John Bunyan (1628-1688)

Probably on November 28, 1628, English writer and Puritan preacher John Bunyan was born. Bunyan is best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress. In addition to The Pilgrim’s Progress, is regarded as one of the most significant works of religious English literature, Bunyan wrote nearly sixty titles, many of them expanded sermons.

Early Years

John Bunyan was born in the parish of Elstow, Bedfordshire, UK, to Thomas and Margaret Bunyan at Bunyan’s End. Bunyan’s date of birth is not exactly known, but he was baptized on 30 November 1628. As a child Bunyan learned his father’s trade of tinker and was given some rudimentary schooling. In autumn 1644, shortly before or after his sixteenth birthday, Bunyan enlisted in the Parliamentary army when an edict demanded 225 recruits from the town of Bedford during the first stage of the English Civil War.

Becoming a Nonconfirmist Preacher

Bunyan’s army service provided him with a knowledge of military language which he then used in his book The Holy War, and also exposed him to the ideas of the various religious sects and radical groups he came across in Newport Pagnell. In 1647, Bunyan returned to Elstow and his trade as a tinker. At that time the nonconformist group was meeting in St John’s church in Bedford under the leadership of former Royalist army officer John Gifford. At the instigation of other members of the congregation Bunyan began to preach, both in the church and to groups of people in the surrounding countryside.

Bunyan’s conversion to Puritanism was a gradual process in the years following his marriage (1650–55); it is dramatically described in his autobiography. After an initial period of Anglican conformity in which he went regularly to church, he gave up, slowly and grudgingly, his favorite recreations of dancing and bell ringing and sports on the village green and began to concentrate on his inner life. Then came agonizing temptations to spiritual despair lasting for several years. The Bedford community practiced adult Baptism by immersion, but it was an open-communion church, admitting all who professed “faith in Christ and holiness of life.” Bunyan soon proved his talents as a lay preacher.[1]

Restauration

The religious tolerance which had allowed Bunyan the freedom to preach became curtailed with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The members of the Bedford Meeting were no longer able to meet in St John’s church, which they had been sharing with the Anglican congregation. In November 1660, Bunyan was preaching at Lower Samsell, a farm near the village of Westoning, thirteen miles from Bedford, when he was warned that a warrant was out for his arrest. Deciding not to make an escape, he was arrested and brought before the local magistrate. Bunyan was arrested under the Conventicle Act of 1593, which made it an offense to attend a religious gathering other than at the parish church with more than five people outside their family.

Trial and Imprisonment

The trial of Bunyan took place in January 1661 before a group of magistrates under John Kelynge, who would later help to draw up the Act of Uniformity. Bunyan, who had been held in prison since his arrest, was indicted of having “devilishly and perniciousy abstained from coming to church to hear divine service” and having held “several unlawful meetings and conventicles, to the great disturbance and distraction of the good subjects of this kingdom“. He was sentenced to three months imprisonment with transportation to follow if at the end of this time he didn’t agree to attend the parish church and desist from preaching. As Bunyan refused to agree to give up preaching, his period of imprisonment eventually extended to 12 years and brought great hardship to his family. His second wife Elizabeth, who made strenuous attempts to obtain his release, had been pregnant when her husband was arrested and she subsequently gave birth prematurely to a still-born child. Left to bring up four step-children, one of whom was blind, she had to rely on the charity of Bunyan’s fellow members of the Bedford Meeting and other supporters and on what little her husband could earn in gaol by making shoelaces.

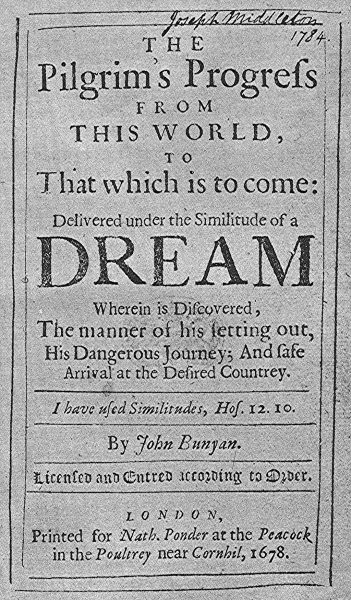

Pilgrim’s Progress, first edition 1678

The Pilgrim’s Progress

In Bunyan’s 12 years of imprisonment, there were however occasions when he was allowed out of prison, depending on the gaolers and the mood of the authorities at the time, and he was able to attend the Bedford Meeting and even preach. In prison, Bunyan had a copy of the Bible and of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, as well as writing materials. It was there, where he wrote Grace Abounding and started work on The Pilgrim’s Progress, as well as penning several tracts that may have brought him a little money. In 1671, while still in prison, he was chosen as pastor of the Bedford Meeting. By that time there was a mood of increasing religious toleration in the country and in March 1672 the king issued a declaration of indulgence which suspended penal laws against nonconformists. Thousands of nonconformists were released from prison, amongst them Bunyan, who immediately obtained a license to preach under the declaration of indulgence.

Further Literary Achievements

Following his release from gaol in 1672 Bunyan probably did not return to his former occupation of tinker. Instead he devoted his time to writing and preaching. He continued as pastor of the Bedford Meeting and travelled over Bedfordshire and adjoining counties on horseback to preach, becoming known affectionately as “Bishop Bunyan”. Bunyan’s principal fictional works were published during the post-imprisonment period: the two parts of The Pilgrim’s Progress in 1678 and 1684, The Life and Death of Mr. Badman in 1680, and The Holy War in 1682. Most of the rest of Bunyan’s sixty publications were doctrinal and homiletic in nature.[2] In 1676-7 he underwent a second term of imprisonment, probably for refusing to attend the parish church, which lasted six months.

Bunyan’s literary achievement, in his finest works, is by no means that of a naively simple talent, as has been the view of many of his critics. His handling of language, colloquial or biblical, is that of an accomplished artist. He brings to his treatment of human behavior both shrewd awareness and moral subtlety, and he demonstrates a gift for endowing the conceptions of evangelical theology with concrete life and acting out the theological drama in terms of flesh and blood.[1] Bunyan’s great allegorical tale The Pilgrim’s Progress recapitulates in symbolic form the story of Bunyan’s own conversion, there is an intense, life-or-death quality about Christian’s pilgrimage to the Heavenly City in the first part of the book. This sense of urgency is established in the first scene as Christian in the City of Destruction reads in his book (the Bible) and breaks out with his lamentable cry, “What shall I do?” It is maintained by the combats along the road with giants and monsters such as Apollyon and Giant Despair, who embody spiritual terrors. The voices and demons of the Valley of the Shadow of Death are a direct transcription of Bunyan’s own obsessive and neurotic fears during his conversion.[1]

In 1688, on his way to London, Bunyan made a detour to Reading, Berkshire, to try and resolve a quarrel between a father and son. Continuing to London to the house of his friend, grocer John Strudwick of Snow Hill in the City of London, he was caught in a storm and fell ill with a fever. He died in on the morning of 31 August 1688, aged 59.

Bob Ahlersmeyer, Enlightenment Era: John Bunyan – Pilgrim’s Progress (Lecture), [5]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] John Bunyan, English author, at Britannica Online

- [2] John Bunyan at The Poetry Foundation

- [3] Works by John Bunyan at Project Gutenberg

- [4] John Bunyan at Wikidata

- [5] Bob Ahlersmeyer, Enlightenment Era: John Bunyan – Pilgrim’s Progress (Lecture), Bob Ahlersmeyer @ youtube

- [6] Works by or about John Bunyan at Internet Archive

- [7] Moot Hall Elstow, a Museum specialising in 17th century life and John Bunyan

- [8] Brittain, Vera (1950). In the Steps of John Bunyan: An Excursion into Puritan England. London: Rich and Cowan.

- [9] Shears, Johnathon (2018). “Bunyan and the Romantics”. In Michael Davies and W. R. Owens, eds. The Oxford Handbook to John Bunyan. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- [10] Newspaper clippings about John Bunyan in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [11] Timeline of English theologian writers, via Wikidata