Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945)

On March 25, 1881, Hungarian composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist Bela Bartok was born. Bartok is considered one of the most important representatives of modernism. Through his collection and analytical study of folk music, he was one of the founders of comparative musicology, which later became ethnomusicology.

“Our peasant music, naturally, is invariably tonal, if not always in the sense that the inflexible major and minor system is tonal. (An “atonal” folk-music, in my opinion, is unthinkable.) Since we depend upon a tonal basis of this kind in our creative work, it is quite self-evident that our works are quite pronouncedly tonal in type. I must admit, however, that there was a time when I thought I was approaching a species of twelve-tone music. Yet even in works of that period the absolute tonal foundation is unmistakable.”

– Bela Bartok, “The Folk Songs of Hungary” in Pro Musica VII (October 1928)

Early Years

Bartók spent his childhood in the Kingdom of Hungary of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was partitioned by the Treaty of Trianon after the First World War. Bartók’s father, Béla Bartók the Elder (1855-1888), was the director of an agricultural school and played the cello in an amateur orchestra. The mother, Paula Bartók, née Voit (1857-1939), was a teacher. After his father’s death in 1888, Bartók lived with his mother in Nagyszőllős (now Vynohradiv, Ukraine) and Beszterce (Bistritz) before moving to Pozsony (Bratislava, Slovakia) for high school. Bartók’s exceptional musical talent and absolute ear were noticed at a very early age. Bartók performed in public for the first time at the age of eleven. Early on, however, he also noticed his tendency to all kinds of illnesses, which was to accompany him throughout his life and was also responsible for his early death.

Peasant Music

Later Bartók began to study piano under the Liszt pupil István Thomán and composition under Hans Koessler. Koessler’s teaching, however, soon struck him as too conservative and scholarly. Around 1905 he met Zoltán Kodály at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest. He introduced Bartók to the systematic study of folk music. Until then, he had associated Hungarian folk music primarily with the music performed by Roma in the cities, such as Franz Liszt [1] in the Hungarian Rhapsodies or Johannes Brahms in the Hungarian Dances, which had given these works international popularity.

It soon turned out that these were rather romantically imitated, newly composed art songs. Bartók, on the other hand, was looking for the original music of the rural population, which he himself described as “peasant music.” As early as 1903, Bartók had written an extensive orchestral work called Kossuth. Here, the popular, romantic Hungarian style is still processed, which was also considered “original Hungarian” by Bartók at the time. This stems from the fact that the composer felt a strong obligation to write nationally influenced Hungarian music in his early work. Bartók, like many other artists throughout Europe, was searching for a national style in music. This was to draw from the old, which was yet to be discovered, and at the same time create something new.

1st Violin Concerto and Stefi Geyer

The music of Richard Strauss, whom Bartók met in 1902 at the Hungarian premiere of Also sprach Zarathustra in Budapest, initially had a great influence on his work in terms of orchestral music. The romantic exuberance, however, soon seemed to him to be no longer in keeping with the times. In contrast, the music of Franz Liszt left a more lasting impression.[1] Bartók was an excellent pianist and initially aspired to a career as such. However, as early as 1907 he received a position as professor from the Royal Academy. The years 1907/08 saw the composition of one of Bartók’s most personal works, the 1st Violin Concerto. At that time he had fallen in love with the 20-year-old violinist Stefi Geyer. He dedicated his first violin concerto to her and gave her the score. Geyer never played the concerto in public and kept the manuscript under lock and key for almost half a century. Bartók’s Violin Concerto was finally premiered in 1958.

Bluebeard’s Castle

In 1909 Bartók and Márta Ziegler were married. Their son Béla junior was born in 1910. In 1911 Bartók wrote his only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle, which he dedicated to his wife. For service in the k.u.k. Bartók was unfit for service in the Wehrmacht. However, from 1915 to 1918, together with the conductor and composer Bernhard Paumgartner, he was responsible, among other things, for collecting soldiers’ songs in the music department of the war press quarters of the Imperial and Royal War Ministry. In 1919 Bartók joined the Music Directorate of the Hungarian Civic Republic, which also included Zoltán Kodály.

