Donatien Alphonse François de Sade (1740 – 1814)

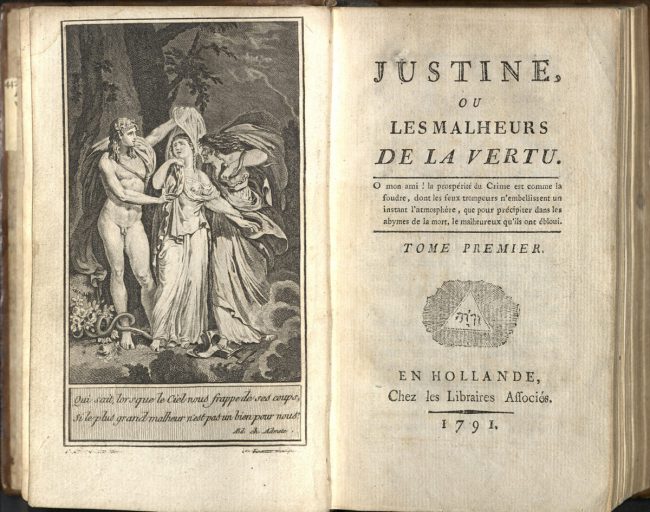

On March 6, 1801, French novelist Donatien Alphonse François de Sade, better known as the Marquis de Sade, was arrested for being the author of the anonymously published book ‘Justine or the Misfortune of Virtue‘ by order of Napoleon Bonaparte.

“…there is a sum of evil equal to the sum of good, the continuing equilibrium of the world requires that there be as many good people as wicked people…”

– Marquis de Sade, Justine or The Misfortunes of Virtue (1787)

A No Longer Rich Noble Family

The Sades were an old, albeit no longer rich noble family of Provence, which originally had the count’s title (French comte). Grandfather Gaspard-François de Sade was the first family member to use the higher title of Marquis. Donatien de Sade was born on June 2, 1740, in the Paris City Palace of the Condés, a branch of the royal family of the Bourbons, to whom his mother Marie-Eléonore de Maillé de Carman was related. His father, Jean-Baptiste-François-Joseph de Sade, a field marshal and important ambassador, had ruined his reputation at the royal court by excessively open criticism, Donatien grew up in Paris and became a Colonel fighting in the Seven Year’s War, during which he was promoted several times and won an award for bravery before the enemy.

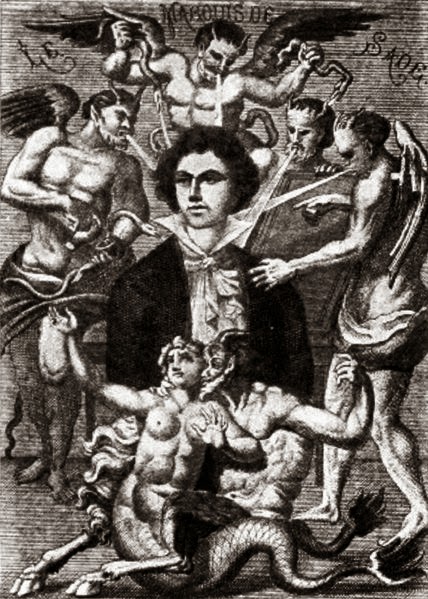

Depiction of the Marquis de Sade by H. Biberstein in L’Œuvre du marquis de Sade, Guillaume Apollinaire (Edit.), Bibliothèque des Curieux, Paris, 1912

Prostitutes and Blasphemy

“No desire can be termed outlandish, my dear; all desires can be found in nature. When nature created human beings, it delighted in differentiating their sexual leanings as much as their faces; and we should no more be astonished by the diversity of our features than by the diversity that nature has placed in our affections.”

– Marquis de Sade, Philosophy in the Bedroom (1795)

He fell in love with a rich magistrate’s daughter, but her father rejected his suitorship and, instead, arranged a marriage with his elder daughter, Renée-Pélagie de Montreuil. However, when his wife came to live at his castle in Lacoste, he began an affair with the younger sister. He was known to have had sexual relationships with prostitutes and several employees at the castle and was early accused of blasphemy. When he moved to Paris in 1763, he was put under surveillance by the police and was held in prison several times shortly. In 1764 he inherited from his father the office of the royal lieutenant general of the provinces of Bresse, Bugey, Valromey and Pays de Gex, bordering Switzerland, which was above all an honourable sinecure. His wealth acquired through marriage enabled Sade to lead a scandalous life, which was soon to go beyond the bounds of what one was prepared to accept with noble Libertins at that time. Two years later, the first major scandal occurred, when de Sade procured the sexual services of a woman who accused him of abusing and imprisoning her. Without access to the courts, de Sade was arrested and imprisoned.

