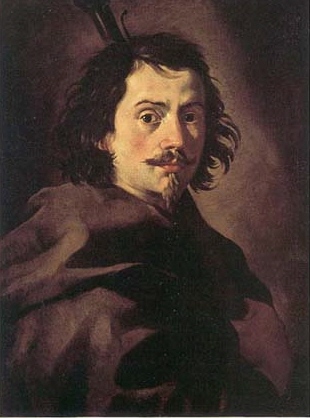

Francesco Borromini (1599 – 1667)

On Sep 25, 1599, Italian architect Francesco Borromini was born. With his contemporaries Gian Lorenzo Bernini [1] and Pietro da Cortona, Borromini was a leading figure in the emergence of Roman Baroque architecture. A keen student of the architecture of Michelangelo and the ruins of Antiquity, Borromini developed an inventive and distinctive, if somewhat idiosyncratic, architecture employing manipulations of Classical architectural forms, geometrical rationales in his plans and symbolic meanings in his buildings.

“Those who follow others never go before them. And I certainly wouldn’t have gone into this profession in order to be just a copyist.”

– Francesco Borromini, from Opus architectonicum, edited by Maurizio De Benedictis, De Rubeis, 1993

Francesco Borromini – Early Years

Borromini was born at Bissone, near Lugano in the Ticino, which was at the time a bailiwick of the Swiss Confederacy. He was the son of a stonemason and began his career as a stonemason himself. He soon went to Milan to study and practice his craft. At a young age, Francesco Castelli arrived in Milan and received training as a stonemason in the cathedral building hut there. After his apprenticeship he settled in Rome. There he adopted the suffix Borromini, possibly in honour of Saint Charles Borromeo. From 1619 Borromini worked in the building hut at St. Peter’s, which was led by his uncle Carlo Maderno. During this time he intensively studied antiquity and especially the works of his great role model Michelangelo.[2] With his mentor and teacher Maderno he worked at Palazzo Barberini until he died. Gian Lorenzo Bernini took over the construction management and was also appointed architect of Saint Peter. Borromini worked under him as an assistant. After just a few years, the two of them quarreled and broke up, and a lifelong rivalry began.

Who is the leading Roman Baroque Architect?

Pope Innocent X (1644-1655) placed his trust in Borromini, which enabled him in the following years to oust his archrival Bernini from the position of the leading Roman architect. But already under the next pope, Alexander VII. (1655-1667), Borromini lost this position and was only sparsely entrusted with new commissions. Bernini’s star, on the other hand, shone again in full splendour. Borromini dedicated himself to the extension and completion of buildings that had already begun, such as the interiors of the churches of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, Sant’Andrea delle Fratte and San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome. He also completed the basement of the façade of his first work, the small church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane on the Quirinal in Rome.

Saint’Ivo alla Sapienza

From 1640-1650, he worked on the design of the church of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza and its courtyard, near University of Rome La Sapienza palace. It was initially the church of the Roman Archiginnasio. He had been initially recommended for the commission in 1632, by his then supervisor for the work at the Palazzo Barberini, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The site, like many in cramped Rome, is challenged for external perspectives. It was built at the end of Giacomo della Porta’s long courtyard. The dome and cochlear steeple are peculiar, and reflect the idiosyncratic architectural motifs that distinguish Borromini from contemporaries. Inside, the nave has an unusual centralized plan circled by alternating concave and convex-ending cornices, leading to a dome decorated with linear arrays of stars and putti. The geometry of the structure is a symmetric six-pointed star; from the center of the floor, the cornice looks like a two equilateral triangles forming a hexagon, but three of the points are clover-like, while the other three are concavely clipped. The innermost columns are points on a circle. The fusion of feverish and dynamic baroque excesses with a rationalistic geometry is an excellent match for a church in a papal institution of higher learning.

Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza in Rome

Borromini’s New Expressiveness

While Bernini’s formal language follows the classical canon and can largely be traced back to the model of Michelangelo, Borromini endeavoured to give architecture a new expressiveness through an individual interpretation of classical architectural forms. He worked with three-dimensionally, even organically shaped, mostly entirely white interiors and concave curved facades. His idiosyncratic inventions earned him the reputation of being extravagant, “bizarre” and “Gothic”. An example of this is the “perspective” in the courtyard of the Palazzo Spada in Rome: the columns, which become smaller at the back, suggest a spatial depth extension that in reality does not even exist, and in the end make the figure appear much larger than it actually is.

Suicide

In the summer of 1667 he was overcome with depression, which finally led to his taking his own life on 2 August, 1667. In his testament, Borromini wrote that he did not want any name on his burial and expressed the desire to be buried in the tomb of his kinsman Carlo Maderno in San Giovanni dei Fiorentini. In recent times, his name was added on the marble plaque below the tomb of Maderno and a commemorative plaque commissioned by the Swiss embassy in Rome was placed on a pillar of the church.

Aftermath

In his immediate aftermath, he initially lagged behind Bernini. He only found a successor in Guarino Guarini. In the 18th century, the late Baroque era, his decorative style, which was spread by engravings, was imitated in many places, for example in the Roman church of Santa Maria Maddalena built by Giuseppe Sardi in 1735. Most of Borromini’s graphic oeuvre is now in the Albertina Collection of Prints and Drawings in Vienna. As an artist born in present-day Switzerland, Borromini was depicted on the 100 Swiss franc banknote of the 1980s. On the occasion of Borromini’s 400th birthday celebrations, a 33 m high wooden model was erected in Lugano under the direction of Mario Botta, showing the original scale cut through the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane.

Geometry and motion in Borromini’s San Carlo, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Gian Lorenzo Bernini – Master Architect and Sculptor of the Italian Baroque, SciHi Blog

- [2] Michelangelo Buonarotti – the Renaissance Artist, SciHi Blog

- [3] Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911, article on Francesco Borromini

- [4] Columbia University: Joseph Connors, Francesco Borromini: Opus Architectonicum, Milan, 1998: Introduction to Borromini’s own description of the Casa dei Filippini

- [5] Borromini’s own account of his eventually successful suicide attempt

- [6] Francesco Borromini at Wikidata

- [7] Geometry and motion in Borromini’s San Carlo, Smarthistory @ youtube

- [8] Carboneri, Nino. “Francesco Borromini”. Dizionario biografico degli Italiani. Treccani.

- [9] Map with buildings by Francesco Borromeo, via Wikidata