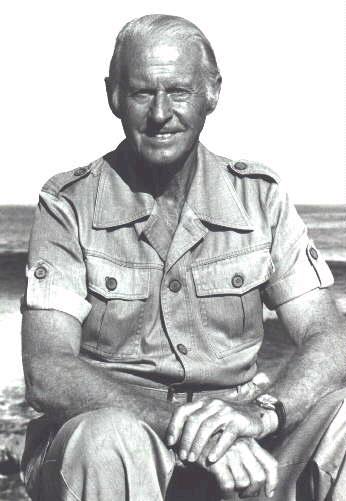

Thor Heyerdahl (1914 – 2002)

On April 28, 1947, Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer Thor Heyerdahl and five crew mates set out from Peru on the self-built raft Kon-Tiki to prove that Peruvian natives could have settled Polynesia. With Kon-Tiki, Heyerdahl sailed 8,000 km across the Pacific Ocean in a self-built raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands to demonstrate that ancient people could have made long sea voyages, creating contacts between apparently separate culture.

Thor Heyerdahl Background

Thor Heyerdahl studied zoology, geography, and anthropology at the University of Oslo. In 1940, he participated in a expedition to British Columbia and noticed significant similarities with Polynesia. Also, during a stay on Fatu Hiva, he noticed that certain statues reminded him of those in South America. Due to his observations and the fact that many researchers have made similar observation, Heyerdahl made the hypothesis that it was possible to travel from North America to Polynesia with a small single boat.

To prove his hypothesis, Thor Heyerdahl decided to build a small raft and travel all the way by himself guided by five crew members consisting of a cook, an engineer, a helms person and two radio operators.

Expedition Kon-Tiki 1947. Across the Pacific. Nasjonalbiblioteket from Norway

The Raft

The raft itself was built from 60 cm thick balsa wood connected with hemp rope. The construction was supported with pine wood and the mast consisted of two almost 9m long pieces of mangrove wood. They decided not to use any metal pieces in order to guarantee a solid experiment. The modern equipment was limited to the radio equipment, a rubber dinghy, survival equipment as well as navigation equipment and a film camera to document the experiment, which was also intended to provide information on survival at sea. In addition to fresh food such as coconuts, canned food and a plankton net were also carried. However, the crossing proved that the participants had survived from fishing alone. The documentary about the expedition was awarded an Academy Award.

The Expedition

From Callao, Peru, the crew left and sailed straight to the Humboldt current. Controlling the “ship” was difficult at first, because the crew had to learn sailing techniques of the Native Americans. On their trip, the six men caught fish, and collected rain water, saving their own stock. On July 30, the Kon-Tiki reached Puka-Puka, but was unable to berth. Only 7 days later, the raft run aground near Raroia after a journey of 101 days and 6980 km.

The Kon-Tiki had 1100 litres of drinking water in 56 water cans on board. As provisions 200 coconuts, sweet potatoes, bottle gourds and other fruits as well as root vegetables served. The US Army provided food rations, cans and survival equipment. However, it turned out that the crew would also have survived from fishing and possible provisioning at the time. Flying fish, dolphinfish, yellowfin tuna and sharks were caught.

In the passat zone, rainwater could be collected and drinking water supplies supplemented. Shortwave radio enabled regular contact with radio amateurs, especially in the USA. On July 30, the atoll Puka-Puka came into sight for the first time, but could not be started due to lack of manoeuvrability: The raft drifted by. Landing on Fangatau on 4 August was also not possible. Three days later, on August 7th, the raft hit the reef off Raroia in the Tuamotu archipelago before the wind. It had covered around 3,770 nm (6,980 km) in 101 days at an average speed of 1.5 knots.

The Kon-Tiki structures were damaged during the landing (the hut collapsed), but the nine main tribes of the raft remained intact. The crew went ashore and was discovered after a week by Polynesians living on the other side of the atoll. The raft was soon flushed into the lagoon at a higher tide level across the reef. It was then towed to Tahiti and brought back to Norway with the help of Norwegian shipowners, where the Kon-Tiki Museum was built in Oslo.

Discoveries of the Kon-Tiki Expedition

Next to Heyerdahl’s extraordinary accomplishment, almost proving his hypothesis and safely reaching Polynesia, the crew made several discoveries during their trip. They for instance discovered several fish kinds, like the snake mackerels. However, the final prove of Heyerdahl’s hypothesis is still not given. He did indeed demonstrate, that a journey across the Pacific Ocean with simple rafts was possible but he could not show that in fact this ever happened in history. Anthropologists continue to believe that Polynesia was settled from west to east, based on linguistic, physical, and genetic evidence, migration having begun from the Asian mainland. There are controversial indications, though, of some sort of South American/Polynesian contact, most notably in the fact that the South American sweet potato is served as a dietary staple throughout much of Polynesia.

At the moment several scientific theories circulate in the scientific community, but since none could be completely proven, the Polynesian origin remains unknown.

How did Polynesian wayfinders navigate the Pacific Ocean? – Alan Tamayose and Shantell De Silva, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Kon-Tiki Museum Website

- [2] Thor Heyerdahl Expeditions

- [3] How the Voyage of the Kon-Tiki Misled the World About Navigating the Pacific at Smithsonian

- [4] Thor Heyerdahl at Wikidata

- [5] Wilford, John Noble (19 April 2002). “Thor Heyerdahl Dies at 87; His Voyage on Kon-Tiki Argued for Ancient Mariners”. The New York Times

- [6] Sea Routes to Polynesia Extracts from lectures by Thor Heyerdahl

- [7] Thor Heyerdahl – Daily Telegraph obituary

- [8] How did Polynesian wayfinders navigate the Pacific Ocean? – Alan Tamayose and Shantell De Silva, TED-Ed @ youtube

- [9] Testing Heyerdahl’s Theories about Kon-Tiki 60 Years Later: Tangaroa Pacific Voyage (Summer 2006) Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:4 (Winter 2006)

- [10] Thor Heyerdahl, Thor (1968). The Kon-Tiki Expedition. Rand McNally.

- [11] Timeline or Thor Heyerdahl, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #46 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol: #38 | Whewell's Ghost