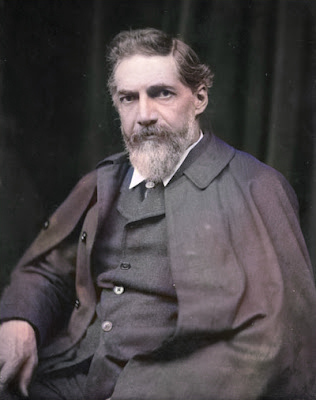

Flinders Petrie (1853-1942)

On June 3, 1853, English egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie was born. Petrie was a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egyptology in the United Kingdom, and excavated many of the most important archaeological sites in Egypt in conjunction with his wife, Hilda Petrie. Moreover, Petrie also developed the system of dating layers based on pottery and ceramic findings.

“The man who knows and dwells in history adds a new dimension to his existence…He lives in all time; the ages are his, all live alike to him”

– Flinders Petrie, Methods & Aims in Archaeology, (1904)

Flinders Petrie – Early Years

William Matthew Flinders Petrie received no formal education. However, his father taught his son how to survey accurately, laying the foundation for his archaeological career. Flinders Petrie ventured his first archaeological opinion aged eight, when friends visiting the Petrie family were describing the unearthing of the Brading Roman Villa in the Isle of Wight. The boy was horrified to hear the rough shoveling out of the contents, and protested that the earth should be pared away, inch by inch, to see all that was in it and how it lay.

Petrie already surveyed British prehistoric monuments during his teenage years. His father had corresponded with Piazzi Smyth about his theories of the Great Pyramid and Petrie travelled to Egypt in early 1880 to make an accurate survey of Giza, making him the first to properly investigate how they were constructed. Petrie’s father subscribed to Charles Piazzi Smyth’s theory that inches and feet were originally Egyptian units of measurement. With his very precise measurement, however, Petrie could only disprove the theory.

Meeting Amelia Edwards

In Petrie’s time, there was no money from the government for excavations. However, an archaeologist needed considerable financial resources: for travel, accommodation and meals, payment of workers, photographers and draftsmen, for packaging and transport, and finally for the publication of the results. So Petrie had to look for a financial backer. Returning to England at the end of 1880, Petrie wrote a number of articles and then met Amelia Edwards, journalist and patron of the Egypt Exploration Fund, who became his strong supporter and later appointed him as Professor at her Egyptology chair at University College London. Impressed by his scientific approach, they offered him work as the successor to Édouard Naville. In 1884, he started his excavations in Egypt.

Excavations in Egypt

Two years later, while working for the Egypt Exploration Fund, Petrie excavated at Tell Nebesheh in the Eastern Nile Delta. This site is located 8 miles southeast of Tanis, an area associated with the Biblical city of Zoan, and, among the remains of an ancient temple there, Petrie found a royal sphinx, now located at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Auguste Mariette [3] had uncovered the great temple of Amun there between 1859-1864. Mariette’s excavations gave rise to the later refuted assumption that Tanis was the hometown of Ramses II (Pi-Ramesse).[5]

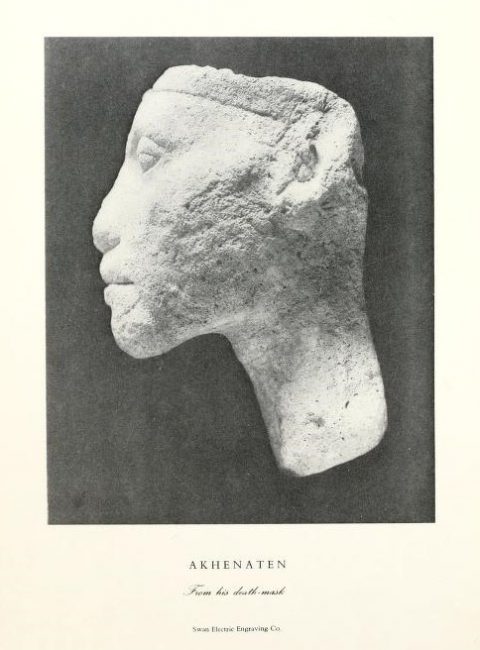

Petrie had difficulty obtaining an excavation license for Amarna from Eugène Grébaut, the head of the Antiquities Service from 1886 to 1892. He received them on condition that the rock tombs were excluded. Petrie accepted the obligation. In December 1891, Alessandro Barsanti, an employee of the Antiquities Service, began to clear the tomb of King Akhenaton, whose mummy was later discovered in tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings. The king’s tomb (Amarna tomb 26) is said to have been known to the locals since 1880. Petrie later accused Grébaut of hiding the find.

