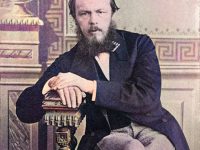

Ilya Repin’s celebrated portrait of Mussorgsky, painted 2–5 March 1881, only a few days before the composer’s death.

On March 21, 1831, Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky was born. Mussorgsky was an innovator of Russian music in the romantic period. He strove to achieve a uniquely Russian musical identity, often in deliberate defiance of the established conventions of Western music.

“My music must be an artistic reproduction of human speech in all its finest shades. That is, the sounds of human speech, as the external manifestations of thought and feeling must, without exaggeration or violence, become true, accurate music.”

Modest Moussorgsky, Letter to Lyudmila Shestakova, July 30, 1868;

Growing up in a Noble Family

Modest Mussorgsky was born in Karevo, Toropets Uyezd, Pskov Governorate, Russian Empire, as the youngest son into a wealthy and land-owning family, the noble family of Mussorgsky, which reputedly descended from the first Ruthenian ruler, Rurik. At age six Mussorgsky began receiving piano lessons from his mother, herself a trained pianist. His progress was sufficiently rapid and at age 10, he and his brother were taken to Saint Petersburg to study at the elite German language Petrischule with the noted Anton Gerke. In 1852, the 12-year-old Mussorgsky published a piano piece titled “Porte-enseigne Polka” at his father’s expense.

Cadet School in St Petersburg

Mussorgsky’s parents planned the move to Saint Petersburg so that both their sons would renew the family tradition of military service. To this end, in 1852 he entered the cadet school in St. Petersburg, where he was particularly interested in history and philosophy. He was also a member of the school choir there, and at the suggestion of his religion teacher, Father Krupski, he also dealt with Bortnianski and other Russian church music of the early 19th century. In 1856 he left the cadet school and joined the Preobraschensky regiment. During this time, he met Mili Balakirew, from whom he received his first formal instruction in music theory, which was essentially based on the great works of Ludwig van Beethoven,[6] Franz Schubert [7] and Robert Schumann.[8]

What to do?

The abolition of serfdom in the Russian tsarist empire in 1861 led his family into difficulties, so that he spent the next two years in the country to help his two brothers manage the family estate in Karevo. However, financial difficulties soon forced him to join the administrative service of the Czar. In 1863 he was appointed to the engineering department of the Ministry of Communications. After the publication of Chernyshevsky‘s novel What to do? new ideas had become popular in Russia, and during this time Mussorgski lived in a “community” with four other young men: Mili Balakirew, César Cui, Alexander Borodin and Nikolai Rimski-Korsakov, where he participated in the lively exchange of ideas on art, philosophy and politics. The group was ironically referred to as The Mighty Cluster or the Group of Five.

One Night on the Bald Mountain

After his release Mussorgski moved to the country with his brother, where he was particularly interested in orchestral works. The first version of his symphonic poem One Night on the Bald Mountain dates from this period. After returning to St. Petersburg, he began composing the opera Boris Godunov after a play by Pushkin. On 2 January 1869 he returned to the civil service, this time within the forestry department of the Ministry of State Property on February 8, 1874, his opera Boris Godunov finally premiered at the Mariinski theatre, who originally had refused and demanded changes.

Pictures of an Exhibition

In June 1874 he wrote the piano cycle Pictures at an Exhibition, which was inspired by an exhibition of drawings and stage designs by his deceased friend Viktor Hartmann. In 1878 Mussorgski moved from the forestry department to the auditing department, where he found an understanding superior in T. Filipov, who left him space for a three-month concert tour together with the alto Daria Leonova to Ukraine, Crimea and cities on Don and Volga. In the years that followed, Mussorgsky’s decline became increasingly steep. Although now part of a new circle of eminent personages that included singers, medical men and actors, he was increasingly unable to resist drinking, and a succession of deaths among his closest associates caused him great pain. At times, however, his alcoholism would seem to be in check, and among the most powerful works composed during his last six years are the four Songs and Dances of Death. On 13 January 1880 Mussorgsky had to leave the civil service because of his drunkenness, but was granted a pension of 100 rubles on condition that he completed his half-finished opera Khovanshina. However, the opera was never finished.

An Accompanist and Theory Teacher

During his last year of life he lived partly with Daria Leonova on her estate. He worked for her as an accompanist and theory teacher in the music school she founded in St. Petersburg. In early 1881 a desperate Mussorgsky declared to a friend that there was ‘nothing left but begging’, and suffered four seizures in rapid succession. Modest Mussorgsky died on March 28, 1881, one week after his 42nd birthday.

A Russian Romantic

Mussorgsky’s works, while strikingly novel, are stylistically Romantic and draw heavily on Russian musical themes. He has been the inspiration for many Russian composers, including most notably Dmitri Shostakovich (in his late symphonies) and Sergei Prokofiev (in his operas). However, most of Mussorgsky’s works were in unfinished condition at his death and after his death were edited and “corrected” by his friend Rimsky-Korsakov, according to the opera Khovanshina. The important piano work Pictures at an Exhibition has been orchestrated by several other composers; the most famous version is by Maurice Ravel.[9] Mussorgsky’s single-movement orchestral work Night on Bald Mountain enjoyed broad popular recognition in the 1940s when it was featured, in tandem with Schubert‘s ‘Ave Maria’, in the Disney film Fantasia.

Mussorgsky believed that speech itself followed strict musical rules and that music, like all art, is a means of communicating with people. He not only dealt in living scenes of real people but drew out of such situations certain principles and truths. And it is in the latter rather than the former that realism lies.[3]

Michael Parloff: Lecture on Russian Musical History, Part 1; Music@Menlo, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Modest Mussorgsky at Encyclopædia Britannica

- [2] Modest Moussorgsky at Biography.com

- [3] “Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. . Encyclopedia.com.

- [4] Modest Moussorgsky at BBC Music

- [5] Jeff Rouner, Modest Mussorgsky: History’s Most Trolled Composer, at Houston Press, March 23, 2011.

- [6] Probably the best known composer of the world – Ludwig van Beethoven,SciHi Blog, December 17, 2014.

- [7] Franz Schubert – Misjudged Pioneer of the Romantic Music, SciHi Blog, January 31, 2018.

- [8] The Romantic Music of Robert Schumann, SciHi Blog, June 8, 2016.

- [9] Maurice Ravel and Musical Impressionism, SciHi Blog, March 7, 2016.

- [10] Modest Mussorgsky at Wikidata

- [11] Michael Parloff: Lecture on Russian Musical History, Part 1; Music@Menlo, 2016, Michael Parloff @ youtube

- [12] Emerson, Caryl (1999). The Life of Musorgsky (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press

- [13] Timeline for Modest Mussorgsky, via Wikidata

Pingback: 10 Composer Hairstyles for 2019 - Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra