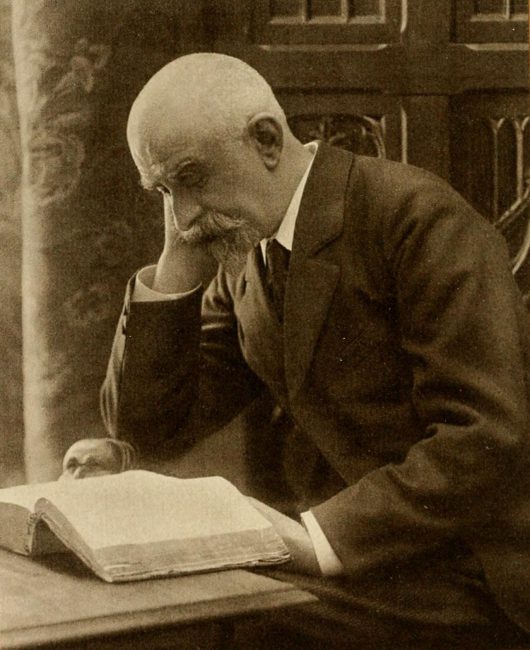

Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907)

On May 12, 1907, French writer and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans passed away. Hysmans is most famous for the novel “À rebours”, by which he broke from Naturalism and became the ultimate example of “decadent” literature. Huysmans’ work is considered remarkable for its idiosyncratic use of the French language, large vocabulary, descriptions, satirical wit and far-ranging erudition.

“Immersed in solitude, he would dream or read far into the night. By protracted contemplation of the same thoughts, his mind grew sharp, his vague, undeveloped ideas took on form.”

― Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature

Youth and Education

Joris-Karl Huysmans was born as Charles Marie Georges Huysmans on February 5, 1848, in Paris, France, the son of the Dutch lithographer Godfried Huysmans and the teacher Malvina Badin. After his father’s death, his widow and bookbinder Jules Og married in 1857 and Huysmans was sent to boarding school for resentment against his stepfather, where he spent a less than happy time at school. After graduating from high school, he took up a position as a middle clerk in the French Ministry of the Interior. There he stayed – interrupted by several leave of absence – until 1898.

First Publications as an Author

Besides his profession Huysmans worked as an author. Initially, he published shorter texts in journals. His first publication in 1874 was a collection of poems entitled Le Drageoir aux épices, using the Flemish first name Joris-Karl for the first time. In 1876 he met Émile Zola and joined the group of naturalists gathered around him.[1] In the same year he published his first novel Marthe, histoire d’une fille. The work was influenced by the naturalistic novel Germinie Lacerteux by the Goncourt brothers and Zolas Thérèse Raquin (1867). Huysmans, however, wrote so drastically that the book was banned for some time as immoral. In 1877 he testified to his friendship with Zola with a series of laudatory magazine articles about him and his new novel L’Assommoir.

The Parisian Lower Class Milieu

Huysman’s narrative works are also mainly set in the Parisian lower class milieu and are determined by a drastic realism. It’s the novel: Les sœurs Vatard (The Sisters V., 1879), which describes the mediocore, amorous and professional existence of two booksellers; the story Sac au dos (the bag on the back), which he wrote for the antimilitarist anthology Les soirées de Medan, published by Zola in 1880; the novel En ménage (Life in Twos, 1881), in which he presents the artist’s all too familiar problem between the urge for undisturbed creativity and the need for a sexual and affective relationship, but also confronts two types of artist in the form of a writer more close to reality and an aesthetic painter who is far removed from reality.

