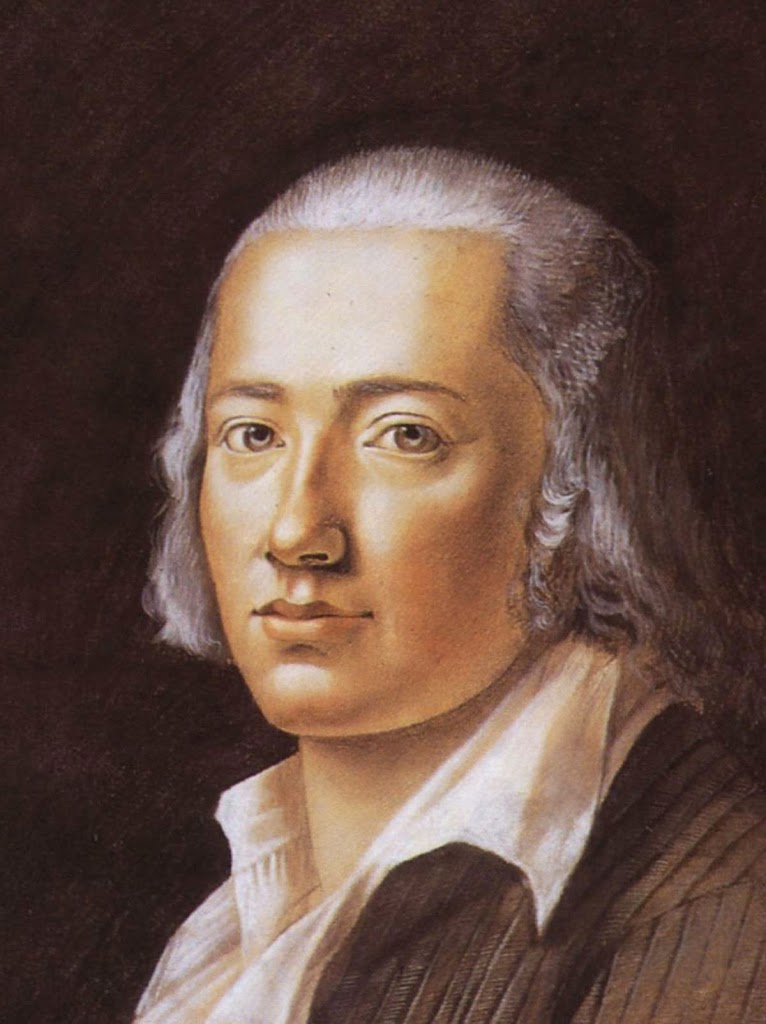

Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843)

On March 20, 1770, major German lyric poet of Romanticism, Friedrich Hölderlin was born. Hölderlin was also an important thinker in the development of German Idealism, particularly his early association with and philosophical influence on his seminary roommates Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel [3] and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling. The poetry of Hölderlin, widely recognized today as one of the highest points of German literature, was little known or understood during his lifetime and was largely ignored for the rest of the 19th century.

“Being at one is god-like and good, but human, too human, the mania

Which insists there is only the One, one country, one truth, and one way.”

– Friedrich Hölderlin, The Root of All Evil

Youth and Education

Friedrich Hölderlin was born in Lauffen am Neckar in the Duchy of Württemberg, where he was brought up by his mother, because his father, the manager of a church estate, already died when the boy was only two years old. In 1774, Hölderlin’s mother Johanna Christina Hölderlin, then aged 26, married the counselor Gock, mayor of Nürtingen, who died when he was nine. Friedrich Hölderlin was raised by his twice-widowed mother in a religious environment. After visiting school in Denkendorf and Maulbronn, Hölderlin studied theology at the Tübinger Stift, where his fellow-students included Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, who would become important figures of German idealism philosophy.

Meeting Fichte, Schiller, and Goethe

Hölderlin came to Jena in 1794, after Johann Gottlieb Fichte [4] had taken over the chair of philosophy there and whose classes Hölderlin attended eagerly. During that period, Hölderlin was a staunch supporter of the French Revolution, which was seen by many German intellectuals as a source of hope for the future. Hölderlin found a position as a private tutor. At the same time Hölderlin also met Friedrich Schiller [5] and Johann Wolfgang Goethe[6] and began writing his epistolary novel Hyperion, which should become his masterpiece. Hölderlin’s ethical views emphasize an understanding of life as torn between two principles: a hankering after this original unity and freedom’s desire to constantly assert itself. His novel Hyperion illustrates this struggle and how the integration of these two principles is set as a goal for life.

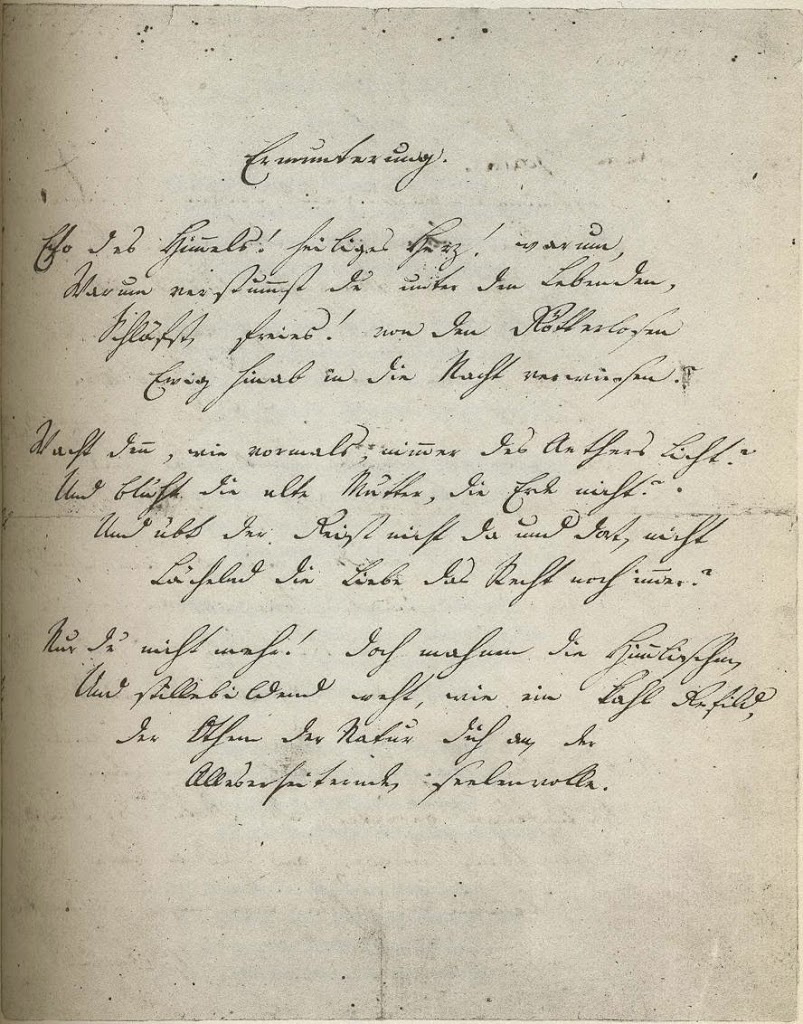

Hölderlin’s autograph of the first 3 stanzas of

his ode “Ermunterung” (“Exhortation”)

Emotional Upheaval

As a tutor in Frankfurt from 1796 to 1798 he fell in love with Susette Gontard, the wife of his employer. The feeling was mutual, and this relationship was the most important in Hölderlin’s life, who addressed Susette in his poetry under the name of ‘Diotima‘. Their affair was discovered and Hölderlin was harshly dismissed. The emotional upheaval caused by the end of the impossible liaison with Susette had a detrimental effect on his health. In 1800, after his disillusionment with philosophy that led him to abandon any plans to find an academic position, he spent a year recovering in Switzerland and decided to devote the rest of his life to writing poetry. In 1802, the news of Susette’s death, however, drove him to near insanity. Meanwhile, Hölderlin had found a sinecure as court librarian in his hometown Nürtingen. Treatment enabled him to continue writing at intervals while working as a librarian in Homburg until 1807 when he became insane (though harmless).

A View Across the Neckar

The following year Hölderlin was discharged as incurable and given three years to live, but was taken in by the carpenter Ernst Zimmer (a cultured man, who had read Hyperion) and given a room in his house in Tübingen, which had been a tower in the old city wall, with a view across the Neckar river and meadows. Zimmer and his family cared for Hölderlin until his death in 1843. Hölderlin continued to write poetry of a simplicity and formality quite unlike what he had been writing up to 1805. As time went on he became a kind of minor tourist attraction and was visited by curious travelers and autograph-hunters. Often he would play the piano or spontaneously write short verses for such visitors, confining himself to conventional subjects such as Greece, the Seasons, or The Spirit of the Times, pure in versification but almost empty of affect, although a few of these have a piercing beauty and have been set to music by many composers.

“What is all that men have done and thought over thousands of years, compared with one moment of love. But in all Nature, too, it is what is nearest to perfection, what is most divinely beautiful! There all stairs lead from the threshold of life. From there we come, to there we go.” (Friedrich Hölderlin, from ‘Hyperion’)

Richard Capobianco: “Heidegger on Hölderlin on ‘Nature’s Gleaming'”, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Friedrich Hölderlin biography at Britannica Online

- [2] Hölderlin in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [3] Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel and the Secret of Philosophy, SciHi Blog

- [4] Johann Gottlieb Fichte and the German Idealism, SciHi Blog

- [5] Friedrich Schiller ‘The Robbers’, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Life and Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, SciHi Blog

- [7] Homepage of Hölderlin-Archiv

- [8] Works by or about Friedrich Hölderlin at Internet Archive

- [9] Friedrich Holderlin (1909). Gedichte (in German). Jena: Eugen Diederichs.

- [10] Friedrich Hölderlin at Wikidata

- [11] Richard Capobianco: “Heidegger on Hölderlin on ‘Nature’s Gleaming'”, 2010, Stonehill College @ youtube

- [12] Martin Glaubrecht: Hölderlin, Friedrich. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7, S. 322–332

- [13] Adolf Wohlwill: Hölderlin, Johann Christian Friedrich. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 12, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1880, S. 728–734.

- [14] Timeline for Friedrich Hölderlin, via Wikidata