Johann Friedrich Struensee (1735 – 1772)

On August 5, 1735, German physician Johann Friedrich Struensee was born. He became royal physician to the mentally ill King Christian VII of Denmark and a minister in the Danish government, where he tried to carry out widespread reforms. His affair with Queen Caroline Matilda caused his downfall and dramatic death.

Johann Friedrich Struensee – Early Years

Johann Friedrich Struensee was born in Halle as the second of six children of the pietist pastor and professor of the University of Halle Adam Struensee. His mother Maria Dorothea was the only daughter of the Count’s personal physician at Berleburg Castle and later Danish Councillor of Justice Johann Samuel Carl. Carl had been the personal physician of the Danish King Christian VI from 1732 to 1742 and had participated in the reform of the Danish health system in 1740. In Halle young Struensee visited the Latina of the Francke Foundations and began his medical studies a few days before his fifteenth birthday. Even before his 20th birthday he completed his studies with a doctorate on 14 February 1757.

On July 12, 1757, Adam Struensee became the main pastor of the Trinity Church in Altona, then ruled by the Danish king. Johann Friedrich Struensee, who had just turned twenty, followed his parents and in early 1758 found employment as a city physician and doctor for the poor. As a doctor, Struensee successfully fought the spread of epidemics by improving hygiene – for example, a separate bed for each orphan – and introduced smallpox vaccination. Instead of the usual treatment by bloodletting and sweating, he recommended fresh air in the sickroom and the destruction of the deceased’s clothes and bedding. His experience with such hygiene measures and autopsies led him to conclude that diseases were caused by infection. The doctrine of juices, to which most of his colleagues adhered, he rejected as superstition. Because of his new-fangled methods and teachings, Struensee met with rejection from many colleagues.

Medical Research

Struensee reported on his research results in various medical papers. In 1764 he published the veterinary treatise Versuch von der Natur der Viehseuche und der Art sie zu heilen (Attempt of the nature of the cattle disease and the way to cure it), the first medical description of foot-and-mouth disease. In the monthly magazine Zum Nutzen und Vergnügen (For use and pleasure), which appeared in 1759, he was also active as a journalist. In 1763 this writing, which satirically criticized not only the doctors but also the nobility, was banned at the instigation of Hamburg’s principal pastor Goeze. Struensee, however, continued to publish in various periodicals. In his essays he exposed the connections between lack of education, lack of hygiene and diseases in the poor quarters and recommended reforms. In doing so, he saw the state as having a duty to ensure the health and education of its population, because “increasing the number of inhabitants is one of the noblest things that makes the statisticians move.

The King’s Personal Physician

Struensee was known to be a progressive man with ideals from the Age of Enlightenment, which was not welcomed in every part of society. Even though his financial situation did not let him expect a carefree living, his behavior soon caused him to socialize with the high society. He met the Danish minister of Foreign Affairs and soon began writing first essays on Enlightenment treatises, published in journals. Getting in contact more and more with Denmark’s Royalty, in 1767 he was recommended to take care of young King Christian VII during his tour across Europe during which he received the honorary degree of Doctor in Medicine from Cambridge. During the journey, Struensee had gained the trust of the king, who let himself be guided by him. The King therefore asked him to accompany him to Copenhagen. At the Danish court Struensee was awarded the title of Royal Reader by Christian VII, and in May 1769 he was appointed to the Real Budget Council. As early as 1769, the first laws were passed to improve the situation of unmarried mothers and a midwife order was introduced. But Struensee was soon drawn into court intrigues that forced him to obtain a secure position at court.

The King’s Personal Counselour

During a smallpox epidemic in Copenhagen in 1770, Struensee became a member of the commission for the introduction of smallpox vaccination and also vaccinated Crown Prince Friedrich against smallpox. He thus finally won the affection and trust of the royal couple and was promoted to Cabinet Secretary and Conference Councilor. After Struensee had won the king’s trust, he was able to easily push through his reforms thanks to Kongelov. In 1770, Christian VII signed the first Struensee laws: This prohibited the accumulation of titles and decorations without merit, and introduced freedom of speech and the press. Struensee accompanied the royal couple to Frederiksberg Castle, Traventhal Castle and Hirschholm Castle for summer stays. Isolated from the influences of the royal court and those of the royal counsellors, he discussed his reform ideas with the king there and issued a large part of his decrees. On 18 December 1770 he was officially appointed as a personal physician.

Reforming the State of Denmark

Within a short time Struensee tried to reform the entire Danish state in the spirit of the Enlightenment. In 16 months he drafted a total of 633 decrees, which meant a complete reorganisation. In socio-medical issues, Struensee implemented findings from his time as a doctor for the poor. But also government and administration should become more effective. Struensee, who himself had no experience in these areas, but could count on the support of his brother, reorganised the entire government along the lines of the Prussian General-Ober-Finanz-Kriegs- und Domainen-Direktorium, which meant a radical break with Danish tradition. The first successes were quickly achieved: The relocation of the cemeteries outside the city, the paving of streets and street lamps made Copenhagen cleaner and safer. Within a year, the radical austerity measures brought the state a nearly balanced budget.

