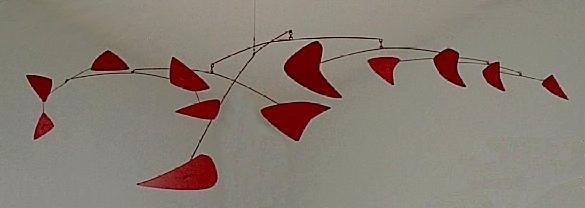

Red Mobile, 1956, Painted sheet metal and metal rods, a signature work by Alexander Calder – Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

On November 11, 1976, American sculptor Alexander Calder passed away. Calder is known as the originator of the mobile, a type of moving sculpture made with delicately balanced or suspended shapes that move in response to touch or air currents. Calder’s monumental stationary sculptures are called stabiles. He also produced wire figures, which are like drawings made in space, and notably a miniature circus work that was performed by the artist.

The Calders – A family of Sculptors

Alexander Calder was the grandson of the sculptor Alexander Milne Calder who is best known for the colossal statue of William Penn on top of Philadelphia City Hall’s tower. His father, Alexander Stirling Calder, was also a well-known sculptor who created many public installations, a majority of them in nearby Philadelphia. Calder’s mother was a professional portrait artist. At their home in Pasadena, Calder received his first set of tools. He used scraps of copper wire that he found in the street to make jewelry for his sister’s dolls.

Alexander Calder (1898 – 1976)

Hydraulic Engineering and Draughtsmanship

Despite the artistic abilities of Alexander Calder during his early life, his parents did not want him to suffer the life of an artist, so he decided to study mechanical engineering. He enrolled at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1915 and received his degree four years later. He took jobs as a hydraulic engineer and a draughtsman for the New York Edison Company after his studies and also found work as a mechanic on the passenger ship H. F. Alexander.

Finally an Artist

After his travels with the ship, Calder decided to pursue a career as an artist. In New York, Calder enrolled at the Art Students League, studying briefly with Thomas Hart Benton, George Luks, Kenneth Hayes Miller, and John Sloan. During 1926, he moved to Paris, enrolled in the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and established a studio at 22 rue Daguerre in the Montparnasse Quarter. The artist moved back to the United States and later also traveled through India.

Calder’s Kinetic Sculptures – the Cirque Calder

In 1926, Alexander Calder started to create mechanical toys and submitted them to the Salon des Humoristes. Calder began to create his Cirque Calder, a miniature circus fashioned from wire, cloth, string, rubber, cork, and other found objects. Designed to be transportable, the circus was presented on both sides of the Atlantic. Soon, his Cirque Calder became popular with the Parisian avant-garde. He also invented wire sculpture, or “drawing in space,” and in 1929 he had his first solo show of these sculptures in Paris at Galerie Billiet. It was the mixture of his experiments to develop purely abstract sculpture following his visit with Mondrian that led to his first truly kinetic sculptures, manipulated by means of cranks and motors, that would become his signature artworks. Calder’s kinetic sculptures are regarded as being amongst the earliest manifestations of an art that consciously departed from the traditional notion of the art work as a static object and integrated the ideas of gesture and immateriality as aesthetic factors.

Mobiles

In the early 1930s, Calder’s sculptures of discrete movable parts powered by motors were christened “mobiles” by Marcel Duchamp, a French pun meaning both “motion” and “motive.” He switched to hanging sculptures which derived their motion from touch or the air currents in the room and were followed in 1934 by outdoor pieces which were set in motion by the open air. At Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (1937) the Spanish pavilion included Alexander Calder’s sculpture Mercury Fountain.

Trois disques, a sculpture by Alexander Calder for Expo 67, on Saint Helen’s Island Parc Jean-Drapeau, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Postwar Art

After World War II, Calder began to cut shapes from sheet metal into evocative forms and would hand-paint them in his characteristically pure hues of black, red, blue, and white. He created a small group of works from around this period with a hanging base-plate, for example Lily of Force (1945), Baby Flat Top (1946), and Red is Dominant (1947). His 1946 show at the Galerie Louis Carré in Paris, composed mainly of hanging and standing mobiles, made a huge impact, as did the essay for the catalogue written, at the artist’s invitation, by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.[9]

Last Years

In 1963, Calder settled into a new workshop, overlooking the valley of the Lower Chevrière to Saché in Indre-et-Loire (France). He donated to the town a sculpture, which since 1974 has been situated in the town square. Throughout his artistic career, Calder named many of his works in French, regardless of where they were destined for eventual display. In 1966, Calder published his Autobiography with Pictures with the help of his son-in-law, Jean Davidson. Calder died unexpectedly in November 1976 of a heart attack, shortly after the opening of a major retrospective show at the Whitney Museum in New York. Since 1987, Calder’s artistic estate has been cared for by the New York-based Calder Foundation, which owns a large private collection. The non-profit family foundation sees its main task in cataloging the complete works and organizing posthumous exhibitions of the artist.

Alexander Calder | Lecture by author and art critic Jed Perl, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Alexander Calder Foundation Website

- [2] Alexander Calder at Britannica

- [3] Alexander Calder at Guggenheim

- [4] Alexander Calder at Wikidata

- [5] Petroski, Henry (September–October 2012). Schoonmaker, David (ed.). “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Engineer”. American Scientist. New Haven CT: Sigma XI Scientific Research Society. 100 (5): 368–373.

- [6] Russell, John (November 12, 1976). “Alexander Calder, Leading US Artist, Dies”. The New York Times.

- [7] Jed Perl: Calder : the conquest of time : the early years, 1898–1940, New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2017

- [8] Alexander Calder | Lecture by author and art critic Jed Perl, Princeton University Art Museum @ youtube

- [9] A Writer should not Allow Himself to be Turned into an Institution – Jean-Paul Sartre, SciHi Blog

- [10] ImageGrid with works of Alexander Calder, via Wikidata