Au Rebours Became a Cult Book

In 1883 Huysmans published an anthology of art critiques from the years 1879-1882 under the title L’Art moderne (modern art). In 1884 he published the novel À rebours (Against the Grain), which was to secure his place in literary history. The minimal plot revolves around a decadent and neurotic young aristocrat named Jean Floressas Des Esseintes. The latter is increasingly withdrawing from the social reality which is unsatisfactory for him. He spins himself into an artificial world of aestheticism and mysticism in his suburban house and gradually ends up on the brink of mental derangement. The novel was actually intended as a naturalistic study of a “decadent” individual who is hereditary, ill and has many features of the author himself. However, many readers have taken it as a “breviary of decadence” in which they recognized their own problems and a problem of their time. For a while, A rebours became a cult book, not only for followers of naturalism, but also for those of the symbolist school. Foreign readers like Oscar Wilde were also impressed.[2] The great poet Mallarmé formulated symbolist poetics in 1885 in a long poem with the paradoxical title Prose pour Des Esseintes.

Academie Goncourt

“Already, he was dreaming of a refined solitude, a comfortable desert, a motionless ark in which to seek refuge from the unending deluge of human stupidity.”

― Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature

In 1890 Huysmans was one of the founders of the Académie Goncourt and became its first chairman. At the same time, apparently once again entering a phase of searching for meaning, he began to open himself to the influence of people interested in occultism and to deal with corresponding ideas and practices. The crisis finally culminated in piety and led him from 1892 to several monastic stays in the province and to clothing as a lay brother in the Abbey of Saint-Martin of Ligugé near Poitiers.

La Bas and the Rosicrucian Underground

Huysmans processed this development in four novels about the same protagonist, a writer named Durtal. They are: Là-bas (Over There, 1891), En route (On the Way, 1895), La Cathédrale (1898) and L’Oblat (The Lay Brother, 1903). In Là-bas Huysmans describes the religious Rosicrucian underground, which he intensively explored. The plot of the novel culminates in the detailed description of an orgiastic black mass. Huysmans, who was deeply fascinated by Satanism, was inspired by the works of many occultists, spiritualists and black magicians, some of whom led him “personally “down there in the dark realm where the devil is worshipped in obscene and bloodthirsty mass celebrations.

Later Years

A little later Huysmans retired to a Benedictine monastery in Paris, where he died of cancer in his lower jaw after long suffering. The success of A rebours was limited to an intellectual audience. Là-bas, on the other hand, was a bestseller. Huysmans’ biggest sales success with about 40 editions in 20 years became La Cathédrale, whose plot takes place in and around Chartres Cathedral. Today this novel is hardly known in comparison to Là-bas and especially. Huysmans’ work was known for his idiosyncratic use of the French language, extensive vocabulary, detailed and sensuous descriptions, and biting, satirical wit. It also displays an encyclopaedic erudition, ranging from the catalogue of decadent Latin authors in À rebours to the discussion of the iconography of Christian architecture in La cathédrale. Huysmans expresses a disgust with modern life and a deep pessimism. This had led him first to the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer.[3] Later he returned to the Catholic Church, as noted in his Durtal novels.

With jaw cancer, J.-K. Huysmans died at his Parisian home on May 12, 1907, and is buried in Paris at the Montparnasse cemetery.

Colby Smith, Neo-Decadence: A very brief Introduction, [7]

References and further Reading:

- [1] J’Accuse – Émile Zola and the Dreyfus Affaire, SciHi Blog

- [2] Oscar Wilde – One of the Most Iconic Figures of Victorian Society, SciHi Blog

- [3] The World according to Arthur Schopenhauer, SciHi Blog

- [4] Joris Karl Huysmans, website

- [5] Works by or about Joris-Karl Huysmans at Internet Archive

- [6] Joris Karl Huysmans at Wikidata

- [7] Colby Smith, Neo-Decadence: A very brief Introduction, drblackistheuniverse @ youtube

- [8] Baldick, Robert (1955). The Life of J.-K. Huysmans. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- [9] Blunt, Hugh F. (1921). “J.K. Huysmans.” In: Great Penitents. New York: The Macmillan Company

- [10] Joris Karl Huysmans, Against The Grain by Joris-Karl Huysmans, Project Gutenberg ebook

- [11] Joris Karl Huysmans, Là-bas (Down There) by J. K. Huysmans, Project Gutenberg ebook (Also known as The Damned)

- [12] Timeline for Joris Karl Huysmans, via Wikidata