Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374), detail of a fresco by Andrea di Bartolo di Bargilla (c. 1450) Uffizi

On July 20, 1304, Italian scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) was born. He is considered to be one of the earliest humanists and also the “father of the Renaissance.” Petrarch’s sonnets were admired and imitated throughout Europe during the Renaissance and became a model for lyrical poetry. He is also known for being the first to develop the concept of the “Dark Ages”.

“I rejoiced in my progress, mourned my weaknesses, and commiserated the universal instability of human conduct.”

– Francesco Petrarca, Letter to Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro (26 April 1336)

Born in Tuscany

Born in Tuscany, Petrarca was influenced by important thinkers and poets like Dante Alighieri at very young age.[5] His father, the notary Pietro di Parenzo (surname: Petracco, Patraca) was banished from Florence as a papal pendant. At the age of seven Petrarca followed him to Avignon, where Pietro di Parenzo had lived since 1312, while his family lived in Carpentras. Petrarch studied law in Montpellier from 1316 and in Bologna from 1320. He returned to Avignon in 1326. He broke off his legal studies, received the lower ordinations and had his new domicile in a house in the area of today’s Vaucluse département. Petrarch chose the Church father Augustine as his role model and tried to emulate his way of life. After his father had died, Petrarca got into economic difficulties.[6]

Laura

On 6 April 1327, according to him a Good Friday, but in fact an Easter Monday, he saw a young woman whom he called Laura and who was possibly identical with Laura de Noves, then about 16 years old and married young. Her impression was so strong on him that he revered her throughout his life as the ideal female figure and permanent source of his poetic inspiration, knowing and accepting that she was unattainable to him. As a poet he strove for fame and laurels (Latin laurus) and found a means to do so in Laura.

Portrait of Laura de Noves, celebrated in his poetry by Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), Italian poet and humanist. Portrait in the Laurentian Library, Florence

“Laura […] appeared to my eyes for the first time in my first youth, in the year of the Lord 1327, on the sixth day of April, in the church of Saint Clare in Avignon […]. And in the same city, in the same month of April, also on the sixth day, at the same hour, but in the year 1348, that light has been withdrawn from the light of this world […].”

First Writings

He wrote numerous works after his studies were finished and to his first major and successful writing belongs Africa. The nine book epic poem was written in hexameters, a common form in classical Latin literature and poetry. In Africa, Petrarch told the story of the Second Punic War between the Romans and the Carthaginians, which made him famous all across Europe.

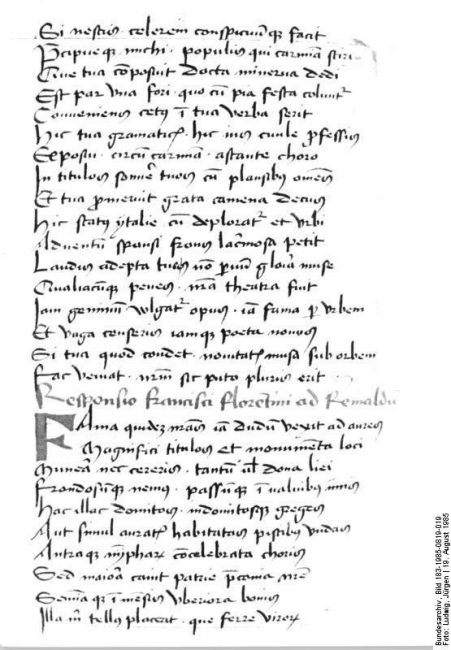

Original manuscript of a poem by Petrarch discovered in Erfurt in 1985

Mount Ventoux and the Beginning of the Renaissance

“To-day I made the ascent of the highest mountain in this region, which is not improperly called Ventosum. My only motive was the wish to see what so great an elevation had to offer.”

