Matterhorn, Image: Juan Rubiano

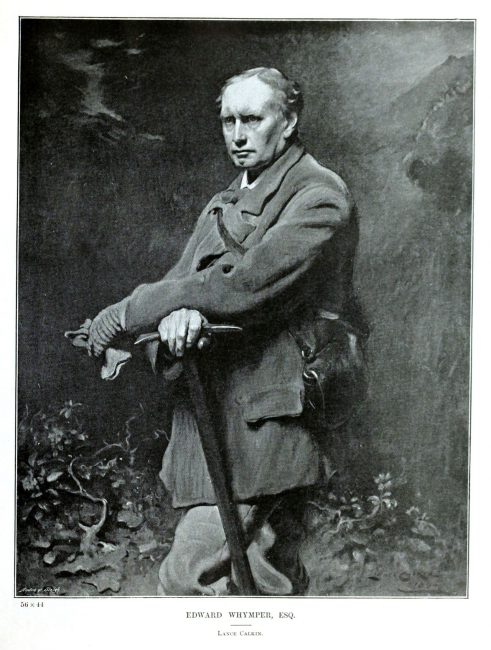

On April 27, 1840, English mountaineer, explorer, illustrator, and author Edward Whymper was born. He is best known for the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865; four members of his party were killed during the descent.

From Wood Engraving to the Western Alpes

Edward Whymper was born in London, England as the second of eleven children. He learned and practiced wood-engraving starting at very young age. In order to draw scenery pictures for a London publisher in the central and western Alps, Whymper began exploring the scenery quite often. His works included an unsuccessful an illustration of an attempt to ascend Mont Pelvoux. Only one year later, Whymper eventually managed the mountain as one of the first of numerous expeditions which threw much light on the topography of an area at that time very imperfectly mapped. While standing on top of Mont Pelvoux, Whymper noticed that it was overtopped by a neighbouring peak, the Barre des Écrins, which was climbed by Whymper along with Horace Walker, A. W. Moore and guides Christian Almer senior and junior in 1864. In the following years, Whymper successfully finished expeditions in the Mont Blanc massif and the Pennine Alps.

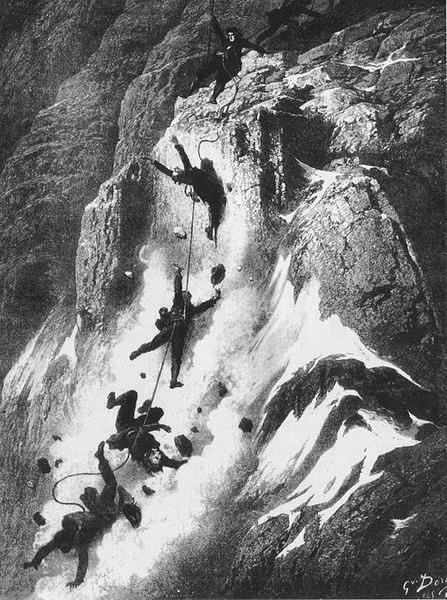

Matterhorn desaster, drawn by Gustave Doré

Matterhorn – The Last unconquered Alpine Summit

When Whymper decided to climb the Matterhorn, he already had a huge rival. Jean-Antoine Carrel, an Italian guide previously attempted to reach its summit but failed several times. He is supposed to have said that a native Italian should be the first to achieve this goal and not an English man like Whymper. By 1863, the Matterhorn remained as the last unconquered great alpine summit and an Alpine Society was planned in order to support the local climbers. However, Whymper’s party of eight team members started from Zermatt towards the ridge where they reached the base of the peak and continued up to 3380 meters where they managed to set the bivouac. After a longer rest, the group continued without ropes and reached the foot of the much steeper upper peak that lies above the shoulder. When the summit was close, Whymper and Michel Croz detached themselves and “ran a neck-and-neck race, which ended in a dead heat. At 1.40 p.m. the world was at our feet, and the Matterhorn was conquered. Hurrah! Not a footstep could be seen“. Standing at the top, Whymper saw his rival Carrel and his team about 200 metres below, still dealing with the most difficult parts of the ridge. Whymper and Croz yelled and poured stones down the cliffs to attract their attention. When seeing his rival on the summit, Carrel and party gave up on their attempt and went back to Breuil.

The Catastrophe

However, a difficult part was still in front of Whymper and his team: the descent. Even though the men climbed down with great care, only one man moving at a time, one of them slipped and fell on Croz, who was in front of him. Croz, who was unprepared, was unable to withstand the shock. Both fell and pulled down the others. On hearing Croz‘ shout Whymper and his team member Taugwalder stood very firm but the rope broke. Whymper could only watch them slide down the slope, falling from rock to rock and finally disappearing over the edge of the precipice. After the catastrophe, the remaining men were able to secure themselves and continue the descent until reaching a safer place. They searched for traces that might lead to their companions, but stayed unsuccessful. On 15 July, 1865 they reached Zermatt. One day later, a rescue team left in order to recover the men’s bodies, but only three were found.

Edward Whymper (1840-1911)

Did he Cut the Rope?

After the accident, Edward Whymper had to answer numerous questions and was accused of having betrayed his companions and the guide Peter Taugwalder was accused, tried, and acquitted. Many accused him to have cut the rope between him and Lord Francis Douglas to save his life. As the catastrophe was very present in the world’s media, Queen Victoria even considered banning climbing to all British citizens but decided, after consultation, not to forbid mountaineering.

The search for truth / First ascent of the Matterhorn – 150 years later, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Edward Whymper at Britannica Online

- [2] Blueplaque commemorates Matterhorn climber Edward Whymper

- [3] Cliffhanger at the Top of the World

- [4] “Because it’s there” – George Mallory and Mount Everest, SciHi Blog

- [5] More SciHi Blog articles on Mountaineering

- [6] Edward Whymper at Wikidata

- [7] The Matterhorn at Wikidata

- [8] The search for truth / First ascent of the Matterhorn – 150 years later, Matthias Taugwalder @ youtube

- [9] Map of European Mountains above 1,000 meters elevation above sealevel, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #02 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol: #38 | Whewell's Ghost