Hungarian Folk Songs

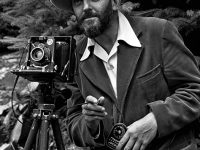

Out of his disappointment with the Fine Arts Commission, he composed less over the next two or three years and concentrated more on building a collection of Hungarian folk songs. The main result of this was The Hungarian Folk Song in 1922/1923. This is not, however, a mere anthology of Hungarian folk melodies and texts, but a scientifically oriented attempt to systematize melodies according to type, approximate age, and regional occurrence. To this end, Bartók drew on an enormous treasure trove of some 3000 melodies and texts, most of which he himself, but also through other researchers, listened to directly from the rural population. During these field explorations, the melodies were either phonographed and later transcribed or put into musical notation directly on site. The collection of folk songs and the transcription of his phonographic recordings was a task of utmost importance for Bartók.

Béla Bartók using a phonograph to record Slovak folk songs sung by peasants in Zobordarázs (Slovak: Dražovce, today part of Nitra, Slovakia)

Ethnomusicology

To this end, Bartók drew on an enormous treasure trove of some 3000 melodies and texts, most of which he himself, but also through other researchers, listened to directly from the rural population. During these field explorations, the melodies were either phonographed and later transcribed or put into musical notation directly on site. The collection of folk songs and the transcription of his phonographic recordings was a task of utmost importance for Bartók. Apart from the territory of what was then Hungary, including large areas that since 1945 have belonged to Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine, or even Serbia, Bartók’s research trips continued to the Balkans, Russia, and Turkey and North Africa. The ballet The Wooden Prince (1914-1916) and his 2nd String Quartet (1915-1917) emerged from this phase of his artistic work. Bartók achieved world fame through The Wooden Prince.

Emigration

Bartók then worked on another ballet, The Miraculous Mandarin, which parallels Igor Stravinsky in its expressive tonal language. Due to the outbreak of World War II and the successively worsening political situation in Europe, Bartók was inclined to leave Hungary. He strongly condemned National Socialism. In August 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war, he stayed in Saanen, Switzerland, as the guest of Paul Sacher, on whose commission he wrote his last string quartet and a divertimento for string orchestra. Having already sent his manuscripts to the United States, he emigrated to America with his wife. Bartók felt alienated in the U.S. and found it difficult to continue composing. He was also hardly known in the USA. There was little interest in his works. At Harvard University, Bartók gave several lectures, including one on composing in the 20th century. Nevertheless, the family’s financial situation was in a precarious state, as was Bartók’s health. The diagnosis of his progressive leukemia disease, which among other things led to constant fever, was concealed from him by his doctors until the end, although he suspected the seriousness of his condition.

Then End

Bartók thus found some strength to compose once again and then began his cool and almost neo-classical 3rd Piano Concerto, the Viola Concerto and his 7th String Quartet. The works, however, turned into a race with death. Bartók’s apartment during the last years of his life was in Manhattan, in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood at 309 West 57th Street. He died there of leukemia on September 26, 1945 at age 54.

Legacy

Bartók is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century, without being classified as part of the musical avant-garde. His musical language incorporates Hungarian folk music, but combines it with achievements of musical modernism. For example, Bartók uses all twelve tones while maintaining a modal character. Especially in the field of chamber music, Bartók’s compositions are among the best in 20th-century music. A few years after Bartók’s death, the film industry began to take an interest in his works, and so, from the 1950s on, some of his pieces were repeatedly used as film music for cinema and TV productions, for example the 3rd part of the music for stringed instruments, percussion and celesta in Stanley Kubrick‘s Shining (1980).[2]

Michael Parloff, Lecture on Bartók’s Quest for Musical Authenticity (Music@Menlo), [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Franz Liszt – Rockstar of the 19th Century, SciHi Blog

- [2] Breaking New Grounds in Cinematography – Stanley Kubrick, SciHi Blog

- [3] Babbitt, Milton. 1949. “The String Quartets of Bartók“. Musical Quarterly 35 (July): 377–85. Reprinted in The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt, edited by Stephen Peles, with Stephen Dembski, Andrew Mead, and Joseph N. Straus. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- [4] Stevens, Halsey. 2018. “Béla Bartók: Hungarian Composer“. Encyclopædia Britannica online

- [5] Nelson, David Taylor (2012). “Béla Bartók: The Father of Ethnomusicology”, Musical Offerings: Vol. 3: No. 2, Article 2

- [6] “Bela Bartok, Composer, Dies in New York”. Musical America. 65 (13): 41. October 1945.

- [7] Works by or about Béla Bartók at Internet Archive

- [8] Michael Parloff, Lecture on Bartók’s Quest for Musical Authenticity (Music@Menlo), Michael Parloff @ youtube

- [9] Interactive scores of Bartók’s works for piano with Sir András Schiff.

- [10] Bela Bartok at Wikidata

- [11] Timeline for Bela Bartok, via Wikidata