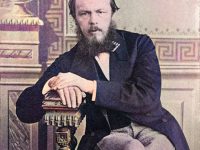

Anton Chekov (1860-1904), Portrait by Osip Braz (1898)

On July 15, 1904, Russian playwright and short-story writer Anton Chekov passed away. Chekov is considered to be among the greatest writers of short fiction in history. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his best short stories are held in high esteem by writers and critics. Chekhov was working as a medical doctor throughout most of his literary career: “Medicine is my lawful wife“, he once said, “and literature is my mistress.”

“When a person is born, he can embark on only one of three roads of life: if you go right, the wolves will eat you; if you go left, you’ll eat the wolves; if you go straight, you’ll eat yourself.”

— Anton Chekov, Fatherlessness or Platonov, Act I, sc. xiv (1878)

Youth and Education

Anton Chekhov was born on 29 January 1860 in the southern Russian port city of Taganrog on the Azov Sea. His father, Pavel Yegorovich Chekhov, was the son of a former agrarian farmer from the Voronezh Province, and ran a small cheap goods shop in Taganrog as a merchant. Chekhov’s mother, Yevgenia Yakovlevna Chekhova (née Morozova), also came from a former ancestral farming family. The couple raised a total of six children. Despite their depressing financial situation, Chekhov’s parents attached importance to providing their children with a solid general education: At the age of eight, Anton was introduced to the preparatory class of the Second Taganrog Boys’ High School, which he attended from 1869 until his graduation in 1879.

A Strong Sense of Humour

Even as a high school student, Anton Chekhov, who was otherwise regarded as reserved and reserved, showed a strong sense of humor and a great deal of interest in acting and literature. In school, for example, he earned the reputation of a rogue for his satirical comments and bad habits and his ability to call teachers by humorous nicknames. After graduating from high school in 1879, Chekhov was granted a scholarship of 25 rubles a month by the city administration of Taganrog and then travelled to Moscow with two schoolmates to study medicine – as he had planned long before.

A Medical Degree

Chekhov’s career at Moscow’s Lomonosov University, where he enrolled shortly after his arrival in Moscow, lasted from 1879 until his graduation in the summer of 1884, when the seven-member Chekhov family moved house several times and had to be satisfied with extremely cramped living conditions, especially in the first months, which caused Anton immense difficulties in preparing for the examination. These were exacerbated by the fact that from the early years of his studies he devoted himself to writing, which proved to be an important source of income in view of the poverty in which the family had to live. Although he passed all the exams properly and obtained a medical degree within the specified five years, Chekhov was considered a rather average, unattractive student.

First Publications

Chekhov himself later described several times in his letters the period between 1878 and 1880 as the beginning of his actual literary activity. The first Czechovian publications still preserved today date from 1880, when after several unsuccessful attempts Anton finally succeeded in publishing ten humorous short stories and miniatures in the St. Petersburg journal Strekosa (in English “Firefly“). Similar publications followed in 1881 and 1882 in numerous more or less well-known humour and satire magazines, including Budilnik (“The Alarm Clock“), Sritel (“Spectator“), Moskva (“Moscow“) and Svet i teni (“Light and Shadow“).

“While you’re playing cards with a regular guy or having a bite to eat with him, he seems a peaceable, good-humoured and not entirely dense person. But just begin a conversation with him about something inedible, politics or science, for instance, and he ends up in a deadend or starts in on such an obtuse and base philosophy that you can only wave your hand and leave.”

— Anton Chekov, Ionych (1898)

Famous Short Stories

Until his admission as a doctor in 1884, he succeeded in publishing a total of more than 200 stories, feuilletons and humoresques in various magazines under several pseudonyms. Some of the stories written during this period are still among his most famous works today, such as the satirical short stories Death of a Government Clerk, Albion’s daughters or A Chamaeleon (1884).

Tuberculosis

However, it was also his work as a doctor that Chekhov was able to provide much material for his narratives, and especially in the second half of the 1880s he wrote particularly intensively: Thus in 1885 alone a total of 133 texts were printed by him, in 1886 there were 112 and in 1887 at least 64. This only began to change after Chekhov, who has since enjoyed a certain popularity in literary circles. In 1884 and 1885, Chekhov found himself coughing blood, and in 1886 the attacks worsened, but he would not admit his tuberculosis to his family or his friends. He continued writing for weekly periodicals, earning enough money to move the family into progressively better accommodations.

Literary and Popular Attention

Early in 1886 he was invited to write for one of the most popular papers in St. Petersburg, Novoye Vremya (New Times). Before long, Chekhov was attracting literary as well as popular attention. The sixty-four-year-old Dmitry Grigorovich, a celebrated Russian writer of the day, wrote to Chekhov after reading his short story “The Huntsman” that “You have real talent, a talent that places you in the front rank among writers in the new generation.” In 1887, exhausted from overwork and ill health, Chekhov took a trip to Ukraine, which reawakened him to the beauty of the steppe. On his return, he began the novella-length short story “The Steppe,” which he called “something rather odd and much too original,” and which was eventually published in Severny Vestnik (The Northern Herald).

Famous Plays

In 1887, a theatre manager named Korsh commissioned Chekhov to write a play, the result being Ivanov, written in a fortnight. Though Chekhov found the experience “sickening” and painted a comic portrait of the chaotic production in a letter to his brother Alexander, the play was a hit and was praised, to Chekhov’s bemusement, as a work of originality. Although Chekhov did not fully realise it at the time, Chekhov’s plays, such as The Seagull (1895), Uncle Vanya (1897), The Three Sisters (1900), and The Cherry Orchard (1903) served as a revolutionary backbone to what is common sense to the medium of acting to this day: an effort to recreate and express the “realism” of how people truly act and speak with each other and translating it to the stage to manifest the human condition as accurately as possible in hopes to make the audience reflect upon their own definition of what it means to be human, warts and all.

Winter at the Crimean Sea

In March 1897 Chekhov suffered a particularly severe lung hemorrhage in Moscow, after which he was admitted to hospital for several weeks. It was also the first time ever that Chekhov had been examined for his tuberculosis disease; before, although he himself was a doctor, he had always refused to be treated medically. Some doctors now recommended that he stay in the winter months on the Black Sea peninsula of Crimea, known for its mild climate, or even in other European countries. Chekhov followed this advice and traveled to the French Mediterranean coast for several months in the autumn of 1897. In September 1898 he drove to Yalta in Crimea and a month later bought a plot of land for a new property.

“Between “there is a God” and “there is no God” lies a whole vast tract, which the really wise man crosses with great effort. A Russian knows one or other of these two extremes, and the middle tract between them does not interest him; and therefore he usually knows nothing, or very little.”

— Anton Chekov, Diary, 1897

Meeting Maxim Gorki

Even though Chekhov met a large number of contemporary authors in Yalta with whom he later became friends – among them the revolutionary writer Maxim Gorki [6] – and he also stood up for charity there, he increasingly lamented the barren and provincial atmosphere of Yalta, which could not be compared with the social and cultural life of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Further Treatment and Death

At the beginning of June 1904 Chekhov and his wife went to Germany for another treatment. After a temporary improvement in his well-being, Chekhov suffered several heart failure attacks in mid-July, the last of which led to his death on the night of July 15.

Chekov’s Legacy

In the course of his almost twenty-five-year career as a writer, Chekhov has published several hundred stories, short stories and feature pages, as well as over a dozen plays. Many of the early works from the early 1880s – mainly short stories, jocular miniatures, parodies and the like – are characterized by Chekhov’s characteristic witty style, while most of his mature works can be attributed to realism, to which Chekhov’s scientific knowledge from his studies and his medical experience as a village doctor contributed significantly. Most of his important stories revolve around the life of the petty bourgeoisie in Russia at the end of the 19th century, about sin, evil, the decline of spiritual life and society. The plot, which often has an open end, is typically integrated in a central or southern Russian landscape or in a small-town, provincial environment. Many such stories read as deep, tired sighs.

Chekov’s Famous Plays

In his plays – almost all of which were written after 1885, when Chekhov’s literary style had long since matured beyond his purely humorous component – Chekhov largely retained the method of objective description developed in the stories. In addition, the pieces are distinguished by the tragicomic view of the banality of provincial life and the transience of the Russian small nobility. Most of the people acting there are decent and sensitive; they dream of improving their lives, but mostly in vain, because of the feeling of helplessness and uselessness, the exaggerated self-pity and the resulting lack of energy and willpower.

“Dear and most respected bookcase! I welcome your existence, which has for over one hundred years been devoted to the radiant ideals of goodness and justice.”

— Anton Chekov, The Cherry Orchard, 1904, Act I

Chekhov, who never wrote a longer novel (even though he repeatedly expressed this intention at the end of the 1880s), exerted an immense influence on the formation of the modern novella and the play in his concise, restrained and value-free narrative style. Even today Chekhov is regarded as an early master of the short story.

Theatre and The Family, Anton Chekhov ‘The Cherry Orchard’ – Professor Belinda Jack (novideo), [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Anton Chekhov at Encyclopædia Britannica

- [2] Petri Liukkonen. “Anton Chekhov”. Books and Writers

- [3] Works by or about Anton Chekhov at Internet Archive

- [4] Texts by Anton Chekov at Wikisource

- [5] Anton Chekov at Wikidata

- [6] Maxim Gorky and the Socialist Realism, SciHi Blog

- [7] Theatre and The Family, Anton Chekhov ‘The Cherry Orchard’ – Professor Belinda Jack (novideo), Gresham College @ youtube

- [8] Rayfield, Donald (1997). Anton Chekhov: A Life. London: HarperCollins.

- [9] Simmons, Ernest Joseph (1970) [1962]. Chekhov: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- [10] Timeline for Anton Chekov, via Wikidata

Pingback: Who wants to live forever? - Adam Mazek Photography