– Francesco Petrarca, Letter to Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro (26 April 1336)

Petrarch began traveling through Europe just for ‘fun’, which was the reason why he became also known as the first tourist. For about the same reason, the poet intended to climb the 2000 metres high Mont Ventoux, what he described in a letter dated 26 April 1336, written in Latin and addressed to the early humanist Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro. Petrarch was warned not to attempt reaching the summit, but it was no help. With him, he took a novel written by Saint Augustine, who was somewhat his mentor at this time. Passed on was a story, that when he reached the top, the book fell open, and ‘delivered’ Petrarch following words:

“And men go about to wonder at the heights of the mountains, and the mighty waves of the sea, and the wide sweep of rivers, and the circuit of the ocean, and the revolution of the stars, but themselves they consider not.“

These words opened his mind and caused some kind of epiphany to turn to his inner soul instead of the outer world. This moment of rediscovering the inner world during the descent of Mont Ventoux is now seen as the beginning of the Renaissance. The coincidence of experiencing nature and turning back to the self means a spiritual turning point, which Petrarch, concerning the experience of conversion, places in a row with Paulus of Tarsus, Augustine and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In contrast to medieval ideas, Petrarch no longer saw the world as a hostile and perishable one for man, which is only a transit station into a world beyond, but it now possessed its own value in his eyes. Some scholars therefore see the ascent of Mont Ventoux as a key cultural and historical moment on the threshold between the Middle Ages and modern times. In addition, Petrarch is considered the father of mountaineers and the founder of mountaineering because of this first “tourist” mountain ascent.

Later Years

The father of the Renaissance and the father of Humanism, Petrarca was the first to combine classical culture with Christian philosophy. In Secretum meum, he argued that God gave humans a great variety of intellectual and creative potential, which they could use to their own ‘preferences’. With his humanist philosophical ideas, he inspired the Renaissance and believed in the studies of ancient history and literature. After travelling through France, Belgium and Germany, Petrarch retreated to Fontaine-de-Vaucluse near Avignon, where he lived from 1337 to 1349 and wrote much of his Canzoniere. In 1341 Petrarch was crowned poet (poeta laureatus) on the Capitol in Rome. In between he went to the court of Cardinal Giovanni Colonna in Avignon, for eight years he was envoy in Milan. The last decade he lived alternately in Venice and Arquà.

“Hitherto your eyes have been darkened and you have looked too much, yes, far too much, upon the things of earth. If these so much delight you what shall be your rapture when you lift your gaze to things eternal!”

– Francesco Petrarca, Secretum Meum (1342), as translated in Petrarch’s Secret : or, The Soul’s Conflict with Passion : Three Dialogues Between Himself and St. Augustine (1911)

Petrarch the Poet

Next to his immense influence on contemporary philosophy, Petrarca is mostly known for his poetry. A major part of his works were written in Latin. To his most important belong De Viris Illustribus, an imaginary dialogue with Augustine of Hippo, De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae, a very popular of self help book and of course his unfinished epic Africa. He also published various letters, written to dead ‘friends’ from history like Cicero, Seneca or Virgil. Many of Petrarch’s works were set to music in the 16th century, which proves the great influence his writings had. About 1368 Petrarch and his daughter Francesca (with her family) moved to the small town of Arquà in the Euganean Hills near Padua, where he passed his remaining years in religious contemplation. Petrarch passed away on July 19, 1374 in his house in Arquà, which is now a permanent exhibition in honor to the poet.

Christopher S. Celenza, Jill Kraye, François Quiviger, Renaissance Lives | Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Petrarch Website

- [2] Petrarch in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- [3] Petrarch at the Middle Age Website

- [4] The works of Petrach at gutenberg.org

- [5] Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy, SciHi Blog

- [6] Saint Augustine’s Confessions, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works by or about Francesco Petrarca at Internet Archive

- [8] Poems From The Canzoniere, translated by Tony Kline.

- [9] Petrarch at Wikidata

- [10] Christopher S. Celenza, Jill Kraye, François Quiviger, Renaissance Lives | Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer, 2021, WarburgInstitute @ youtube

- [11] Rico, Francisco; Marcozzi, Luca (2015). “Petrarca, Francesco”. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 82. Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana.

- [12] “Petrarch (1304–1374) – the Complete Canzoniere: 184–244”. Poetryintranslation.com.

- [13] James, Paul (2014). “Emotional Ambivalence across Times and Spaces: Mapping Petrarch’s Intersecting Worlds”. Exemplaria. 26 (1): 81–104.

- [14] Hollway-Calthrop, Henry (1907). Petrarch: His Life and Times, Methuen.

- [15] Timeline for Francesco Petrarca, via Wikidata