Marco Polo (1254 – 1324)

Around 1254 (according to some sources on September 15, 1254 [1]) Venetian merchant traveler Marco Polo was born. He is best known for his journeys to Central Asia and China, narrated in the book “Il Milione” (‘The Book of the Wonders of the World‘).

“I have not told half of what I saw.”

– Marco Polo, On his death-bed, when urged to retract “some of the seemingly incredible statements he made in his book”

Marco Polo – Family Background

The Polos were respected citizens of Venice, but did not belong to the upper classes. Marco Polo himself was referred to in the archives as nobilis vir (nobleman), a title of which Marco Polo was proud. The name Polo comes from the Latin Paul, and Polos can be traced in Venice since 971. According to an (unspecified) tradition, the family originally came from Dalmatia, among other places the city of Šibenik and the island Korčula were mentioned as possible places of origin. The Polos were merchants, and already the great uncle Marco commanded a merchant ship in Constantinople in 1168. At the time of Marco Polo’s birth, his father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo (also known as Maffio or Matteo), about whom little is otherwise known, were on a trading voyage in the East.

The Travels of Niccoló and Maffeo Polo

Marco Polo’s father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo set out on a journey in 1260 to sell precious stones on the lower reaches of the Volga. Via Constantinople they went to Soldaia (today Sudak) in Crimea, where Marco the Elder, the third of the Polo brothers, ran an office. Thus they traveled almost on the same route that William of Rubruk [2] had chosen in 1253 for his mission to the East. Before the Polos set off for Asia to the Mongols, the monks André de Longjumeau and John de Plano Carpini, commissioned by Pope Innocent IV, and later also William of Rubruk, commissioned by King Louis IX, had already begun such a journey in an official mission. After their return, they each wrote their own travel reports. After their stopover, the Polos arrived in the area then ruled by the Golden Horde and stayed for about a year near the Genghis Khan grandson Berke Khan on the Volga. Afterwards, the chaos of war that still prevailed there caused them to move further and further east across the Ural River and along the Silk Road (northern branch to southern Russia) to Bukhara.

Since they were prevented from returning by the consequences of the war, they stayed there for three years and finally joined a Persian legation on its way to the Great Kubilai Khan.[3] In the winter months of 1266, after a year’s journey, they arrived at the court of the Mongol ruler in Beijing (then name: Khanbaliq), where they were welcomed by the Khan. On their departure, the Khan gave the Polos a so-called païza in the form of a gold plaque, which guaranteed safe conduct and free supply in the territory of the Grand Khan. They were also commissioned by the Grand Khan to deliver a message to the Pope, asking him to send consecrated oil from the tomb of Jesus in Jerusalem and about one hundred Christian scholars to spread the Gospel among his subjects. Thus the Polos began their return journey to Venice, where they arrived around 1269. In the meantime, several successors had replaced the deceased pope, and an election for a successor had just begun. Marco Polo’s mother had also died.

Marco Polo’s Travel

Even before a new Pope could be elected, Niccolò and Maffeo Polo set off again in 1271, taking seventeen-year-old Marco with them. It was in Acre that he first set foot on Asian soil. Here the three Polos explained the purpose of their journey to the papal legate and asked him first to be allowed to continue on to Jerusalem, since the Mongolian ruler had asked Niccolò and Maffeo Polo on their first trip to Asia to bring him oil from the lamp of the Holy Sepulchre. With the requested permission, the Polos traveled to Jerusalem, where they were able to obtain the requested oil without any problems, and then returned to Acre. Gregory X, who was in Palestine at the time of his election as a crusader, now officially commissioned the Polos there as head of the church to continue their journey to the Grand Khan in order to convert him to Christianity and win him as an ally against Islam.

From the Holy Land to China

Afterwards, the journey continued via the city of Tabriz, which impressed the young Polo with its colorful bazaars, to Saveh. After Marco Polo the holy three kings were buried here. From there, their journey led them to the oasis city of Yasd, which was fed with water brought from the mountains by Qanates. The journey then led the Polos to Kerman, where the jewelers probably traded their horses for more robust camels. The next stops were Rajen, a city of smiths and a place of production of artistic steel products, and Qamadin, the final stop on a route that brought pepper and other spices from India. From Hormus, the trade travelers actually wanted to set out for China by sea, but the poor condition of the ships in Hormus made them abandon their plans. Through the considerable detours that were now necessary, Marco Polo reached the ruins of the city of Balch in 1273. The further journey led via the villages of Ishkaschim, Qala Panja, and in 1274 via the city of Kashgar on the western edge of the Taklamakan sand desert, further along the southern route of the Silk Road, which branched out there, to the oasis city of Nanhu. The city of Shazhou, today Dunhuang, was an important junction of the trade routes of that time, as the southern and northern routes to bypass the Taklamakan desert also met there again.

