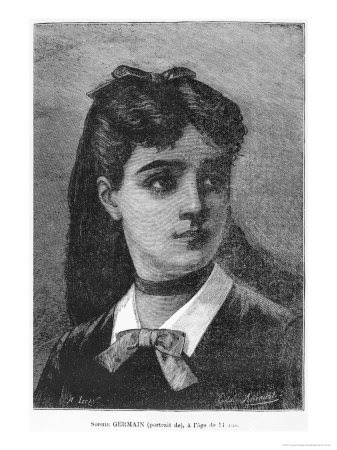

Sophie Germain (1776 – 1831)

On June 27, 1831, French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher Marie-Sophie Germain passed away. She is best known for her work in number theory and contributions to the applied mathematics of acoustics and elasticity. Her work on Fermat’s Last Theorem provided a foundation for mathematicians exploring the subject for hundreds of years after. Because of prejudice against her gender, she was unable to make a career out of mathematics, but she worked independently throughout her life.

“Algebra is but written geometry and geometry is but figured algebra.”

— Sophie Germain, From Mémoire sur les Surfaces Élastiques. As quoted in [14]

Sophie Germaine – Youth and Education

There is not much known about Sophie Germain’s early life. Many historians believe that she was the daughter of a pretty wealthy silk merchant while others assume, her father used to be a goldsmith. Clear is however, that she was born in 1776 in Paris. When the French Revolution started in France, Germain was 13 years old and it is widely assumed that she had to stay inside due to safety reasons and that she spent a lot of time in her father’s library to keep herself entertained. However, Sophie read an account of the death of Archimedes at the hands of a Roman soldier and was so moved by this story that she decided she too must become a mathematician.[5] Among the books that attracted her interest the most was apparently J. E. Montucla’s “L’Histoire des Mathématiques“. Next to mathematics, the young woman also started to teach herself in Greek and Latin in order to understand the works of Newton and Euler. Furtherly, it is believed that Germain studied “Le Calcul Différentiel” by Jacques Antoine-Joseph Cousin, who highly encouraged her in her studies during a visit. However, it is widely assumed that Germain had lots of trouble convincing her parents from her new passions, who first did not approve her studies and apparently even took away her materials until realizing that she was really serious about it.

Lagrange, Legendre, and Gauss

“In describing the honourable mission I charged him with, M. Pernety informed me that he made my name known to you. This leads me to confess that I am not as completely unknown to you as you might believe, but that fearing the ridicule attached to a female scientist, I have previously taken the name of M. LeBlanc in communicating to you those notes that, no doubt, do not deserve the indulgence with which you have responded.”

— Sophie Germain, Letter to Carl Friedrich Gauss (1807), Explaining her use of a male psuedonym.

When the École Polytechnique opened, Sophie Germain was about 18 years old and of course, as a woman not allowed to attend any courses. However, she managed to study the lecture notes and started sending own works to the faculty member Joseph Louis Lagrange [7] under the name of a former student. When Lagrange requested a meeting with the student, her real identity was revealed and luckily, the scientist became her mentor, impressed by Germain’s brilliance. Soon, she started corresponding with Adrien-Marie Legendre [8] in order to discuss number theory and later on also elasticity. Also the well established mathematician published some of her work in a later edition of the “Théorie des Nombres“. In this period, Sophie Germain also started corresponding with Gauss, again under pseudonym, who admired her courage and intelligence. During their correspondence, Gauss gave her number theory proofs high praise, an evaluation he repeated in letters to his colleagues. Germain’s true identity was revealed to Gauss only after the 1806 French occupation of his hometown of Braunschweig. Recalling Archimedes’ fate and fearing for Gauss’s safety, she contacted a French commander who was a friend of her family. When Gauss learnt that the intervention was due to Germain, he gave her even more praise.[4]

Ernst Chladni and the Vibrations of Elastic Surfaces

However, at some point, Gauss and Germain’s correspondence stopped and she became more and more interested in the Ernst Chladni and his experiments. The German scientist is probably best known for his research on vibrating plates and the calculation of the speed of sound for different gases. Germain heard of a contest sponsored by the Paris Academy of Sciences concerning Chladni’s experiments with vibrating metal plates and the goal was “to give the mathematical theory of the vibration of an elastic surface and to compare the theory to experimental evidence“.

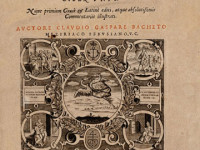

Récherches sur la théorie des surfaces élastiques, 1821

The Struggle for the Prize of the Paris Academy

Lagrange then commented that a solution to the problem would require the invention of a new branch of analysis and thus, Germain became the only person to enter the competition. After having submitted her paper in 1811, Germain did not win the prize even though “the experiments presented ingenious results“. After two more extensions of the competition, Germain consulted the judge Denis Poisson, who shortly after published his own research results on elasticity, not mentioning Germain’s help in any sentence. When Sophie Germain submitted her third work on the topic in 1816, she became the first woman to win a prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences even though the judges were again not completely satisfied as her method was not believed to be accurate enough and relied on incorrect equations from Euler. However, even though she had won the prize, Germain was still not able to attend the Academy’s sessions as a woman until two years later, the befriended Joseph Fourier acquired tickets for her.

Death

In 1829 Germain learned she had breast cancer. Despite the pain, she continued to work. In 1831 Gauss advocated that the University of Göttingen confer an honorary doctorate on her. However, this did not happen anymore. Sophie Germain died on 27 June 1831, at age 55. Her death certificate listed her not as mathematician or scientist, but rentier (property holder).[4] At the centenary of her life, a street and a girls’ school were named after her. The Academy of Sciences established the Sophie Germain Prize in her honor.

Sophie Germain – The Forgotten Woman of the Eiffel Tower, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Biography of Marie-Sophie Germain

- [2] Sophie Germain at Britannica

- [3] Sheroes of History – Sophie Germain

- [4] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Sophie Germain“, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- [5] Sophie Germaine at Wikidata

- [6] Sophie Germain at zbMATH

- [7] Joseph-Louis Lagrange and the Celestial Mechanics, SciHi Blog

- [8] Legendre’s Elements of Geometry, SciHi Blog

- [9] Andrea del Centina Letters of Sophie Germain in Florence

- [10] Sophie Germain at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [11] Sophie Germain – The Forgotten Woman of the Eiffel Tower, Matematickcom Official @ youtube

- [12] Merow, Sophia D. (September 2019). “One Spark Is All You Need: Germain Gets the Hamilton Treatment”. Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 66 (8): 1309–1311.

- [13] Del Centina, Andrea (2005). “Letters of Sophie Germain preserved in Florence”. Historia Mathematica. 32 (1): 60–75.

- [14] Robert Édouard Moritz, Memorabilia Mathematica; Or, The Philomath’s Quotation-book (1914), 276.

- [15] Gray, Mary (1978). “Sophie Germain (1776–1831)”. In Louise S. Grinstein; Paul Campbell (eds.). Women of Mathematics: A Bibliographic Sourcebook. Greenwood. pp. 47–55

- [16] Timeline of Women Physicists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #46 | Whewell's Ghost