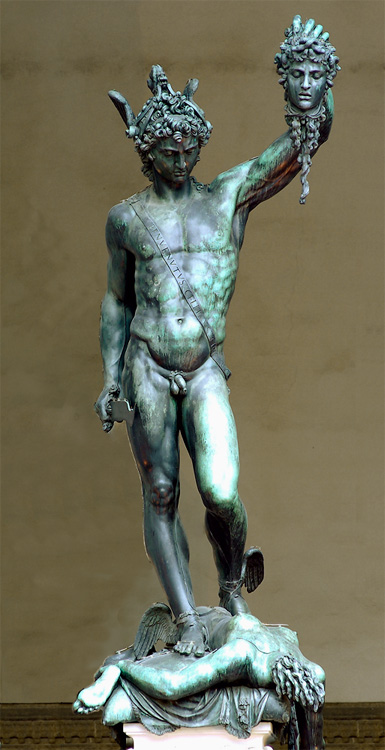

Perseus with the Head of Medusa, Bronze monumental de Benvenuto Cellini, 1545 – 1554 – Florence – Loggia del Lanzi.

Perseus and the Head of Medusa

In 1545 Cellini requested leave, which was finally granted to him after initial refusals. He travelled to Italy. In Florence he approached Duke Cosimo, who asked him to enter his services. The Perseus sculpture that Cellini had promised him, hoping to compete with his great models Michelangelo and Donatello, attracted him so much that he accepted the offer. Franz I then accused him of ingratitude, demanded an exact account and waived his right to return. In 1554 Perseus was placed in the Loggia dei Lanzi, where it is still today. Since Cellini did not want to leave the four figures for the Perseus pedestal to the Duchess, who desired them for her private collection, he had, however, also largely gambled away his loan in the Duke’s family, so that no larger commissions were to be expected from there. Perseus was Cellini’s greatest work. Still in the year of his unveiling, Cellini was solemnly accepted into the Florentine aristocracy, despite the fact that at that time he had sunk deeply in the duke’s respect, but without falling completely out of favour.

Last Years

The eternal arguments and the ultimately unfulfilled craving for recognition showed ever clearer traces with Cellini. So he decided to change to the clergy and also took the tonsure in 1558. However, this did not change much about his quarrelsomeness. The last few years were cloudy for him. He had misfortune with those who administered his money and became involved in lawsuits; since he worked little or nothing at all, there was no income. Already in 1560 he was released from his vows and married in 1563 his housekeeper Piera di Salvadore Parigi, with whom he already had an illegitimate son, but who had already died in 1559. After the last years of great financial difficulties, from which numerous letters of petition have been received, Cellini died on 13 February 1571 in Florence from a pleurisy, from which he had suffered for some time.

Rick Steves, Art II: Renaissance & Baroque 1400–1800 [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Michelangelo Buonarotti – the Renaissance Artist, SciHi Blog

- [2] Not Simply a Piece of Marble – Michelangelo’s David, SciHi Blog

- [3] Works by or about Benvenuto Cellini at Internet Archive

- [4] Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, Symonds translation at Project Gutenberg

- [5] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Cellini, Benvenuto“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 604–606

- [6] Benvenuto Cellini at Wikidata

- [7] Rick Steves, Art II: Renaissance & Baroque 1400–1800, Rick Steves Travel Talk @ youtube

- [8] Timeline for Benvenuto Cellini, via Wikidata