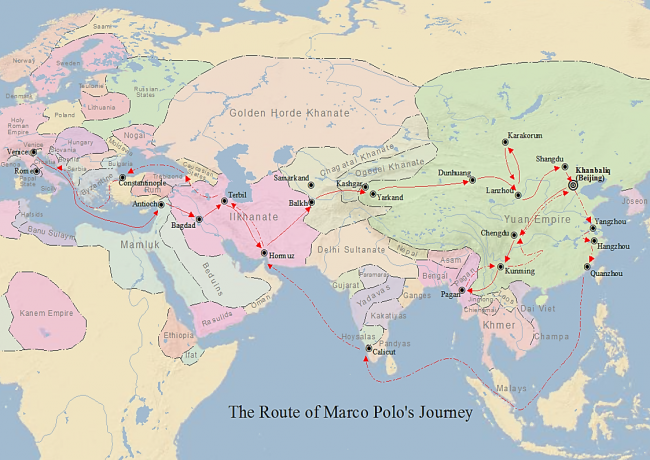

Map of Marco Polo’s travels

The Court of Kublai Khan

According to his report, Marco Polo, who had now finally reached Chinese territory, saw in this important oasis city for the first time a large number of Chinese who had settled in what was then one of the largest Buddhist centers in China. The group then traveled through the cities of Anxi, Yumen and Zhangye, arriving in Shangdu in 1275 as their actual destination. There Marco Polo met Kublai Khan,[3] the Grand Khan of the Mongols and grandson of Genghis Khan, at his summer residence. At that time, Kublai’s empire stretched from China to the area of today’s Iraq and in the north to Russia. The three merchant travellers settled here under the care of the ruler until 1291. The Grand Khan took a liking to the young European and appointed him his prefect. As such, Marco Polo roamed China in all directions for several years.

Marco Polo in China (Abbildung in dem Buch Il milione, 1298-1299)

A Cunning Plan

When restless times threatened to break out, the Polos wanted to travel back to Venice. Despite their petitions, the Grand Khan did not let them leave, since they had become a valuable support for him in the meantime. At that time, three Persian diplomats and their entourage appeared at the court of Kubilai Khan and asked for a bride for Khan Arghun of the Persian Il-Khanate. The Mongol ruler appointed the seventeen-year-old princess cooks for the marriage, which was to be taken to Persia. Since the overland route was too dangerous, the merchants seized this opportunity and suggested to the Grand Khan that the princess be escorted safely to Persia by sea together with the diplomats. Reluctantly, the Grand Khan finally accepted the only promising offer and finally allowed them to return home.

And Back Again

The return journey to Venice by sea began in 1291 in the port of Quanzhou, a cosmopolitan city with branches of all major religions. It was carried out on 14 junks with a total of 600 passengers, of whom only 17 survived in the end. On the stopovers in Sumatra and Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) Marco Polo got to know the local cultures and later described them in his travelogue. After 18 months of continued travel, the ship reached the Persian port of Hormus. Later, on the Black Sea in the empire of Trapezunt, today’s Trabzon, the officials there confiscated about 500 kilograms of raw silk from the sailors who wanted to bring the Polos home. In 1295, the travelers finally reached the Republic of Venice and are said to have been unrecognized by their relatives at first. Allegedly they identified themselves by cutting the hems of their clothes and taking out the gems they had brought with them.

Il Milione

According to the chronicler and biographer Giovanni Battista Ramusio, who had made him a “hero of the Serenissima”, Marco Polo took part some time later as a fleet commander in a naval war in which Venice had been involved for years with its archrival Genoa. In the naval battle of Curzola in 1298, he led a Venetian galley and fell into Genoese captivity, where he was held until May 1299. In the Palazzo San Giorgio, which was used as a prison, he was allegedly urged by his fellow prisoner Rustichello da Pisa, also known as the author of novels of chivalry, to dictate to him the report of his trip to the Far East. The result went down in literary history as Le divisament dou monde (“The Division of the World“), in French under the title Le Livre des merveilles du monde (“The Book of the Wonders of the World“).

Michael Henss, The Travels of Marco Polo in China and Central Asia [6]

References and further Reading:

- [1] Marco Polo at New Work Encyclopaedia

- [2] William of Rubruck and his Adventurous Journey to Karakorum, SciHi Blog

- [3] In Xanadu did Kublai Khan a Stately Pleasure-Dome Decree, SciHi Blog

- [4] Works by or about Marco Polo at Internet Archive

- [5] Marco Polo at Wikidata

- [6] Michael Henss, The Travels of Marco Polo in China and Central Asia, Asia Society @ youtube

- [7] W. Marsden (2004), Thomas Wright (ed.), The Travels of Marco Polo, The Venetian (1298)

- [8] Hans Ulrich Vogel (2012). Marco Polo Was in China: New Evidence from Currencies, Salts and Revenues. Brill.

- [9] Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [10] Moule, Arthur Christopher; Pelliot, Paul (1938). Marco Polo: The Description of the World. Vol. 1. London: George Routledge & Sons Limited.

- [11] Timeline of medieval explorers, via Wikidata