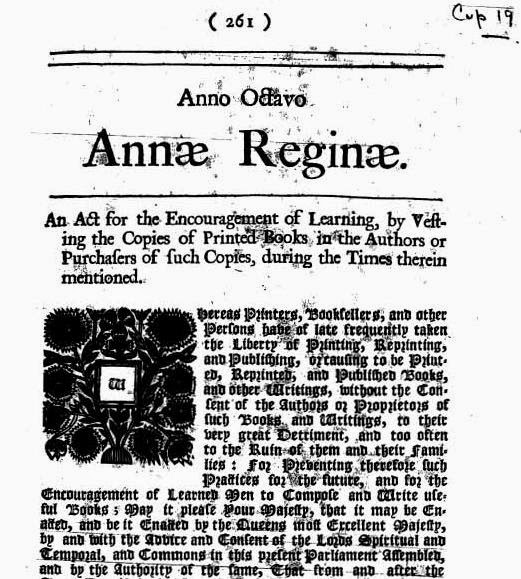

Statute of Anne, the first modern copyright law.

On April 10, 1710, the Statute of Anne, an act of the Parliament of Great Britain, was introduced. It was the first statute to provide for copyright regulated by the government and courts, rather than by private parties.

Literary Works under Richard III

With the introduction of the printing press to Britain by William Caxton in 1476, printed works became more and more important as an economic asset. As early as 1483, King Richard III recognized the value of literary works by specifically exempting them from the government’s protectionist legislation. Over the next fifty years, the government moved further towards economic regulation, abolishing the provision with the Printers and Binders Act 1534, which also banned the import of foreign works (except of works written in Latin or Greek) and empowered the Lord Chancellor to set maximum pricing for British books. This was followed by increasing degrees of censorship. A further proclamation of 1538, aiming to stop the spread of Lutheran doctrine, noted that “sondry contentious and sinyster opiniones, have by wrong teachynge and naughtye bokes increaced and growen within this his realme of England“. Henceforth, King Henry VIII declared that all authors and printers must allow the Privy Council or their agents to read and censor books before publication.

Licensing Act of 1662

Prior to the statute’s enactment in 1710, copying restrictions were authorized by the Licensing Act of 1662. These restrictions were enforced by the Stationers’ Company, a guild of printers given the exclusive power to print as well as to censor all literary works. The censorship administered under the Licensing Act finally led to public protest. As the act had to be renewed at two-year intervals, authors and others sought to prevent its re-authorization. When the Parliament refused to renew the Licensing Act in 1694, the Stationers’ monopoly and press restrictions came to an end.

Statute of Anne

The Statute of Anne also is considered a “watershed event in Anglo-American copyright history transforming what had been the publishers’ private law copyright into a public law grant“. Under the statute, copyright was for the first time vested in authors rather than publishers. It also included provisions for the public interest, such as a legal deposit scheme. Consisting of 11 sections, the Statute of Anne is formally titled “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of Copies, during the Times therein mentioned“. The Statute then moved on to stating the nature of copyright. The right granted was the right to copy; to have sole control over the printing and reprinting of books, with no provision to benefit the owner of this right after the sale.

The Act also brought about the depositing of nine copies of a book to certain libraries throughout the country. Once registration had been completed and the deposits were made, the author was granted an exclusive right to control the copying of the book. Penalties for infringing this right were severe, with all infringing copies to be destroyed and large fines to be paid to both the copyright holder and the government; there was only a three-month statute of limitations on bringing a case, however. This exclusive right’s length was dependent on when the book had been published and ranged between 14 and 21 years. An author who survived until the copyright expired would be granted an additional 14-year term, and when that ran out, the works would enter the public domain.

The Statute of Anne is traditionally seen as a historic moment in the development of copyright, and the first statute in the world to provide for copyright. It also marked the first time that copyright had been vested primarily in the author, rather than the publisher, and also the first time that the injurious treatment of authors by publishers was recognised.

Cory Doctorow, How Copyright Threatens Democracy, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Roman Legal Tradition and the Compilation of Justinian

- [2] Scans and transcription of the Statute of Anne, as published 1710

- [3] The History of Copyright at the Intellectual Property Office

- [4] The Codex Justinianus and the Origins of Jurisdiction, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Statute of Ann at Wikidata

- [6] Cory Doctorow, How Copyright Threatens Democracy, New America @ youtube

- [7] Bracha, Oren (2010). “The Adventures of the Statute of Anne in the Land of Unlimited Possibilities: The Life of a Legal Transplant”. Berkeley Technology Law Journal. UC Berkeley School of Law. 25 (1).

- [8] Deazley, Ronan (2003). “The Myth of Copyright at Common Law” (PDF). Cambridge Law Journal. Cambridge University Press. 62 (1): 106–133.

- [9] Holdsworth, William (1920). “Press Control and Copyright in the 16th and 17th Centuries”. Yale Law Journal. Yale Law School. 29 (1).