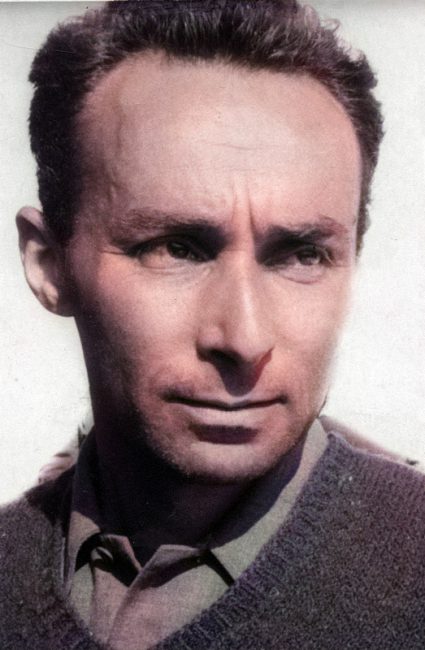

Primo Michele Levi (1919-1987)

On July 31, 1919, Italian Jewish chemist, writer, and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi was born. As a writer, he is noted for his restrained and moving autobiographical account of and reflections on survival in the Nazi concentration camps. His book The Periodic Table, a collection of short stories published in 1975, and named after the periodic table in chemistry, was named it the best science book ever by the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

“Those who deny Auschwitz would be ready to remake it.”

– Primo Levi, Interview with Daniel Toaff, Sorgenti di Vita (25 March 1983)

Primo Levi – Early Life and School

Levi was born in Turin, Italy, into a liberal Jewish family. His father Cesare, who was an avid reader, worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary. In 1925 Primo entered the Felice Rignon primary school in Turin. His school record includes long periods of absence during which time he was tutored at home. In 1930 Levi entered the Massimo d’Azeglio Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In 1933, as was expected of all young Italian schoolboys, he joined the Avanguardisti movement for young Fascists. He avoided rifle drill by joining the ski division, and spent every Saturday during the season on the slopes above Turin. In 1934, he sat the exams for the Massimo d’Azeglio liceo classico and was admitted that autumn. Upon reading Concerning the Nature of Things by Sir William Bragg, Levi decided that he wanted to be a chemist.[4]

Levi matriculated from the school in 1937 despite being accused of ignoring a call-up to the Italian Royal Navy the week before his exams were due to begin. Due to a nervous breakdown he failed in his Italian exams. He further avoided the compulsory two-year spell in the Navy by voluntarily enlisting in the ranks of the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, a paramilitary fascist group. He finally passed his Italian exam, and enrolled at the University of Turin, to study chemistry. By 1938, Italy passed anti-Jewish legislation and Italian Jews lost their basic civil rights, their positions in public offices, and their assets. Jewish students who had begun their course of study were permitted to continue, but new Jewish students were barred from entering university. Levi‘s having matriculated a year early enabled him to take a degree.

“For me chemistry represented an indefinite cloud of future potentialities which enveloped my life to come in black volutes torn by fiery flashes, like those which had hidden Mount Sinai. Like Moses, from that cloud I expected my law, the principle of order in me, around me, and in the world. ”

(Primo Levi, The Periodic Table, 1975)

Chemistry and Surviving Auschwitz

Because of the new Race Laws and the increasing intensity of prevalent Fascism, Levi had difficulty finding a supervisor for his graduation thesis. Eventually taken on by Dr. Nicolò Dallaporta, he graduated in the summer of 1941, but the racial laws prevented Levi from finding a suitable permanent job after he had graduated. Primo worked under a false name at an asbestos mine at San Vittore, when he was recruited through a fellow student on a project to extract an anti-diabetic from vegetable matter for a Swiss company, because the racial laws did not apply to Swiss companies. It soon became clear that the project had no chance of succeeding, but it was in no one’s interest to say so. The Italian resistance movement became increasingly active in the German-occupied zone. Levi and a number of comrades took to the foothills of the Alps, and in October formed a partisan group in the hope of being affiliated to the liberal Giustizia e Libertà resistance movement. Completely untrained for such a venture, he and his companions were arrested by the Fascist militia on 13 December 1943. However, when he and his comrades were arrested by Fascist forces, Levi admitted he was a Jew to avoid being shot as a partisan and was sent to an Italian prison camp at Fossoli near Modena, before being deported on 21 February 1944 to the German death camp Auschwitz.[2] He spent eleven months there before the camp was liberated by the Red Army on 18 January 1945. Of the 650 Italian Jews in his transport, Levi was one of twenty who left the camps alive. The average life expectancy of a new entrant at the camp was three months. He was only able to survive, because of his skills as being a trained chemist. Rubber had become rare in war times and the IG Farben‘s Buna Werke laboratory near Auschwitz was intended to produce synthetic rubber. But, they were short of chemists and recruited chemists among the concentration camp prisoners. Although liberated on 27 January 1945, Levi did not reach Turin until 19 October 1945.

