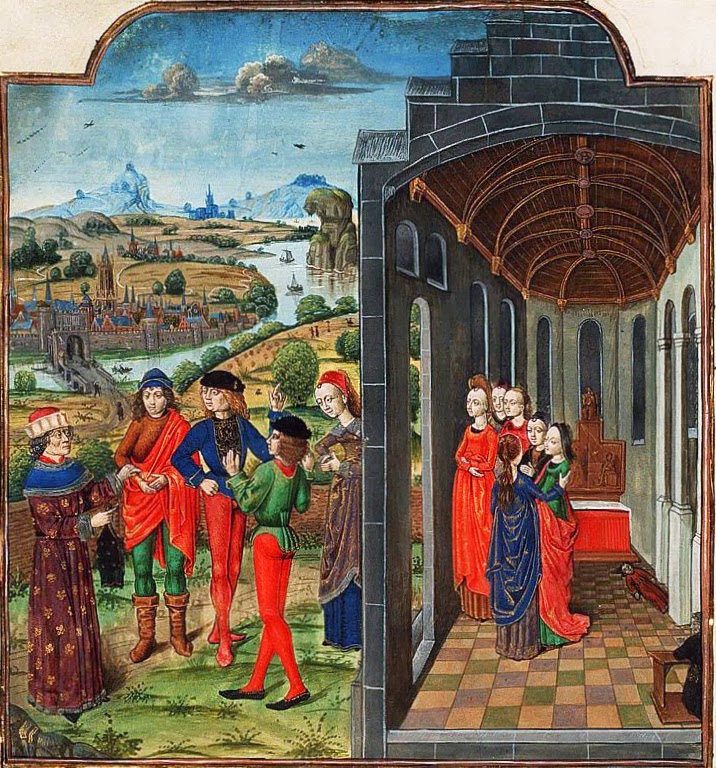

Giovanni Boccaccio and Florentines who have fled from the plague

On December 21, 1375, Italian author, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and important Renaissance humanist Giovanni Boccaccio passed away. He is best known for his masterpiece ‘The Decameron‘ told as a frame story encompassing 100 tales.

You haven’t heart about the ‘Decameron‘? You definitely should, simply because it is the masterpiece of European Renaissance literature. In its 100 stories it provides us with an intimate contemporary view into medieval and early Renaissance European society. But, before I will tell you more about its content, let me introduce its genius creator to you, the author, poet, and important humanist Giovanni Boccaccio.

“While farmers generally allow one rooster for ten hens, ten men are scarcely sufficient to service one woman.”

(Giovanni Boccaccio, from ‘The Decameron’)

Giovanni Boccaccio – Family Background

The details of Giovanni Boccacio’s birth are rather uncertain. He was born in Florence or in a village near Certaldo where his family was from. He was likely born out of wedlock to his father Boccaccino di Chellino, a Florentine merchant, and grew up in Florence. Boccaccio may have received an early introduction to the works of Dante by his tutor Giovanni Mazzuoli. In 1326, Boccaccio’s family moved to Naples, where his father was appointed head of a bank. As usual in these days, Boccaccio was supposed to follow his father into the banking profession. Although already an apprentice at the bank, Boccaccio succeeded to persuade his father to let him study canon law for the next six years, where he also pursued his interest in scientific and literary studies.

“Heaven would indeed be heaven if lovers were there permitted as much enjoyment as they had experienced on earth”.

(Giovanni Boccaccio)

Boccaccio meets Petrarch

It seems Boccaccio enjoyed law no more than banking, but his studies allowed him the opportunity to study widely and make good contacts with fellow scholars. At Naples he began to write first stories in verse and prose, mingled in courtly society, and fell in love with a noble lady whom he made famous under the name of Fiammetta in his writings. After the death of his father in 1348, Boccaccio returned to Florence and became guardian to his younger brother while maintaining public offices in Florence. Meanwhile, he was trying continually to put his financial affairs in order, though he never succeeded in doing so. It was in 1350, when Boccaccio’s lifelong friendship with Petrarch began. Boccaccio made a deep friendship with him. Both shared a veneration for classical authors, as their correspondence testifies, in which they exchanged literary experiences. Both writers often worked closely with each other and together their works are considered by some to be the foundation of humanist literature.[5] Soon a circle of intellectuals developed around Petrarch and Boccaccio, who rediscovered some important classical works, including the Annals of Tacitus and the Metamorphoses of Apuleius.

“A kissed mouth doesn’t lose its freshness, for like the moon it always renews itself.”

