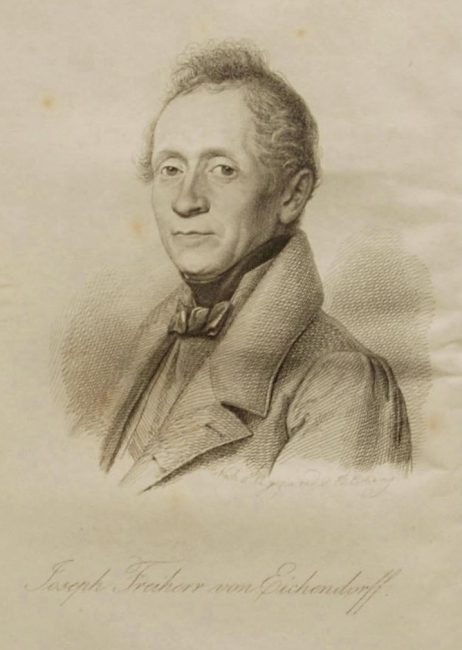

Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857)

On March 10, 1788, German writer Joseph Karl Benedikt Freiherr von Eichendorff was born. He was an important poet and writer of German Romanticism. With around 5000 settings, he is one of the most widely acclaimed German-language lyricists and is still present today as a prose poet.

“You good-for-nothing! there you sun yourself again and stretch and stretch your bones tiredly, and leave me to do all the work alone. I can no longer feed you here. Spring is at the door, go out into the world and buy yourself your own bread”.

– Joseph von Eichendorff, Memoirs of a Good-for-Nothing, (1826) First Chapter, the miller to his son

Early Years

Eichendorff’s parents were the Prussian officer Adolf Theodor Rudolf Freiherr von Eichendorff (1756-1818) and his wife Karoline née Freiin von Kloch (1766-1822). His mother came from a Silesian noble family, from whose possession she inherited Schloss Lubowitz near Ratibor, Upper Silesia, today Racibórz, Czech Republic. There, Joseph von Eichendorff was born in 1788. From 1793 to 1801 he was taught at home together with his brother Wilhelm von Eichendorff by priest Bernhard Heinke. In addition to extensive reading of adventure and knightly novels and ancient legends, the first childish literary attempts followed. In 1794 he travelled to Prague. On November 12, 1800, his diary entries and the writing of a natural history with his own illustrations began.

School and Travels

In October 1801 Joseph and Wilhelm began attending the Catholic Matthias Grammar School in Breslau. Frequent visits to the theatre and early poems are known from this period. The youth friendship with his classmate Joseph Christian von Zedlitz was also founded here. From 1805 to 1806 Eichendorff studied law in Halle and also attended philological lectures with Friedrich August Wolf, Friedrich Schleiermacher and Henrich Steffens. A journey through the Harz Mountains took him as far as Hamburg and Lübeck. In August 1806 Eichendorff returned to Schloss Lubowitz, where he enjoyed social life with balls and hunting in the surrounding area.

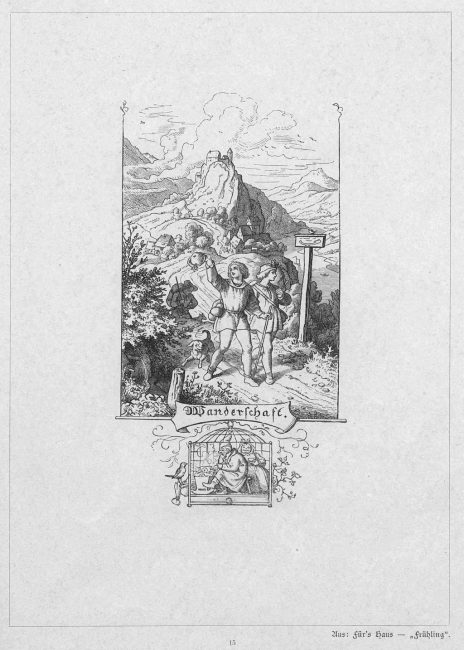

‘Wanderschaft by Ludwig Richter, illustration for Eichendorff’s poem The Happy Wanderer, woodcut 1858-61

University and First Poetry

In May 1807 the brothers drove via Linz, Regensburg and Nuremberg to Heidelberg to continue their studies. Eichendorff attended lectures in law there with famous jurist Anton Friedrich Justus Thibaut, but also attended those with Catholic publisher and natural philosopher Joseph Görres. He became known fleetingly with Achim von Arnim;[1] a closer friendship connected him with the poet Otto von Loeben. Together with their friends theologians Friedrich Strauß and Wilhelm Budde they joined in the “Eleusinischer Bund” and exchanged their poems. His first publication appeared under the pseudonym “Florens“, it was the publication of some poems in Ast’s “Zeitschrift für Wissenschaft und Kunst” (Journal of Science and Art). Around this time he also began to write down the fairy tale novella Die Zauberei im Herbste. (Magic in the Autumn) In November 1809 Eichendorff travelled with his brother to Berlin, where he heard private lectures by Fichte [2] and met Arnim, Brentano and Kleist.[3] In the summer of 1810 he continued to study law in Vienna and graduated in 1812.

