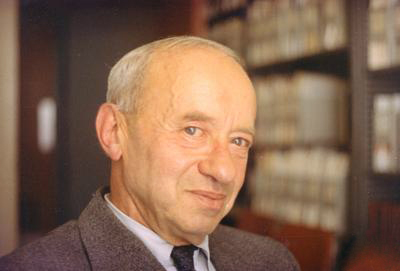

Alfred Tarski (1901-1983), photo: George Bergman – The Oberwolfach photo collection, GFDL

On January 14, 1902, Polish-American mathematician and logician Alfred Tarski was born. A prolific author he is best known for his work on model theory, metamathematics, and algebraic logic, he also contributed to abstract algebra, topology, geometry, measure theory, mathematical logic, set theory, and analytic philosophy. For my Semantic Web Technologies lecture series I always introduce my students to model-theoretic semantics as means to enable a formal representation of meaning for languages. I guess, they don’t like the mathematical overhead. But nevertheless, you need it to make sense of any logical expression.

“Logic is justly considered the basis of all other sciences, even if only for the reason that in every argument we employ concepts taken from the field of logic, and that ever correct inference proceeds in accordance with its laws.”

— Alfred Tarski, Introduction to Logic: and to the Methodology of Deductive Sciences. (1941/2013)

Alfred Tarski – Youth and Education

Born as Alfred Teitelbaum into a family of Polish Jews of comfortable circumstances, Tarski first manifested his mathematical abilities while in secondary school, at Warsaw’s Szkoła Mazowiecka. Nevertheless, he entered the University of Warsaw in 1918 intending to study biology. After Poland regained independence in 1918, Warsaw University quickly became a world-leading research institution in logic, foundational mathematics, and the philosophy of mathematics. Famous Mathematician Stanisław Leśniewski recognized Tarski’s potential as a mathematician and encouraged him to abandon biology. Henceforth Tarski attended courses taught by Jan Łukasiewicz, Wacław Sierpiński, and became the only person ever to complete a doctorate under Leśniewski’s supervision.

The youngest PhD at Warsaw University

In 1923, Alfred Teitelbaum and his brother Wacław changed their surname to Tarski and also converted to Roman Catholicism, Poland’s dominant religion, even though Tarski was an avowed atheist. After completing his doctorate at Warsaw University 1923, Tarski served as Łukasiewicz’s assistant. Tarski’s first major results were published in 1924 when he began building on the set theory results obtained by Cantor, Zermelo and Dedekind. He published a joint paper with Banach in that year on what is now called the Banach-Tarski paradox.[1] Between 1923 and his departure for the United States in 1939, Tarski not only wrote several textbooks and many papers, a number of them ground-breaking, but also did so while supporting himself primarily by teaching high-school mathematics at Warsaw secondary school, because of the small salary at Warsaw University. In 1930, Tarski visited the University of Vienna, lectured to Karl Menger’s colloquium, and met Kurt Gödel.[4] Due to an invitation from Harvard University, Tarski was able to leave Poland in August 1939, on the last ship to sail from Poland for the United States before the German and Soviet invasion of Poland and the outbreak of World War II.

Emigration to the U.S.

Tarski left reluctantly, because Leśniewski had died a few months before, creating a vacancy which Tarski hoped to fill. Oblivious to the Nazi threat, he left his wife and children in Warsaw. He did not see them again until 1946. During the war, nearly all his extended family died at the hands of the German occupying authorities. Thanks to a Guggenheim Fellowship, Tarski visited the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in 1942, where he again met Gödel, who also had fled from Nazi Germany. Subsequently, he joined the Mathematics Department at the University of California, Berkeley, where he spent the rest of his career until he became emeritus in 1968.

Scientific Work

Tarski was a charismatic teacher who charmed his students, but he demanded perfection and could be devastatingly abusive to those who failed to measure up.[3] He is recognised as one of the four greatest logicians of all time, the other three being Aristotle, Frege, and Gödel. Of these Tarski was the most prolific as a logician and his collected works, excluding his books, runs to 2500 pages. Tarski made important contributions in many areas of mathematics: set theory, measure theory, topology, geometry, classical and universal algebra, algebraic logic, various branches of formal logic and metamathematics. He produced axioms for ‘logical consequence‘, worked on deductive systems, the algebra of logic and the theory of definability. He can be considered a mathematical logician with exceptionally broad mathematical interests.[1]

One example of his achievements is a decision procedure for sentences written in the language of the arithmetic of real numbers. These are sentences that can be written using variables ranging over the real numbers, using symbols for the operations of addition and multiplication and for the relations of equality and order .[3]

“It is perhaps worth while saying that semantics as conceived in this paper (and in former papers of the author) is a sober and modest discipline which has no pretensions to being a universal patent-medicine for all the ills and diseases of mankind, whether imaginary or real. You will not find in semantics any remedy for decayed teeth or illusions of grandeur or class conflicts. Nor is semantics a device for establishing that everyone except the speaker and his friends is speaking nonsense.”

— Alfred Tarski, The Semantic Conception of Truth (1952)

The Notion of Truth and the Undefinability Theorem

Another great achievement was his assault on the notion of truth. Tarski was able, under suitable conditions, to give a mathematically precise definition of what it means to say that a given sentence of a language is true. One of these conditions was that the syntax of the language in question be formally well-defined, i.e. one could say precisely just which expressions are legitimate sentences and which not. Moreover, a sentence had to have a well-defined semantics, i.e. the meaning of the individual components of the sentence had to be (formally) given. Now, the “metalanguage” in which this truth definition is developed is, in general, separate from the language whose true sentences are being identified. As Kurt Gödel previously had shown, it is possible for a language to function as its own metalanguage. But for this case, Tarski was able to prove his famous “undefinability theorem“: Under very general conditions, the notion of “truth” of the sentences of a language cannot be defined in that same language.[3] Thus, Tarski radically transformed Hilbert’s proof-theoretic metamathematics. He destroyed the borderline between metamathematics and mathematics by his objection to restricting the role of metamathematics to the foundations of mathematics

Alfred Tarski died on October 26, 1983, in Berkeley, California, at age 82.

Matthias Baaz: Kurt Gödel and Alfred Tarski:The Extremes of Logic, [9]

References and Further Reading

- [1] Alfred Tarski at McTutor’s history of Mathematics

- [2] Alfred Tarski at biography.yourdictionary.com

- [3] Martin Davis: The Man who defined Truth, book review at americanscientist.org, 2005.

- [4] Kurt Gödel Shaking the Very the Foundations of Mathematics, SciHi Blog, April 28, 2012.

- [5] Alfred Tarski at zbMATH

- [6] Alfred Tarski at Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [7] Alfred Tarski at Wikidata

- [8] Tarski’s Truth Definitions by Wilfred Hodges, Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

- [9] Matthias Baaz: Kurt Gödel and Alfred Tarski:The Extremes of Logic, 2021, Logic, Philosophy and Gödel @ youtube

- [10] Blok, W. J.; Pigozzi, Don, “Alfred Tarski’s Work on General Metamathematics”, The Journal of Symbolic Logic, Vol. 53, No. 1 (Mar., 1988), pp. 36–50

- [11] Sinaceur H (2001). “Alfred Tarski: Semantic shift, heuristic shift in metamathematics”. Synthese. 126: 49–65.

- [12] Alfred Tarski, 1944. “The Semantical Concept of Truth and the Foundations of Semantics,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 4: 341–75

- [13] Alfred Tarski, 1969. “Truth and Proof“, Scientific American 220: 63–77.

- [113] Timeline of logicians, via Wikidata