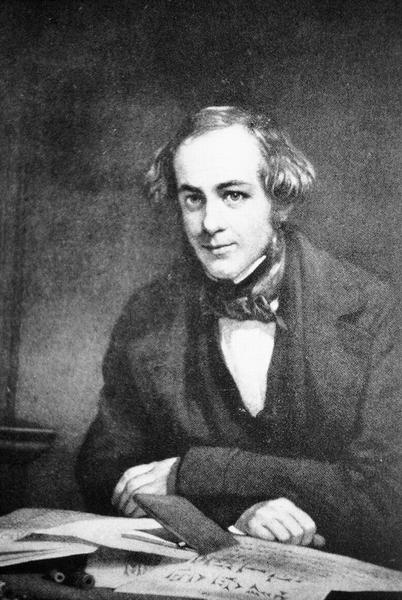

Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet (1810-1895)

On April 11, 1810, British East India Company army officer, politician and Orientalist Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson was born. As an army officer, became interested in antiquities after his assignment to reorganize the Persian army. He accomplished the translation of the Old Persian portion of the trilingual mutilingual cuneiform inscription of Darius I on the hillside at Behistun, Iran, which provided the key to the deciphering of Mesopotamian cuneiform script.

Henry Rawlinson – Early Years

Rawlinson was born in Chadlington, Oxfordshire, England, the second son of Abram Tyack Rawlinson, and elder brother of the historian George Rawlinson. In 1827 he started his military career, going to India as a cadet under the British East India Company. After six years with his regiment as subaltern, during which time he had become proficient in the Persian language, he was sent to Persia in company with other British officers to drill and reorganize the Shah’s troops. There he became keenly interested in Persian antiquities and inscriptions, and deciphering of the famous and hitherto undeciphered cuneiform character inscriptions at Behistun (بیستون) became his goal.

The Behistun Inscriptions

The Behistun inscriptions are located near the city of Kermanshah in western Iran. In 1598, the Englishman Robert Sherley saw the inscription during a diplomatic mission to Persia and brought it to the attention of Western European scholars. The members of his expedition incorrectly came to the conclusion that it was Christian in origin. Italian explorer Pietro della Valle visited the inscription in the course of a pilgrimage in around 1621. German surveyor Carsten Niebuhr visited the inscriptions in around 1764, publishing a copy of the inscription in the account of his journeys in 1778. Niebuhr’s transcriptions were used by Georg Friedrich Grotefend and others in their efforts to decipher the Old Persian cuneiform script. [4]

Old Persian Inscriptions

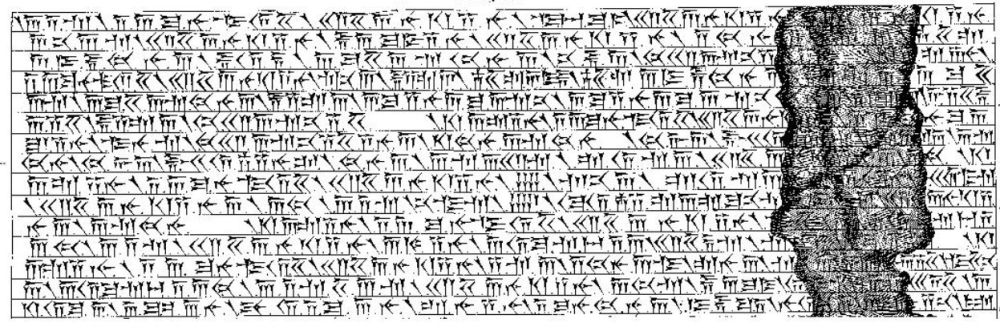

In late May 1836, Rawlinson climbed repeatedly up to the ledge to copy the first lines of the Old Persian inscriptions [3]. He began to transcribe the Old Persian portion of the trilingual inscriptions in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian written by the Medes and Persian ruler Darius the Great sometime between his coronation as king of the Persian Empire in the summer of 522 BC and his death in autumn of 486 BC. After two years of work, Rawlinson published his translations of the first two paragraphs of the inscription in 1837. However, the friction between the Persian court and the British government ended in the departure of the British officers and Rawlinson had to interrupt his efforts.