(Giovanni Boccaccio, from ‘The Decameron’)

Circes: illustration of one of the women featured the 1374 biographies of 106 famous women, De Claris Mulieribus, by Boccaccio – from a German translation of 1541

The Decameron – Boccaccios’s Masterpiece

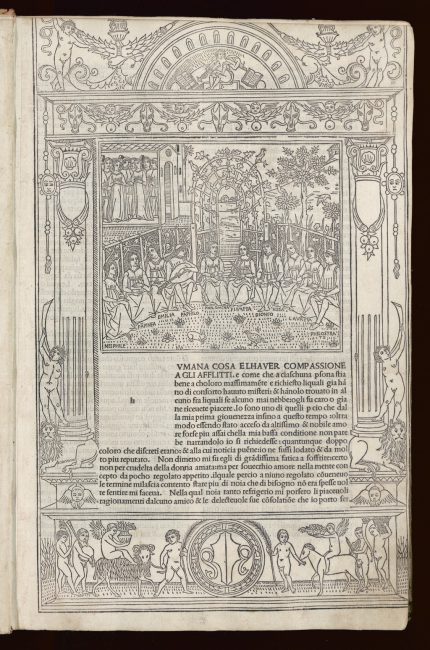

Boccaccio completed the great Decameron in 1358 in the form in which it is read today. It narrates hundred stories of seven women and three men who reside in a country villa for ten days after escaping from the plague in Florence. In the broad sweep of its range and its alternately tragic and comic views of life, it is rightly regarded as his masterpiece. The tales treat a wide variety of characters and events and brilliantly reveal humanity as sensual, tender, cruel, weak, self-seeking, and ludicrous. Boccaccio presents life from an earthly point of view, with a complete absence of moral intentions. If nothing is sacred, if a corrupt clergy is shown in all its greed and vanity, this offers stuff for amusement but never satire. Stylistically, the Decameron is the most perfect example of Italian classical prose, and its influence on Renaissance literature throughout Europe was enormous, as e.g. great writers such as Shakespeare [7] and Chaucer [6] are known to have borrowed a lot. Also renowned poets such as George Eliot, Tennyson, Keats, Longfellow and Swinburne have written poems revolving around the Decameron. Boccaccio on the other hand was impressed by the works of Dante and conducted lectures on his poems in 1373.

“Do as we say, and not as we do.”

(Giovanni Boccaccio, from ‘The Decameron’)

Illustration from a ca. 1492 edition of Il Decameron published in Venice

Later Life

After Boccaccio had begun to study Greek around 1360, he succeeded in establishing the first chair in Florence. This was awarded to Leontius Pilate, to whom Boccaccio also entrusted the translation of the Iliad and Homer‘s Odyssey into Latin. These works could thus be read by a much wider audience. His interest in antiquity also influenced the production of literature towards the end of his life. In his later years he wrote less narrative texts in Volgare, but more works in Latin on encyclopaedic or philological themes. This change may also be due to a religious crisis in Boccaccio’s life. This is said to have been so profound that Boccaccio even wanted to destroy some of his works, which he now considered immoral. However, he was able to be held back by Petrarch. This account is called into question by the fact that he was still making copies of his Decamerone in his own hand around 1370. He had already entered the inferior clergy in 1360, although probably due to financial hardship. Finally, in 1362, he met the Carthusian monk Gioachino Cianni from Siena, who converted Boccaccio to “pious life”. In 1373, the city of Florence instructed him, who had already fomented the cult of Dante Alighieri twenty years earlier with his Dante biography, to publicly read, explain and comment on the Divina Commedia. In 1374, however, his health deteriorated due to a probable hydropsy and he had to stop this activity.[8]

A Tale from the Decameron (1916) by John William Waterhouse.

Final Years

During his last years Boccaccio lived principally in retirement at Certaldo, and would have entered into holy orders, moved by repentance for the follies of his youth, had he not been dissuaded by Petrarch. Soon after the death of his older friend Petrarch, Boccacio passed away at age 62 on Dec. 21, 1375, in Certaldo, where he is also burried.

Jason Houston, Boccaccio’s Decameron: a guide to life after the Plague, [13]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Decameron Web

- [2] Giovanni Boccaccio at Famous Authors

- [3] Giovanni Boccaccio at the Encyclopedia Britannica

- [4] Full Text of The Decameron – in English and Italian

- [5] Francesco Petrarca and the Invention of the Renaissance, SciHi Blog

- [6] Geoffrey Chaucer – the Father of English Literature, SciHi Blog

- [7] Brush Up Your Shakespeare, SciHi Blog

- [8] Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy, SciHi Blog

- [9] Works by or about Giovanni Boccaccio at Wikisource

- [10] Works by or about Giovanni Boccaccio at Internet Archive

- [11] Giovanni Boccaccio at Wikidata

- [12] Giovanni Boccaccio at the German Digital Library

- [13] Jason Houston, Boccaccio’s Decameron: a guide to life after the Plague, the British Institute of Florence, The Biflorence @ youtube

- [14] Bartlett, Kenneth R. (1992). “Florence in the Renaissance”. The Civilization of the Italian Renaissance: A Sourcebook. Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath.

- [15] Timeline for Giovanni Boccaccio, via Wikidata