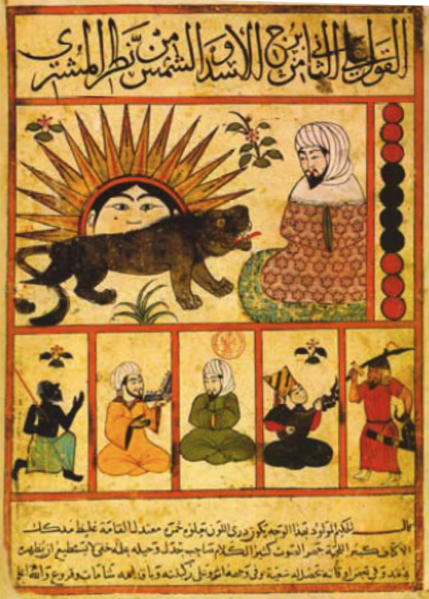

Abu Maʿshar – page of a 15th-century manuscript of the “Book of nativities”

Dear reader, we’ve realized that our daily blog on History of Science somehow is focussed on the Western view of history and the World. Of course it’s because we ourselves are part of this Western world of science. Nevertheless, we have also to include scientists and other people important for the history of science, who are not part of this Western canon of science. Today, we begin with the famous Persian astrologer, astronomer, and philosopher Abu Ma’shar al-Balkhi.

Probably on August 10, 787, Persian astrologer Abu Ma’shar, Latinized as Albumasar, was probably born. Abu Maʿshar thought to be the greatest astrologer of the Abbasid court in Baghdad. While he was not a major innovator, his practical manuals for training astrologers profoundly influenced Muslim intellectual history and, through translations, that of western Europe and Byzantium. He is known primarily for his theory that the world, created when the seven planets were in conjunction in the first degree of Aries, will come to an end at a like conjunction in the last degree of Pisces.

Born as a Member of the Intellectual Elite

Albumasar was born in the city of Balch in the province of Chorasan, then Persia. He probably came to Baghdad in the early years of al-Maʾmūn, the seventh Abbasid caliph. He probably lived on the West Side of Baghdad, near Bab Khurasan, the northeast gate of the original city on the west Bank of the Tigris. Abu Ma’shar was a member of the third generation of the Pahlavi-oriented Khurasani intellectual elite. He advocated a “most astonishing and inconsistent” eclecticism. Due to his great reputation he was probably safe from religious persecution.

Passing Down the Work of Greek Philosophers

Abu Ma’shar was a scholar of hadith, and it is believed that he only turned to astrology at the age of forty-seven, but this late start did not deter him because he was said to have lived to the ripe old age of 100 [2]. He faced a conflict with al-Kindi, back then the foremost Arab philosopher who was versed in Aristotelism and Neoplatonism. In that period, Abu Maʿshar probably realized that he had to study mathematics in order to understand philosophical arguments. Unfortunately, all works on astronomy attributed to Abu Ma’shar are lost, and only his astrological works in Arabic are known to us. His writings were held up as models of astrological practice. For instance, they provided the Italian 13th century astronomer and astrologer Guido Bonatti with a frequently cited source in his summa of Medieval Astrology, the Liber Astronomia (c. 1282). According to other sources, also the father of English literature Geoffrey Chaucer was familiar with Abu Ma’shar’s writings.[7] It was delivered that Abu Ma’shar authored a book on the variations of astronomical tables, which describes how the Persian kings gathered the best writing materials in the world to preserve their books on the sciences and deposited them in the Sarwayh fortress in the city of Jayy in Isfahan. His “Introduction” (Kitāb al‐mudkhal al‐kabīr, written c. 848) was first translated into Latin by John of Seville in 1133, as Introductorium in Astronomiam. It is one of the Arabic texts which have passed down the philosophical works of Aristotle in Arabic translation. Also, it was Abu Ma’shar who arranged for the translation into Arabic of Ptolemy‘s great treatise on astronomy, thereafter known by its Arabic title as the Almagest.

Representation of Albumasars on the astronomical clock of Nikolaus Lilienfeld

Horoscopes and Tycho Brahe

According to Abu Ma’shar, each star has particular power over a certain quality, humor, color, taste, etc., and certain genera, species, etc. in the hylic world. Together they effect all the physical and some of the psychological changes perceptible to and experienced by man, as they rotate in eternal patterns about the center and alter their positions relative to each other and to the local horizon. Those changes, it was thought, could be scientifically predicted by means of astrology. Man, however, whose soul has descended from the sphere of light, possesses free will and the potentiality of using the astrological relationships of the hylic world to the ethereal in order to alter his environment and eventually reascend to the empyrean.[5] Abu Ma’shar created horoscopes of both Muhammad and Christ. According to his interpretation of the stars, the world was created when the seven then known planets (i.e. Sun and Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) were in conjunction in the first degree of Aries. For the end of the world he also made a prediction for a similar conjunction. He was quoted by Tycho Brahe as a former critic of the peripatetics concerning the comets beyond the moon sphere, even though Abu Ma’shar’s traditional reason for the color change was not convincing.[3]

A Prolific Author

Abu Ma’shar was a very productive author and is said to have written over 50 books. In medieval Europe he was considered the most important Iranian astrologer, with great influence on the genesis of the medieval astrological world view. His books, which were translated into Latin in the 12th century, were widely used as manuscripts, but were only printed about two hundred years later. Abu Ma’shar’s introduction to astrology also received many translations to Latin and Greek starting from the 11th-century. It had significant influence on Western philosophers, like Albert the Great.[7] Another type of writings is Abu Ma’shar works on genethlialogy, the science of casting nativities. The large number of extant manuscripts suggests its high popularity in the Islamic world.

All Astronomical Works are Lost

Unfortunately, all astronomical works attributed to Abu Ma’shar are lost. However, a lot of information can still be gleaned from summaries found in the works of later astronomers or from his astrology works. Abu Maʿshar is said to have died at the age of 98 (but a centenarian according to the Islamic year count) in Wāsiṭ in eastern Iraq, during the last two nights of Ramadan of AH 272 (9 March 866).

Astronomy Across the Medieval World – HAPP Centre – Professor Christopher Cullen, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Abu Ma’shar short Biography

- [2] Abu Ma’shar al-Balkhi, From: Thomas Hockey et al. (eds.).The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, Springer Reference. New York: Springer, 2007, p. 11

- [3] Tycho Brahe – The Man with the Golden Nose, SciHi Blog

- [4] Abu Ma’shar at Wikidata

- [5] David Pingree: Abū Maʿšar, in: Encyclopædia Iranica, I/4, 337–340

- [6] Albertus Magnus and the Merit of Personal Observation, SciHi Blog

- [7] Geoffrey Chaucer – the Father of English Literature, SciHi Blog

- [8] Pingree, David (1970). “Abū Ma’shar al-Balkhī, Ja’far ibn Muḥammad”. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 32–39.

- [9] Astronomy Across the Medieval World – HAPP Centre – Professor Christopher Cullen, St Cross College @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of Astronomers of Medieval Islam, via Wikidata and DBpedia