Afghan War and Baghdad

In 1840, Rawlinson was appointed political agent at Kandahar and due to his political labors being as meritorious as was his gallantry during various engagements in the course of the Afghan War, he was rewarded by the distinction of Companion of the Bath (C.B.) in 1844. A fortunate chance, by which he became personally known to the governor-general, led to his being appointed as political agent in Ottoman Arabia. Through this, he was able to settle in Baghdad, where he devoted much time to his cuneiform studies. With considerable difficulty and at no small personal risk, he made a complete transcript of the Behistun inscription, which he was also successful in deciphering and interpreting.

The Behistun Inscriptions, Column 1 (DB I 1-15), sketch by Friedrich von Spiegel (1881)

Decipherment of Cuneiform

For centuries, travelers to Persia had noticed carved cuneiform inscriptions and were intrigued. Attempts at deciphering these Old Persian writings date back to medieval times though being largely unsuccessful. In 1625, Roman traveler Pietro Della Valle, brought back a tablet written with cuneiform glyphs he had found in Ur together with the copy of five characters he had found in Persepolis. Della Valle already understood that the writing had to be read from left to right, but did not attempt to decipher the scripts. In the 18th century, Carsten Niebuhr brought the first reasonably complete and accurate copies of the inscriptions at Persepolis to Europe. Bishop Friedrich Münter of Copenhagen discovered that the words in the Persian inscriptions were divided from one another by an oblique wedge and that the monuments with the inscriptions must belong to the age of Persian emperor Cyrus and his successors. One word, which occurs without any variation towards the beginning of each inscription, he correctly inferred to signify “king“. By 1802 Georg Friedrich Grotefend had determined that two king’s names mentioned were Darius and Xerxes, and had been able to assign correct alphabetic values to the cuneiform characters which composed the two names.[5]

A Rosetta Stone for Cuneiform

When Henry Rawlinson copied the Behistun Inscriptions in Persia in 1835, he realized that they consisted of identical texts in the three official languages of the empire: Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite. Thus, the Behistun inscription was to the decipherment of cuneiform what the Rosetta Stone was to the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Rawlinson correctly deduced that the Old Persian was a phonetic script and he successfully deciphered it. In 1837 he finished his copy of the Behistun inscription, and sent a translation of its opening paragraphs to the Royal Asiatic Society. Before his article could be published, however, the works of Norwegian-German orientalist Christian Lassen and the French orientalist Eugène Burnouf reached him, necessitating a revision of his article and the postponement of its publication. The original inscriptions published by Niebuhr contained a list of the satrapies of Darius. Based on that, Burnouf and Laasen independently had been able to identify an alphabet of thirty letters, most of which they had correctly deciphered. Due to further causes of delay, the first part of the Henry Rawlinson’s Memoir was published in 1847; the second part did not appear until 1849. By then, the task of deciphering the Persian cuneiform texts was virtually accomplished.

Later Years

Henry Rawlinson collected a great amount of invaluable information in addition to much geographical knowledge gained in the furtherance of various explorations. In 1849, he returned to England and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He donated his valuable collection of Babylonian, Sabaean, and Sassanian antiquities to the trustees of the British Museum, who in return gave him a considerable grant to enable him to carry on Assyrian and Babylonian excavations. In 1851, he became consul general at Baghdad and succeeded the archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in the work of obtaining ancient sculptures for the museum. On resigning his post with the British East India Company in 1855, Rawlinson was knighted and made a crown director of the company. The remaining 40 years of his life were full of activity – political, diplomatic, and scientific – and were mainly spent in London. Henry Rawlinson became a trustee of the British Museum, serving from 1876 till his death in 1895.

Irving Finkel, Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson at Britannica Online

- [2] The Real Sir Henry Rawlinson

- [3] RAWLINSON, HENRY – Contributions to Assyriology and Iranian Studies, at Encyclopedia Iranica

- [4] Carsten Niebuhr and the Decipherment of Cuneiform, SciHi Blog

- [5] At the Beginning was a Bet – Georg Friedrich Grotefend and the Cuneiform, SciHi Blog

- [6] George Smith and the Epic of Gilgamesh, SciHi Blog

- [7] Robert Koldewey and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, SciHI Blog

- [8] Sir Henry Rawlinson at Wikidata

- [9] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Rawlinson, Sir Henry Creswicke“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 928–929.

- [10] Rawlinson, George (1898). A Memoir of Major-General Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson. London: Longmans, Green and Co

- [11] Irving Finkel, Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing, The Royal Institution @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of English Assyriologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vo. #36 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: The man who cracked the cuneiform code | John Manders' Blog