Michel de Nostredame (1503-1566)

On May 4, 1555, The first edition of Michel de Nostredame‘s (usually Latinized as Nostradamus) ‘Les Propheties‘, a famous collection of long-term predictions that have since become famous worldwide, was published.

“Perfect knowledge of such things cannot be acquired without divine inspiration, given that all prophetic inspiration derives its initial origin from God Almighty, then from chance and nature.”

— Michel de Nostredame, Les Propheties (1555)

Very little is known about Michel de Notredame’s Youth

Born on December 14 or 21, 1503 in Saint-Remy-de-Provence in the south of France, where his claimed birthplace still exists, Michel de Nostredame was one of at least nine children grain dealer and notary Jaume de Nostredame and his wife of Reyniere de Saint-Remy. His father’s family had originally been Jewish, but Jaume’s father, Guy Gassonet, had converted to Catholicism around 1455, taking the Christian name “Pierre” and the surname “Nostredame”. Very little is known about Michel’s childhood. At the age of 15 he entered the University of Avignon, France, a major ecclesiastical (church related) and academic center, to study for his baccalaureate, but after his first year at the university, he was forced to leave Avignon when the university closed its doors in the face of an outbreak of the plague.

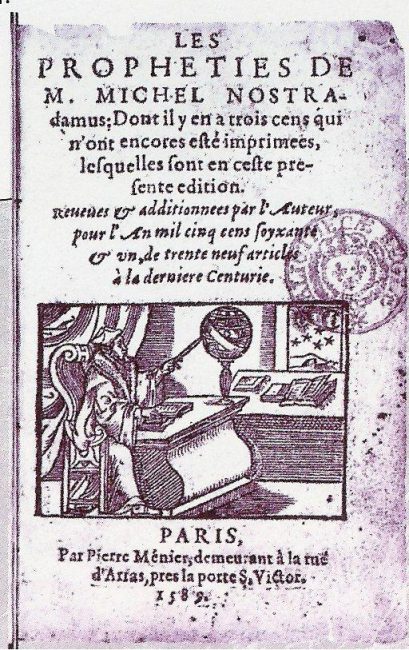

An edition of Nostradamus Centuries from the year 1589

The Plague Pandemic and the Rose Pill

The plague pandemic, also referred to as the Black Death, likely began in Asia in the 14th century and spread to Europe, where repeated outbreaks decimated the populations of various countries through the 17th century. The disease, which was transmitted through fleas and rodents, was highly contagious, fast-acting and painful, often causing delirium and leaving large black pustules all over a victim’s body. Because of the black sores, it was also called “Le Charbon” (“coal” or “carbon”). The epidemic had no cure. Having left Avignon in 1521, Nostredame travelled the countryside for eight years researching herbal remedies. Then, in 1529, after some years as an apothecary, he entered the University of Montpellier to study for a doctorate in medicine. But, he was expelled shortly afterwards, when it was discovered that he had been practicing as an apothecary, a “manual trade” expressly banned by the university statutes, and had been slandering doctors. Nostredame continued working, presumably still as an apothecary, and became famous for creating a “rose pill” that supposedly protected against the plague. Nostradamus also prescribed fresh air and water for the afflicted. He recommended a low-fat diet and clean bedding. Entire towns recovered under his care. Although his herbal remedies were common to the era, Nostredame’s beliefs about infection control, however, were contrary to the practices of his time.

Collaboration with Scaliger

In 1531 Nostredame was invited by Jules-César Scaliger,[6] a leading Renaissance scholar, to come to Agen, where he also married. But, in 1534 his wife and his two children died, presumably from the plague. After their deaths, he continued to travel, and other cities. Finally, in 1547, he settled in Salon-de-Provence and married a rich widow named Anne Ponsarde, with whom he had six children — three daughters and three sons. It was after a visit to Italy, when Nostredame began to move away from medicine and toward the occult. Following popular trends, he wrote an almanac for 1550, for the first time Latinizing his name from Nostredame to Nostradamus. He was so encouraged by the almanac’s success that he decided to write one or more annually. Taken together, they are known to have contained at least 6,338 prophecies, as well as at least eleven annual calendars. It was mainly in response to the almanacs that the nobility and other prominent persons from far away soon started asking for horoscopes and also “psychic” advice from him.

When twenty years of the Moon’s reign have passed

another will take up his reign for seven thousand years.

When the exhausted Sun takes up his cycle

then my prophecy and threats will be accomplished.

— Michel des Nostredame, Les Propheties (1555), Century 1, Q 48

Nostradamus’ Prophecies

His next project should become his opus magnum, a book of one thousand mainly French quatrains – a type of stanza, or a complete poem, consisting of four lines – which constitute the largely undated prophecies for which he is most famous today. However, he devised a method of obscuring his meaning by using word games and a mixture of other languages such as Greek, Italian, Latin, and also Provençal. The quatrains, published in a book titled Les Propheties (The Prophecies), received a mixed reaction when they were published. Some people thought Nostradamus was a servant of evil, a fake, or insane, while many of the elite thought his quatrains were spiritually-inspired prophecies. Catherine de’ Medici, wife of King Henry II of France, was one of Nostradamus’ greatest admirers. After reading his almanacs for 1555, which hinted at unnamed threats to the royal family, she summoned him to Paris to explain them and to draw up horoscopes for her children.