Divining Rod (1835)

A song sleeps in all things,

Which dream on and on,

And the world begins to sing,

If only you find the magic word.

Napoleonic Liberation Wars and the Loss of a Childhood’s World

From 1813 to 1815 Eichendorff took part in the wars of liberation against Napoleon, first as a hunter from Lützow, then as a lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion of the 17th Silesian Landwehr Infantry Regiment in the devastated fortress of Torgau and finally again, after his marriage, in the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Rhineland Landwehr Infantry Regiment on his entry into Paris. He remained with the occupying troops until the end of 1815 and did not return to Breslau until the following year. In April 1815 Eichendorff had married Luise von Larisch in Breslau. After the death of Eichendorff’s father in 1818, most of the family’s highly indebted estates were sold except for Schloss Lubowitz and the Sedlnitz estate. Eichendorff mourned the loss of his childhood’s world all his life.

Moonlit Night (1837)

It was as if heaven

Had silently kissed the earth,

So that she in shimmering blossoms

Must now dream of him.

Eichendorff’s Later Years

After Eichendorff had begun his Prussian civil service in 1816 as an articled clerk in Breslau, he was appointed Catholic Church and School Councillor in Gdansk in 1821 and Senior President Councillor in Königsberg in 1824. In 1831 the family moved to Berlin, serving several Prussian ministries. In 1841 Eichendorff was appointed Privy Councillor. After a severe pneumonia in 1843 he retired in 1844. In 1846 he translated some of Pedro Calderón de la Barca‘s religious dramas. From 1856 to 1857 Eichendorff was a guest of Prince-Bishop Heinrich Förster of Wroclaw at Johannisberg Castle near Jauernig, where he also worked as a writer. Eichendorff finished his literary work in the last decade of his life and instead became active in journalism. During this time he wrote his “History of Poetic Literature“.

Eichendorff died of pneumonia on 26 November 1857 at the age of 69.

Eichendorff’s Literary Work

Eichendorff is counted among the most important and still today admired German writers. Many of his poems have been set to music and sung many times. His novella Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts (From the life of a good-for-nothing) is regarded as the climax and at the same time the end of Romanticism. This is the story: a miller sends his son away, calling him a good-for-nothing. The young man takes his fiddle along and leaves happily, without a specific destination. Soon two ladies in a carriage, who are interested in his music, take him along to their palace close to Vienna, where he gets a job as a gardener. He falls in love with the younger lady. Promoted to tax collector, he plants flowers in the garden of the tax house instead of potatoes, placing them regularly for his beloved. He plans to make money, but when he sees his beloved with an officer, he realizes that she is not available for him and leaves. Further travel takes him to Italy, with adventures on the way and in Rome. Back at the palace, several mysteries about identities are revealed, and he can marry his beloved Aurelie, who is not a noble woman but an orphan.

![Joseph von Eichendorff, Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts, from [11]](http://scihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/taugenichts02-650x573.jpg)

Joseph von Eichendorff, Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts, from [11]

Seeking European Coexistence

Eichendorff’s idyllic depictions of nature and simple life are characterised by simple imagery and choice of words. Behind them, however, is a multi-layered web of metaphorical symbolism for the interpretation of world, nature and soul, which stands out from pure utility thinking (Eichendorff wrote in the age of the beginning industrial revolution). A typical feature of many of Eichendorff’s works is that they are often religiously related due to his own strong attachment to the faith. Unlike Clemens Brentano, however, Eichendorff’s Catholicism was neither marked by torments of the soul nor by a particular missionary zeal. It is also noteworthy that – unlike so many other Romantics under Fichte’s influence – he did not fall for nationalistic Germanomania, which downgraded other peoples, but sought European coexistence. Eichendorff’s poetry of this period (Gedichte, 1837), particularly the poems expressing his special sensitivity to nature, gained the popularity of folk songs and inspired such composers as Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Richard Strauss.[6] Eichendorff summed up the Romantic epoch stating that it “soared like a magnificent rocket sparkling up into the sky, and after shortly and wonderfully lighting up the night, it exploded overhead into a thousand colorful stars.”

Jonathan Bate, The Origins of Romanticism, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Achim von Arnim – Forerunner of German Romanticism, SciHi Blog

- [2] Johann Gottlieb Fichte and the German Idealism, SciHi Blog

- [3] The Murder-Suicide of Heinrich von Kleist, SciHi Blog

- [4] German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Joseph von Eichendorff

- [5] Works by or about Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff at Internet Archive

- [6] Joseph, Baron von Eichendorff, German writer, at Britannica Online

- [7] Joseph von Eichendorff: Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts (in German), Book Review at Biblionomicon, Sep 12, 2008

- [8] Joseph von Eichendorff at Wikidata

- [9] Jonathan Bate, The Origins of Romanticism, Gresham College @ youtube

- [10] Hermann Kunisch: Eichendorff, Joseph Carl Benedikt Freiherr von. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0, S. 369–373

- [10] Timeline for Joseph von Eichendorff, via Wikidata