Natural and political observations mentioned in a following index, and made upon the bills of mortality. By Capt. John Graunt

On April 18, 1674, English herberdasher and statistician John Graunt passed away. Graunt is considered by many historians to have founded the science of demography as the statistical study of human populations. For his published analysis of the parish records of christenings and deaths, he was made a charter member of the Royal Society.

“Having always observed that most of them who constantly took in the weekly Bills of Mortality made little other use of them than to look at the foot how the burials increased or decreased, and among the Casualties what had happened, rare and extraordinary, in the week current; so as they might take the same as a Text to talk upon in the next company, and withal in the Plague-time, how the Sickness increased or decreased, that the Rich might judge of the necessity of their removal, and Trades-men might conjecture what doings they were likely to have in their respective dealings.”— John Graunt, from Natural and Political Observations Mentioned in a Following Index and Made upon Bills of Mortality (1662)

John Graunt – Early Years

John Graunt was born on April 24, 1620, in London, the eldest of seven or eight children of Henry Graunt, a draper (a dealer in clothing and dry goods) who had moved to London from Hampshire, and his wife Mary. He worked in his father’s shop until his father died in 1662, and became a prosperous haberdasher until his business was destroyed in the London fire of 1666 in the City. In 1650, he was able to secure the post of professor of music for his friend William Petty, a physician, later invented the horse-propelled military tank and was appointed surveyor general of Ireland. He served in various ward offices in Cornhill ward, becoming a common councilman about 1669–71, warden of the Drapers’ Company in 1671 and a major in the trained band.

Studying Death Records

While still active as a merchant, he began to study the death records that had been kept by the London parishes since 1592 over a 70 year period. Noticing that certain phenomena of death statistics appeared regularly, he was inspired to write “Natural and Political Observations mentioned in a following index, and made upon the Bills of Mortality With reference to the Government, Religion, Trade, Growth, Ayre, diseases, and the several Changes of the said City.” (1662). He produced four editions of this work; the third (1665) was published by the Royal Society, of which Graunt was a charter member. In his book Graunt explained that the death accounts were kept as the number of deaths rose from the plague, a catastrophic illness whose germs were carried by fleas that lived as parasites on rats. In the year 1625 alone, one-fourth of England’s population died, many from the plague.[1] Together with William Petty, Graunt developed early human statistical and census methods that later provided a framework for modern demography. He is credited with producing the first life table, giving probabilities of survival to each age. Graunt is also considered as one of the first experts in epidemiology, since his famous book was concerned mostly with public health statistics.

First Population Statistics of London

For his book, Graunt had used analysis of the mortality rolls in early modern London as Charles II and other officials attempted to create a system to warn of the onset and spread of bubonic plague in the city. Though the system was never truly created, Graunt’s work in studying the rolls resulted in the first statistically based estimation of the population of London. The erudition of the Observations led Graunt to the Royal Society, where he presented his work and was subsequently elected a fellow in 1662 with the endorsement of the King. He was chosen as a member of the council in November 1664 and represented the society at various meetings.

Death Rates and Consequences

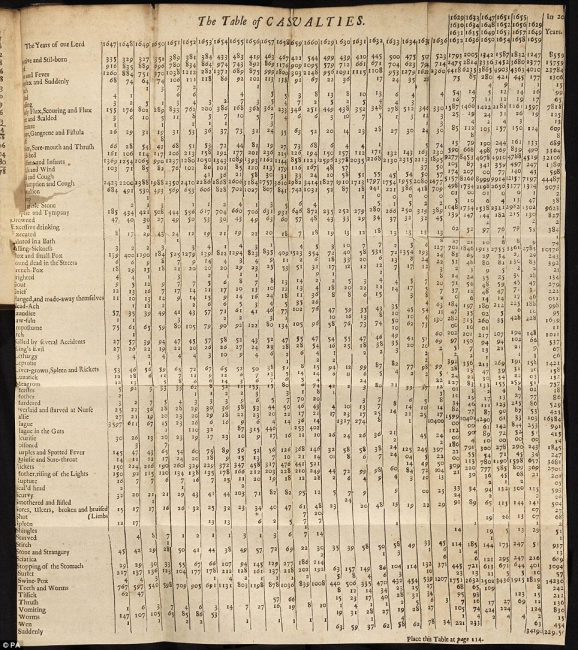

Graunt classified death rates according to the causes of death, among which he included overpopulation: he observed that the urban death rate exceeded the rural. He also found that although the male birth rate was higher than the female, it was offset by a greater mortality rate for males, so that the population was divided almost evenly between the sexes. Perhaps his most important innovation was the life table, which presented mortality in terms of survivorship. Using only two rates of survivorship (to ages 6 and 76), derived from actual observations, he predicted the percentage of persons that will live to each successive age and their life expectancy year by year.[2] Graunt’s book on the Bills of Mortality had great influence throughout Europe. It has been noted that soon after its publication, France embarked on the most precise registering of births and deaths in all of Europe.[1]

Table of Casualties in Natural and Political Observations Made Upon the Bills of Mortality (5th edition, published 1676)

Samuel Pepys and John Graunt

Famous diarist Samuel Pepys mentions Graunt several times in his diaries. He appears to have had a business relationship with him from 1661 to 1663.[5] In the diaries Pepys refers to him as Mr. Graunt with one exception. An entry in 1668 reads Captain Graunt. It seems likely that at this time he was an officer of one of the Trained-Bands. Graunt was made a governor of the New River Company in 1666. This company supplied water to the city of London from an Islington water house.[3]

The Great Fire of London

On September 2, 1666, Graunt’s house was destroyed in the Great Fire of London [4] and he encountered other financial problems leading eventually to bankruptcy. His daughter became a nun in a Belgian convent and Graunt decided to convert to Catholicism at a time when Catholics and Protestants were struggling for control of England and Europe, leading to prosecutions for recusancy. Graunt had been brought up as a Puritan but had lived as an anti-Trinitarian for a number of years before his final conversion to Catholicism. Anti-Trinitarians rejected the notion that God is made up of three distinct beings, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.[1] As a result, he was also accused of being involved in the Great Fire of London. As a consequence of the charge, he lost his position with a water company. He died of jaundice and liver disease at the age of 53.

Philippe Rigollet, 1. Introduction to Statistics, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “John Graunt.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004.

- [2] John Graunt, English statistician, at Britannica Online

- [3] John Graunt, at cerebro

- [4] The Great Fire at London, SciHi blog, September 2, 2013.

- [5] The Amazing Diary of Samuel Pepys, Esq., SciHi Blog

- [6] John Graunt at Wikidata

- [7] Works by or about John Graunt at Wikisource

- [8] Stephan, Ed. “John Graunt (1620-1674)

- [9] John Graunt, Natural and Political Observations mentioned in a following Index, and made upon the Bills of Mortality, 1665

- [10] Lewin, C. G. (2004). “Graunt, John”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11306

- [11] Philippe Rigollet, 1. Introduction to Statistics, MIT 18.650 Statistics for Applications, Fall 2016, MIT Open CourseWare @ youtube

- [12] Graunt, John; Petty, William; Morris, Corbyn; J.P. (1759). Collection of Yearly Bills of Mortality, from 1657 to 1758 Inclusive.

- [13] Timeline of Demographers, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #37 | Whewell's Ghost