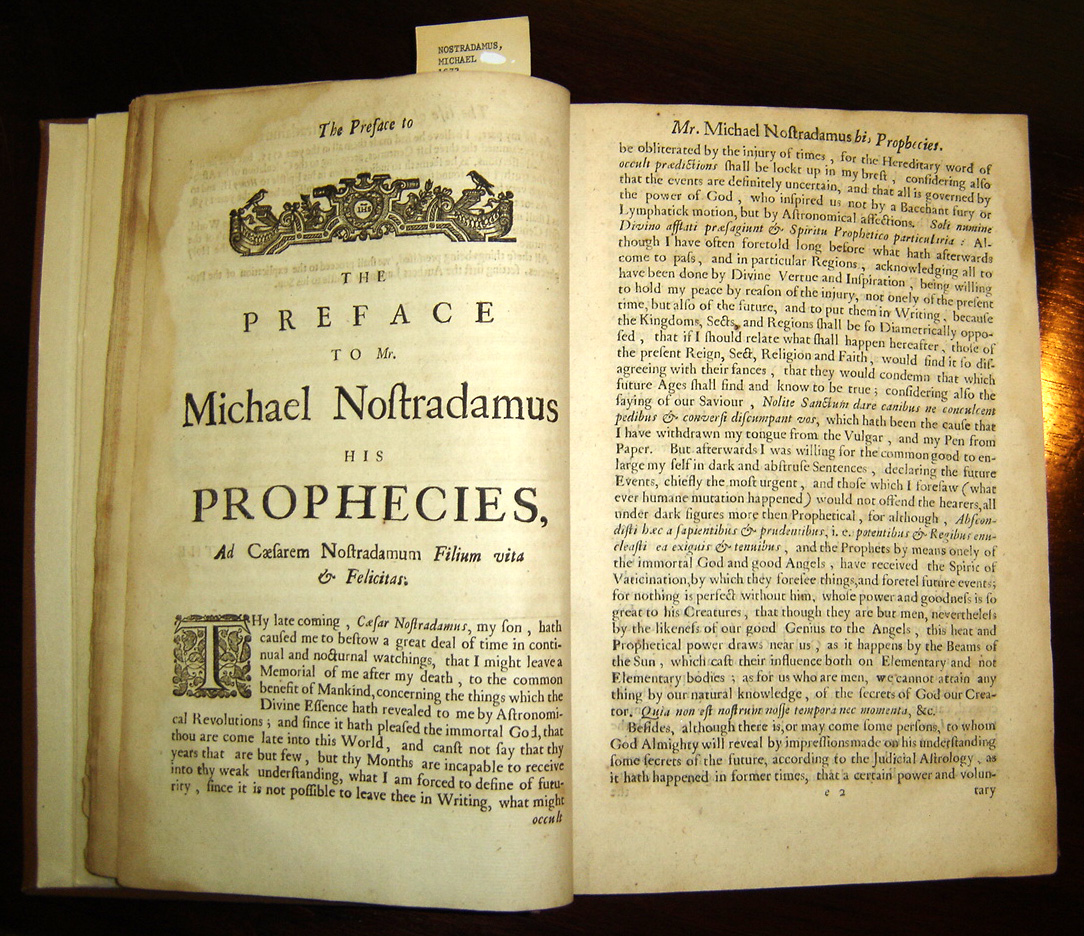

Copy of Theophilus de Garencières’ English translation of the Propheties of 1672, today in the P. I. Nixon Medical History Library of the University of Texas at San Antonio

Disasters, Earthquakes, and Murders

Given printing practices at the time (which included type-setting from dictation), no two editions of the Prophecies turned out to be identical, and it is relatively rare to find even two copies that are exactly the same. Certainly there is no warrant for assuming — as would-be “code-breakers” are prone to do — that either the spellings or the punctuation of any edition are Nostradamus’ originals. Most of the quatrains deal with disasters, such as plagues, earthquakes, wars, floods, invasions, murders, droughts, and battles — all undated and based on foreshadowings by the Mirabilis Liber, an anonymous and formerly very popular compilation of predictions by various Christian saints and divines that was published in France in 1522. A major, underlying theme is an impending invasion of Europe by Muslim forces from further east and south headed by the expected Antichrist.

Later Years

In 1564 – two years before his death – Nostradamus, now 60 years old and wealthy, is said to have been appointed the King’s personal physician on the occasion of a visit to Salon by the new King Charles IX and his mother Katharina. In the night from 1 to 2 July 1566, Nostradamus died at the age of 62 of a heart attack or asthma attack as a result of his dropsy, which he himself is said to have prophesied. In the confusion of the French Revolution in 1791, his grave was desecrated and his bones scattered by national guards from Marseille. Many translations of his Prophecies and treatises on their significance appeared in the generations following his death. They remain popular to the present day.

James Randi – Investigating Pseudoscientific and Paranormal Claims, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Nostradamus at History.com

- [2] Nostradamus at Britannica Online

- [3] Michel de Nostredame at notablebiographies.com

- [4] Reckless Power Play Politics – Niccolò Machiavelli, SciHi Blog, May 3, 2018

- [5] Nostradamus at Wikidata

- [6] Scaliger and the Science of Chronology, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works written by or about Nostradamus at Wikisource

- [8] James Randi – Investigating Pseudoscientific and Paranormal Claims, McGill University’s Lorne Trottier Public Science Symposium, Barry Belmont @ youtube

- [9] Randi, James (1990). The mask of Nostradamus. Scribner.

- [10] Gerson, Stéphane (2012). Nostradamus: How an Obscure Renaissance Astrologer Became the Modern Prophet of Doom. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- [11] Works by Nostradamus at LibriVox

- [12] Timeline of Prophets, via DBpedia and Wikidata

I an really thankful for this nice one post about “The Prophecies of Nostradamus”

For true Prophecy Of Nostradamus Click here: Prophecies of Nostradamus

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #18 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #38 | Whewell's Ghost