Ancient excavation sites in Egypt

Aswan and Fayum

The following year, Flinders Petrie spent cruising the Nile taking photographs as a less subjective record than sketches. During this time, he also climbed rope ladders at Sehel Island near Aswan to draw and photograph thousands of early Egyptian inscriptions on a cliff face, recording embassies to Nubia, famines and wars. At the Fayum burial site, the archaeologist found intact tombs and 60 of the famous portraits, and discovered from inscriptions on the mummies that they were kept with their living families for generations before burial.

Totenmaske Echnatons aus Amarna, W. M. Flinders Petrie: “Tell el-Amarna”, Methuen & co. London, 1894.

Palestine

During the 1890s, Petrie made the first of his many forays into Palestine, leading to much important archaeological work. He surveyed a group of tombs in the Wadi al-Rababah of Jerusalem, largely dating to the Iron Age and early Roman periods. Here, in these ancient monuments, Petrie discovered two different metrical systems.

1930 in Palestine: Flinders and Hilda Petrie (center), left Olga Tufnell (in white dress), second from right James L. Starkey, from Starkey’s obituary 1938, Palestine Exploration Fund.

The First English Chair of Egyptology

Amelia Edwards died in April 1892 and bequeathed both her large library and her Egyptian antiques to University College. This was accompanied by her legacy of £2,500 to set up the first Chair of Egyptology in England, with the proviso that the holder should not be older than 40 years and should not be connected with the British Museum. Petrie was 39 years old at the time and was indeed – as Edwards had wished – appointed to this post.

Later Years

In 1913, Petrie sold his large collection of antiques to University College, which thus owned the largest Egyptian collection in the world. During the Second World War the collection was housed partly in the basement and partly in other houses outside London, so that it suffered little damage. After World War I, Petrie had been engaged in cataloguing the museum holdings at University College before he travelled again to Egypt in 1919. In 1921 Petrie worked again on the graves in Abydos and later in Oxyrhynchos (today: Al Bahnasa, near Sandafa), where he found the remains of colonnades, remains of the theatre and parts of the necropolis. He was now 70 and the long years of his strenuous and renunciating life began to show in his health so that he travelled less to Egypt.

In 1926 Petrie decided to go to Palestine because of the unclear conditions for archaeologists in Egypt – Egypt over the border as he called it. In 1933, his doctor advised Petrie to settle in a warmer climate. He retired from his chair at University College and moved to Jerusalem, where he died in 1942.

An Excentric and…

Flinders ran a strict regiment during his excavations. He blew his whistle at sunrise to start work. He did not tolerate laziness. If he found a man sitting around, he was dismissed immediately. Petrie was a devotee of field walking. In photographs he is often seen with a long stick with which to poke the ground. This was a preparatory measure to select a single site for later excavation.

…a Pioneer

Petrie never fully learned the Egyptian language, but is nevertheless considered a pioneer in both Egyptology, archaeology, and paleopathology. In the spring of 1890, he excavated at Tell el-Hesi. During this time he explained for the first time his concept that a “tell” was a man-made mountain of successive “cities.” He introduced the dating of these “cities” by collecting and grouping their sherds, checking to what extent there was a connection with similar finds in Egypt (cross-referencing). Thus he had laid the foundation for all future work in the archaeology of the Levant.

Neal Spencer, The Pharaonic State, Nubia and the Nile River, [14]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Images and a few Infos about Flinders Petrie

- [2] Filders Petrie at the University of Manchester

- [3] Auguste Mariette and the Serapeum, SciHi Blog

- [4] Howard Carter and the Tomb of Tutankhamun, SciHi Blog

- [5] Ramesses II – King of Kings am I, SciHi Blog

- [6] More articles on egyptology at SciHi Blog

- [7] Flinders Petrie at Wikidata

- [8] Works by or about Flinders Petrie at Internet Archive

- [9] Flinders Petrie: Kahun, Gurob, and Hawara. Paul, Trench, Trübner, London 1890

- [10] Flinders Petrie, Tanis, Pt. I, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1889.

- [11] Flinders Petrie, Some Sources of Human History, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1919.

- [12] Smith, Sidney (1945). “William Matthew Flinders Petrie. 1853–1942”. Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 5 (14): 3–16.

- [13] T. E. James, “Petrie, William”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- [14] Neal Spencer, The Pharaonic State, Nubia and the Nile River, An inhabitant’s perspective from Armara West, YaleUniversity @ youtube

- [15] Timeline of English Egyptologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #42 | Whewell's Ghost