Amelia Edwards (1831-1892)

On June 7, 1831, English novelist, journalist, traveller and Egyptologist Amelia B. Edwards was born. Her account of her travels in Egypt, A Thousand Miles Up the Nile (1877), was an immediate success. During the last two decades of her life, she became concerned by threats to Egyptian monuments and antiquities, raised funds for archaeological excavations and increased public awareness by lecturing at home and abroad.

Born in London

Amelia Edwards was born in London. She was educated by her mother and it has been delivered that she showed talents in writing already at young age. Edwards published her first poem at age seven, and her first story at age 12. She continued to publish a variety of poetry, stories and articles in various magazines including the Chamber’s Journal, Household Words, and All the Year Round. Amelia Edwards also wrote for the Saturday Review and the Morning Post. She was appointed organist of St. Michael’s, Wood Green, Middlesex in 1850, at the age of 19. After several months of typhoid disease in 1849, she suffered from persistent throat complaints that also affected her voice. This and her engagement in 1851, which she entered into, although she had actually sought a relationship with another man, led to the first major change in her previous life in 1852: she resigned her position as organist and dissolved her engagement. In the next two years she gave music lessons during the day and translated Italian poetry in the evening.

A Life as a Novelist

As a novelist, Edwards’ first full length novel was published in 1855 and titled My Brother’s Wife. The book established her reputation as a novelist. Edwards spent considerable time and effort on her books’ settings and backgrounds, estimating that it took her about two years to complete the researching and writing of each. This painstaking work paid off when her last novel, Lord Brackenbury, emerged as a runaway success that went to 15 editions. The author wrote several ghost stories, including the often anthologised The Phantom Coach published in 1864. Amelia Edwards lived in her parents’ home until the death of her parents, who died only seven days apart in 1860.

Cover of “A Thousand Miles up the Nile” 1891, by Amelia Edwards

A Life of Travels

Her own earnings as a writer enabled her to travel from about 1853. She toured Europe – first Paris, Belgium, then the Rhine, France, Germany and Italy. During her stay in Rome in 1857 she met the sculptor Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908), the actress Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876) and her temporary partner, the writer Matilda Hays (1820-1897). She was supposed to have a lifelong friendship with Cushman. Edwards stayed in Paris for a long time and visited the Bohemian cafés where artists and writers met. On her travels she was initially accompanied by relatives, later by her friend Lucy Renshaw (1833-1913), whom she had met on one of these travels. Later Lucy Renshaw appears as a fictional character “L.” in her books.

Travelling the Dolomites

Untrodden Peaks and Unfrequented Valleys described Edwards’ and Renshaw’s journey through the then little-known Dolomites. The aim of this book was to present the history, botany and geology/geography of the Dolomites as well as the art, culture, customs and traditions of the inhabitants. For this reason Edwards also deviated from the usual procedure at that time of hiring travel companions from her own country of origin and hired exclusively locals for her group. Through her many years of literary experience and the mixture of (popular) scientific parts with narrative sections (for example, she described her first ascent of Sasso Bianco and Titian’s birthplace), her book appealed to a broad bourgeois audience and quickly became a success. However, she was still denied recognition from scientific circles.

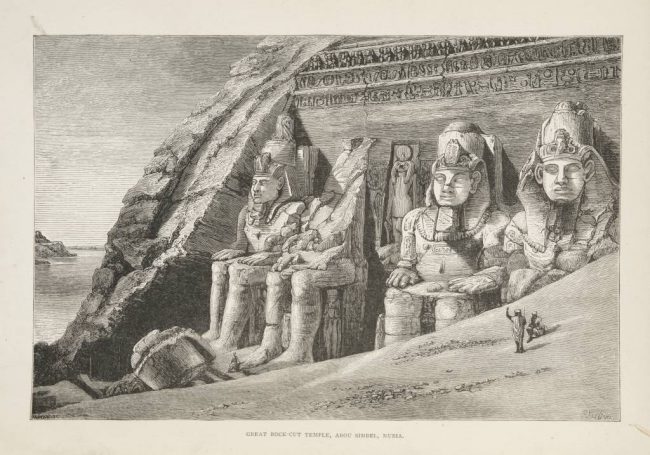

Great Temple at Abu Simbel (from A Thousand Miles up the Nile)

A Thousand Miles Up the Nile

During the winter of 1873-1874, Amelia Edwards toured Egypt with some friends. She discovered a fascination with the land and its cultures, both ancient and modern. She traveled from Cairo southwards in a hired dahabiyeh, a manned houseboat. She produced a vivid description of her Nile voyage, titled A Thousand Miles up the Nile which was published in 1877. Enhanced with her own hand-drawn illustrations, the travelogue became an immediate best-seller. Amelia Edwards was aware of the increasing threats directed towards the ancient monuments by tourism and modern development. She wanted to raise public awareness and scientific endavour, becoming a public advocate for the research and preservation of the ancient monuments. The field of Egyptology was still in its infancy in England and was mainly run by amateurs. She consulted with experts, trained herself in Egyptology, learned to read hieroglyphics and made contacts with young Egyptologists such as Gaston Maspero and Flinders Petrie.[3,4]

The Egypt Exploration Fund

Edwards co-founded the Egypt Exploration Fund – now the Egypt Exploration Society – with Reginald Stuart Poole, the curator of the Department of Coins and Medals at the British Museum. She served as joint Honorary Secretary of the Fund and served until her death. In order to be able to devote most of her time to Egyptology, Edwards mostly abandoned her literary work. She managed to contribute to the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, to the American supplement of that work, and to the Standard Dictionary. During 1889 and 1890, Amelia Edwards embarked on an ambitious lecture tour of the United States. Her lectures were later published as Pharaohs, Fellahs, and Explorers.

Legacy

Amelia Edwards died in Weston-super-Mare on 15 April 1892, shortly after being awarded an annual pension of £75 under the Civil List Act of 1837 for her services to science. From her estate a chair of Egyptology was donated to the University of London, whose first holder became Flinders Petrie according to Edwards’ last will.

Stephen Quirke, Amelia Edwards: Egyptology’s Greatest Woman (at London’s Petrie Museum), [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Amelia Edwards Biography

- [2] Amelia Edwards at the Internet Archive

- [3] Flinders Petrie and his Excavations in Egypt and Palestine, SciHi Blog

- [4] Gaston Maspero and the Sea Peoples, SciHi Blog

- [5] Amelia Edwards at Wikidata

- [6] Works by or about Amelia Edwards at Internet Archive

- [7] Works by Amelia Edwards at LibriVox

- [8] “Edwards, Amelia Ann Blanford”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8529

- [9] Stephen Quirke, Amelia Edwards: Egyptology’s Greatest Woman (at London’s Petrie Museum), heritagekeymedia @ youtube

- [10] Jenkins, Ruth Y. (2007). “More Usefully Employed: Amelia B. Edwards, Writer, Traveler and Campaigner for Ancient Egypt”. Victorian Studies. 49: 365–367.

- [11] Edwards, Amelia B. (1877). A Thousand Miles up the Nile (Second ed.). London: Longmans.

- [12] Timeline of Women Archaeologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata