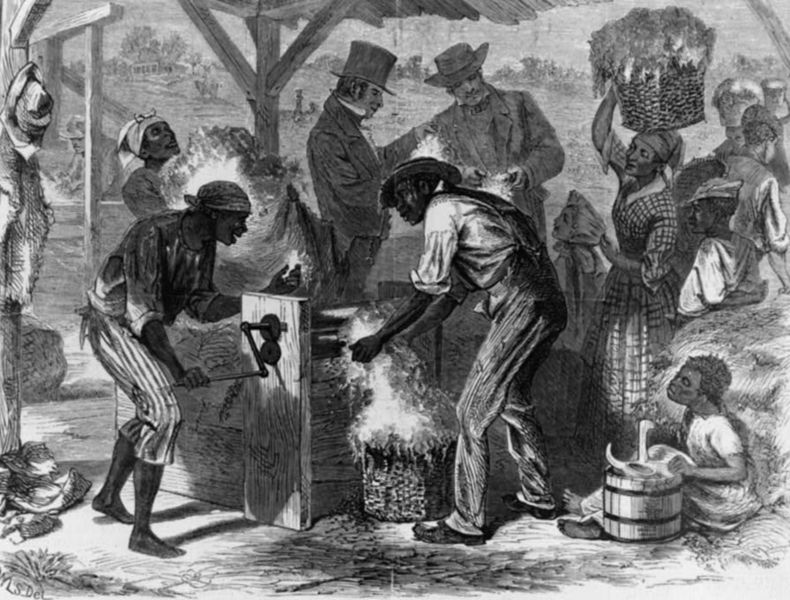

Eli Witney’s Cotton Gin used by African Americans slaves

On December 8, 1765, American inventor Eli Whitney was born. Whitney is best known for inventing the cotton gin. This was one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution and shaped the economy of the Antebellum South. Whitney’s invention made upland short cotton into a profitable crop, which strengthened the economic foundation of slavery in the United States.

“As Arkwright and Whitney were the demi-gods of cotton, so prolific Time will yet bring an inventor to every plant. There is not a property in nature but a mind is born to seek and find it.”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, in Fortune of the Republic (1878), 3.

Eli Whitney – Early Years

Eli Whitney was born in Westborough, Massachusetts, on December 8, 1765, the eldest child of Eli Whitney Sr., a prosperous farmer, and his wife Elizabeth Fay, also of Westborough. At age 14 he already operated a profitable nail manufacturing operation in his father’s workshop during the Revolutionary War. His wish to attend college was opposed by his stepmother and Whitney then worked as a farm laborer and school teacher to save money. At Leicester Academy (now Becker College), Whitney prepared for Yale University. He graduated in 1792 and expected to study law but finding himself short of funds then accepted an offer to go to Georgia, South Carolina as a private tutor. However, on his way to South Carolina, Whitney met the widow and the family of the Revolutionary hero General Nathanael Greene of Rhode Island. He was invited to their plantation Mulberry Grove, where he met the plantation manager Phineas Miller, another Connecticut migrant, who would become Whitney’s business partner.

Eli Whitney (December 8, 1765 – January 8, 1825)

The Cotton Gin

Eli Whitney is best known for inventing the cotton gin. Cotton fibers are produced in the seed pods of the cotton plant where the fibers in the bolls are tightly interwoven with seeds. The seeds and fibers must first be separated, a task which had been previously performed manually, with production of cotton requiring hundreds of hours of labor for the separation. Many simple seed-removing devices had been invented, but until the innovation of the cotton gin, most required significant operator attention and worked only on a small scale. The first documentation of the cotton gin by contemporary scholars is found in the fifth century A.D., in the form of Buddhist paintings depicting a single-roller gin in the Ajanta Caves in western India. However, earlier cotton gins were difficult to use and required great skill.

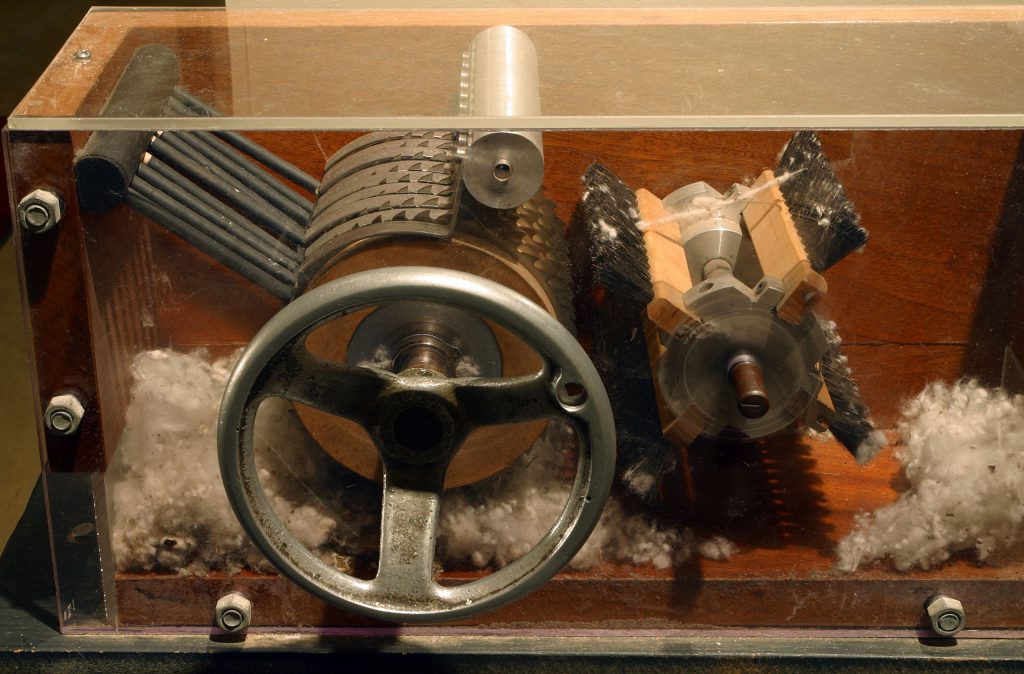

A cotton gin on display at the Eli Whitney Museum.

Eli Whitney applied for his cotton gin patent in 1793 and it was granted in March 1794. However, it is not clear until this day to which extent Catherine Littlefield Greene contributed to the development of the engine and it is assumed that she suggested the use of a brush-like component instrumental for separating out the seeds and cotton.

The cotton gin, developed by Whitney was capable of cleaning 23 kg of lint a day. His model consisted of a wooden cylinder surrounded by rows of slender spikes, which pulled the lint through the bars of a comb-like grid. Many contemporary inventors attempted to develop a design that would process short staple cotton, and Hodgen Holmes, Robert Watkins, William Longstreet, and John Murray had all been issued patents for improvements to the cotton gin by 1796. However, it is believed that Whitney invented the saw gin, for which he is famous.

Economic Consequences

The cotton gin transformed Southern agriculture and the national economy. Southern cotton found ready markets in Europe and in the burgeoning textile mills of New England. Cotton exports from the U.S. boomed after the cotton gin’s appearance – from less than 500,000 pounds (230,000 kg) in 1793 to 93 million pounds (42,000,000 kg) by 1810. Cotton was a staple that could be stored for long periods and shipped long distances, unlike most agricultural products. It became the U.S.’s chief export, representing over half the value of U.S. exports from 1820 to 1860. It has further been argued that Whitney’s cotton gin was an important if unintended cause of the American Civil War. After Whitney’s invention, the plantation slavery industry was rejuvenated, eventually culminating in the Civil War.

Later Years

Although Whitney’s ideas were inventive and useful, many others deliberately copied the concepts and designs. Whitney’s company ran into considerable difficulties in 1797. He never patented his more recent inventions, such as a milling machine. Towards the end of 1790, Eli Whitney Jr. was in debt and on his way to bankruptcy. His factory in New Haven also burned down. The American government gave him a new chance and concluded a contract with him in 1798 for the supply of 10,000 muskets. Whitney, who had never manufactured weapons, developed the principle of standardized production of interchangeable parts and defended it until his death of prostate cancer in 1825 at age 59.

King Cotton (1949), [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Eli Whitney at Britannica

- [2] Eli Whitney Information Webpage

- [3] The Story of Cotton – National Cotton Council of America site

- [4] Lakwete, Angela (2003). Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- [5] Eli Whitney at Wikidata

- [6] “Whitney, Eli“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 611.

- [7] Obituary for Eli Whitney, in Niles Weekly Register, January 25, 1825

- [8] Inventor of the Week: Eli Whitney (MIT)

- [9] “King Cotton”, movie produced by Jam Handy (1949), via YouTube

- [10] Dexter, Franklin B. (1911). “Eli Whitney.” Yale Biographies and Annals, 1792–1805. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Company.

- [11] American inventors of the Antebellum period, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #17 | Whewell's Ghost