Blaise Pascal (1623-1662)

On June 19, 1623, French mathematician, physicist, inventor, writer and Catholic theologian Blaise Pascal was born.

“A few rules include all that is necessary for the perfection of the definitions, the axioms, and the demonstrations, and consequently of the entire method of the geometrical proofs of the art of persuading.”

– Blaise Pascal, The Art of Persuasion (1660)

The Son of a Tax Collector

“It is not certain that everything is uncertain.” is one of the many profound insights that Blaise Pascal published in his seminal work entitled “Pensées” (Thoughts, published in 1669, after his death). He literally had versatile scientific interests, as he provided influential contributions in the field of mathematics, physics, engineering, as well as in religious philosophy. Blaise Pascal was a child prodigy educated by his father Étienne Pascal, a tax collector in Rouen. His mother died when he was only three years old. As the father did not like the way school was taught at that time he decided to instruct Blaise and his three siblings at home by himself. In particular he put emphasis on learning the classic languages Latin and Greek. But he considered not to teach geometry to Blaise because he felt the topic was too enticing and attractive.

Inventing Euclid on his own

Geometry is the branch of mathematics that deals with points, lines, angles, surfaces, and solids. Blaise’s father thought that if exposed to geometry and mathematics too soon, Blaise would abandon the study of classics. But, this ban on mathematics made Blaise even more curious. On his own he experimented with geometrical figures. He invented his own names for geometrical terms because he had not been taught the standard terms. He discovered that the sum of the angles of a triangle are two right angles and, when his father found out, he relented and allowed Blaise a copy of Euclid‘s standard textbook on mathematics. Some people believe that Blaise was twelve years old when he started attending meetings of a mathematical academy together with his father. Others suppose that he did not attend the meetings until he was about sixteen. In any case he was far younger than the adults who were there.[4]

The First Digital Calculator

Blaise Pascal invented the first digital calculator to help his father with his work collecting taxes. He worked on it for three years between 1642 and 1645. The device, called the Pascaline, resembled a mechanical calculator of the 1940s. This, almost certainly, makes Pascal the second person to invent a mechanical calculator for Wilhelm Schickard had manufactured one in 1624.[2] First, the Pascaline was only able to do additions, but was subsequently improved also to provide the means for subtractions. There were additional problems faced by Pascal in the design of his calculator due to the French currency at that time. There were 20 sols in a livre and 12 deniers in a sol. This monetary system remained in France until 1799 (in the UK a system with similar multiples lasted even until 1971). Thus, Pascal had to solve much harder technical problems to work with this division of the livre into 240 than he would have had if the division had been 100. Although Blaise Pascal filed a patent for his machine, he was not able to make a fortune out of it. The elaborate and complex design of the machine made it’s construction much too expensive to be sold in significant numbers.

Laying the Foundation for Probability Theory

In 1653 Pascal wrote a treatise on air pressure in which, for the first time in the history of science, hydrostatics is dealt with comprehensively. With his new acquaintances, especially the Chevalier de Méré, Pascal also discussed the chances of winning in gambling, a typical noble pastime. This led him in 1653 to turn his attention to probability, which he promoted in 1654 in correspondence with the Toulouse judge and great mathematician Pierre de Fermat.[3] They mainly studied dice games. At the same time he dealt with further mathematical problems and published 1654 different treatises: the Traité du triangle arithmétique on Pascal’s triangle and binomial coefficients, in which he explicitly formulated the principle of proof of complete induction for the first time, the Traité des ordres numériques on orders of numbers and the Combinaisons on combinations of numbers.

Abandoning Science

In the autumn of 1654, Pascal was struck by a depressive mood. He approached Jacqueline again, visited her frequently in the monastery and moved to another quarter to avoid his glamorous friends. After all, he continued to work on mathematical and other scientific questions. On 23 November (possibly after an accident with his carriage, which is not reliably attested) he had a religious awakening experience, which he tried to record on a preserved sheet of paper, the Mémorial, at night. He completely abandoned his scientific work and devoted himself to philosophy and theology. Two of his most famous works date from this period: the Lettres provinciales and the Pensées. The later consists of a collection of personal thoughts on human suffering and faith in God. This work contains also ‘Pascal’s wager‘ which claims to prove that belief in God is rational with the following argument.

“If God does not exist, one will lose nothing by believing in him, while if he does exist, one will lose everything by not believing.”

Last Years

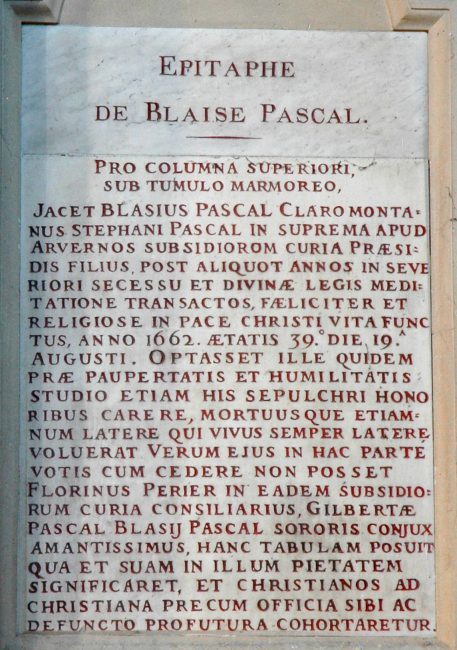

Epitaph of Pascal in the church St-Étienne-du-Mont in the 5th arrondissement of Paris

With his already poor health it went downhill faster and faster during these years, certainly also because of his extremely ascetic way of life, which weakened him additionally. So he could not work for many weeks in 1659. Nevertheless, in the same year he was a member of a committee that tried to initiate a new Bible translation. In 1660 he spent several months as a convalescent at a small castle of his older sister and his brother-in-law near Clermont. In early 1662, together with his friend Roannez, he founded a hackney carriage company (“Les carrosses à cinq sous“), which marked the beginning of public transport in Paris. In August he fell seriously ill, had his household (still quite respectable) sold for charitable purposes and died at the age of only 39.

Gregory B. Sadler, Blaise Pascal | The Wager About God’s Existence (Pensées) | Philosophy Core Concepts, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Blaise Pascal“, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- [2] Wilhelm Schickard and his Calculator Machine, SciHi Blog

- [3] Pierre de Fermat and his Last Problem, SciHi Blog

- [4] Euclid – the Father of Geometry, SciHi Blog

- [5] Blaise Pascal at zbMATH

- [6] Blaise Pascal at Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [7] “Blaise Pascal“. Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- [8] Blaise Pascal at Wikidata

- [9] Gregory B. Sadler, Blaise Pascal | The Wager About God’s Existence (Pensées) | Philosophy Core Concepts, Gregory B. Sadler @ youtube

- [10] Stephen, Leslie. . Studies of a Biographer. Vol. 2. London: Duckworth and Co. pp. 241–284.

- [11] Conner, James A. (2006), Pascal’s Wager: The Man Who Played Dice with God (1st ed.), HarperCollins

- [12] Adamson, Donald. Blaise Pascal: Mathematician, Physicist, and Thinker about God (1995)

- [13] Blaise Pascal at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [14] Simpson, David. ““Blaise Pascal”“. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [15] Clarke, Desmond. “Blaise Pascal”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [16] Timeline of 17th century Mathematicians, via DBpedia and Wikidata