“We who survived the Camps are not true witnesses. We are those who, through prevarication, skill or luck, never touched bottom. Those who have, and who have seen the face of the Gorgon, did not return, or returned wordless.”

– Primo Levi, as quoted in The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991 (1994)

Levi’s Career as a Writer

Looking for work in Milan, he began to tell people he met on the train stories about his time at Auschwitz. At about 1946, he started writing poetry about his experiences in Auschwitz. Levi started work at a Du Pont Company paint factory outside Turin. Because of the extremely limited train service, Levi stayed in the factory dormitory during the week. This gave him the opportunity to write undisturbed and he started to write the first draft of If This Is a Man (later published as Survival in Auschwitz). On 22 December 1946, the manuscript was complete. There, Levi demonstrated extraordinary qualities of humanity and detachment in its analysis of the atrocities he had witnessed. In 1947, Levi teamed up with an old friend Alberto Salmoni to run a chemical consultancy. Their attempts to make lipsticks from reptile excreta and a coloured enamel to coat teeth were turned into short stories. In the decade that followed, Levi turned his attention to family life, marrying Lucia Morpurgo, with whom he would have two children, before returning to a position at a paint factory. [2] In 1958, a new edition of If This Is a Man was published, and in 1959 it was translated into both English and German. This renewed interest in his work brought Levi a certain measure of his success.

Once more he sees his companions’ faces

Livid in the first faint light,

Gray with cement dust,

Nebulous in the mist,

Tinged with death in their uneasy sleep.

At night, under the heavy burden

Of their dreams, their jaws move,

Chewing a non-existant turnip.

‘Stand back, leave me alone, submerged people,

Go away. I haven’t dispossessed anyone,

Haven’t usurped anyone’s bread.

No one died in my place. No one.

Go back into your mist.

It’s not my fault if I live and breathe,

Eat, drink, sleep and put on clothes.’

(Primo Levi, The Survivor)

The Periodic Table

Levi began writing The Truce early in 1961 and it won the first annual Premio Campiello literary award. It is often published in one volume with If This Is a Man, as it covers his long return through eastern Europe from Auschwitz. He wrote two other highly praised memoirs, Moments of Reprieve (1978) and The Periodic Table (1975). Moments of Reprieve deals with characters he observed during imprisonment. The Periodic Table, a book on the analogies between the physical, chemical, and moral spheres, is arguably his most important and famous work. It is a collection of 21 autobiographical stories that each use a chemical element as a starting point, covering everything from Levi’s childhood and schooling to life in and after Auschwitz.[2] At London‘s Royal Institution on 19 October 2006, The Periodic Table was voted onto the shortlist for the best science book ever written.

Levi had allegedly died falling from the interior landing of his third-story apartment in Turin to the ground floor below on 11 April 1987. According to witnesses it was a case of suicide.[1]

.

Elie Wiesel Memorial Lecture by Sharon Portnoff on “Primo Levi: Testimony of an Auschwitz Survivor”, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Primo Levi at The Famous People

- [2] Primo Levi at Biographies.com

- [3] Primo Levi at Britannica Online

- [4] Sir William Henry Bragg and his Work with X-Rays, SciHi Blog

- [5] Primo Levi at Wikidata

- [6] BBC Interview with Primo Levi

- [7] Works by or about Primo Levi at Internet Archive

- [8] “Primo Levi’s journeys of peace”: an article in the TLS by Clive Sinclair, 11 July 2007

- [9] Gabriel Motola (Spring 1995). “Primo Levi, The Art of Fiction No. 140”. The Paris Review. Spring 1995 (134).

- [10] Elie Wiesel Memorial Lecture by Sharon Portnoff on “Primo Levi: Testimony of an Auschwitz Survivor”, 2019, Boston University @ youtube

- [11] Levi, Primo (17 February 1986). “Primo Levi’s Heartbreaking, Heroic Answers to the Most Common Questions He Was Asked About “Survival in Auschwitz”“. The New Republic.

- [12] Anissimov, Myriam (1999). Primo Levi: Tragedy of an Optimist. New York: Overlook.

- [13] Timeline for Primo Levi, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #51 | Whewell's Ghost