The Queen’s Lover

The king himself encouraged Struensee’s acquaintance with his wife Caroline Mathilde, whose depressions he was to treat. Struensee advised the royal couple to break out of the strict court etiquette and ride out together. He also advised Caroline Mathilde to educate the crown prince according to the principles of Rousseau‘s Emile.[8] Frederick was given a middle-class playmate and grew up with far less luxury than was considered appropriate for royal offspring, but with far more freedom. Although the 19-year-old queen was initially suspicious of her husband’s new favourite, she soon took a great liking to the rides suggested by Struensee and then to the man himself. Their relationship deepened quickly. It is said that there was even a secret passage between Struensee’s apartment and the Queen’s chambers. During the summer stays, Struensee spent a lot of time alone with the Queen.

While at first, Struensee’s political influence operated very controlled, keeping a low profile, he later on appointed himself to several offices and enforced several treatises. It was his duty to present reports from all governmental departments to the king. King Christian was, according to Struensee, in a pretty bad shape during this period, wherefore Struensee began dictating whatever he favored. He began dismissing several people from their offices while establishing the cabinet as the surpreme power. In the 18 months of his power, Struensee passed over 1000 orders including the abolition of noble privileges, introduction of various taxes, the abolition of torture and many more.

Soon their love affair became public knowledge. But the king didn’t care about the rumors. On the occasion of his birthday on January 29, 1771, he bestowed the Order of Matilda on Struensee, which had been donated by the queen. It was widely accepted that Louise Auguste was Struensee’s daughter. While intercessions for the pregnant queen and later thanksgiving prayers for the birth of the princess were made in the churches on Struensee’s orders, many people left the churches in silence. That Struensee had declared adultery a private matter by decree was considered an open admission of guilt.

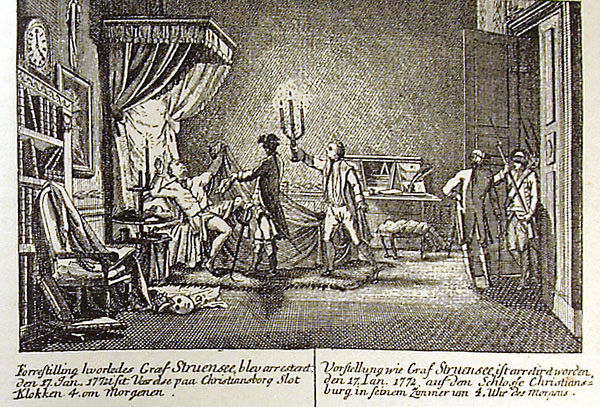

The Arrest of Struensee, Fabiricius: Illustrated History of Denmark for the People, 1915 18th century woodcut

Arrested and Sentenced to Death

Firstly, the Danish people liked his reforms and saw new possibilities. After a while, he received lots of distrust, operating every business in German and firing numerous governmental officials without pensions. Struensee’s enemies increased. During the summer of 1771, the king and queen as well as Struensee and some members of the Royal Court stayed at Hirschholm Palace, where the queen gave birth to her daughter. The ill will against Struensee grew and on January 17, 1772 he was arrested along with the queen. He was charged with usurpation of royal authority and faced death penalty in spring of the same year.

Despite his doubtful behavior, Struensee was highly influenced by the Age of Englightenment and his actions are assumed to have altered the decisions of leading revolutionaries and governmental officals after his death. Neither the king’s decision to support Struensee and his reforms nor his state of mind were taken into account in the judgement. He himself was not questioned during the entire trial. He was only presented with the completed sentence for signature, just as he had been presented with the arrest warrant before. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing,[9] who already knew Struensee from his time in Altona and who was in Copenhagen at the same time, had already written to his future wife Eva König on 31 January: “As you can see, you have forced your case from the king”. A sketch, allegedly made later by Christian VII, bears the inscription:

“The Count Struensee, a very great man, died in 1772 at the command of Queen Juliane Marie, and Prince Frederick’s and not mine. And by the will of the Council of State. I would like to have saved them both.“

John Merryman, The Enlightenment and the Public Space, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Struensee Affair at nndb

- [2] Struensee at Princeton

- [3] The Doctor who ran Denmark

- [4] Jutta Nehring: Dänemarks kurzer Sommer der Aufklärung. In: Preußische Allgemeine Zeitung, 3. August 2012

- [5] . New International Encyclopedia. 1905

- [6] . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- [7] Dewey, Donald. “The Danish Rasputin” Scandinavian Review (2013) 100#1

- [8] “Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains” – Jean-Jacques Rousseau, SciHi Blog

- [9] The Idea of Tolerance in the Theatre and Essays of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, SciHi Blog

- [10] John Merryman, The Enlightenment and the Public Space, European Civilization, 1648-1945 (HIST 202) at youtube

- [11] Johann Friedrich Struensee at Wikidata

- [12] Timeline of Court Physicians, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #05 | Whewell's Ghost