The first page of Sade’s Justine, one of the works for which he was imprisoned

Fleeing from the Government

In the following years, Sade spent a lot time fleeing from the government, due to many accusations by former employees or prostitutes. On the basis of accusations by a certain Rose Keller that she had been kidnapped by him under false pretences, arrested and severely abused by flogging, Sade was arrested again in 1768. However, after Sade had paid the woman compensation, she refrained from taking legal action. However, after further accusations, he had to escape trial and execution of the sentence by fleeing to Italy. Here, after publishing the report of a trip to Holland in 1769, he also wrote a report on his trip to Italy (1775) and a book on Rome, Florence and Naples (1776).

The 120 Days of Sodom

“The Duc, pike aloft, closed in upon Augustine; he brayed, he swore, he waxed unreasonable, and the poor little thing, all atremble, retreated like a dove before the bird of prey ready to pounce upon it.”

– Marquis de Sade, The 120 Days of Sodom (1785)

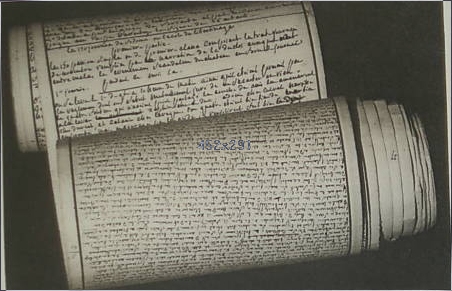

However, in 1776, Sade was tricked into going to Paris to visit his supposedly ill mother, who in fact had recently died. He was arrested there and imprisoned in the Château de Vincennes. Sade escaped and was recaptured several times. In prison he finally became an author. His central works from this period are Les cent-vingt jours de Sodome (The 120 Days of Sodom, 1782), Aline et Valcour ou Le Roman philosophique (1786) and Les Infortunes de la vertu (The Unhappy Destiny of Virtue, 1791). However, because of the religious and moral indignation of what he wrote, he wrote mostly secretly and, in order not to be conspicuous by excessive paper consumption, in tiny writing.

Original manuscript of the 120 days of Sodom of Sade (Roll of 12 meters long and 11 centimeters wide found at the Bastille.

Transferred to the Bastille

In July 1789, he was transferred to the Bastille and just before the famous storming of the Bastille, he was transferred to the mental institution of Charenton. Now that he was considered mentally ill, his wife was able to file for divorce without any loss of honor. In 1790, Sade was released and divorced shortly after.

Released and Arrested again

Enjoying his new freedom, Sade began publishing his works anonymously and met Marie-Constance Quesnet with whom he stayed together for the rest of his life. Sade began an active career in politics on the far left side and started living in Paris again. He wrote several political pamphlets and after he saved his deserting son’s neck, his name was added to the list of émigrés of the Bouches-du-Rhône department. But, despite the new troubles, Sade wrote a widely admired eulogy for Jean-Paul Marat. [4] In 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the arrest of the anonymous author of Justine and Juliette. Sade was arrested and imprisoned without trial. First, he was held in the Sainte-Pélagie prison and, following allegations that he had tried to seduce young fellow prisoners there, in the harsh fortress of Bicêtre. Two years later, he was declared insane and moved back into the asylum at Charenton along with his wife. There, he was able to stage his plays with the other inmate’s help, which were even viewed by the general public of Paris. However, he was soon deprived of pens and paper and the government suspended all theatrical performances.

Death

Marquis de Sade passed away in 1814 and his son burned all of his remaining manuscripts including the immense multi-volume work Les Journées de Florbelle. Many contemporary writers were highly fascinated by Sade’s works. Several authors published their own thoughts on Sade, like Geoffrey Gorer, who wrote a book titled ‘The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade‘ in 1935. It was found that Sade had completely opposite views on mankind than contemporary philosophers. One of the pioneers of surrealism, Guillaume Apollinaire referred to Sade as “the freest spirit that has yet existed” and others saw him as a precursor of Sigmund Freud‘s psychoanalysis in his focus on sexuality as a motive force. But also feminist readings of Sade occurred in the 20th century. Angela Carter described Sade in ‘The Sadeian Woman: And the Ideology of Pornography‘ as a “moral pornographer” who created spaces for women. Others saw him more as a “woman-hating pornographer” who supported violence against women.

Marquis De Sade’s Legacy

Throughout the years, Sade’s fiction has been tagged under many different titles, including pornography, Gothic, and baroque. However, his most famous works, ‘Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue‘, ‘Juliette‘, ‘The 120 Days of Sodom‘, and ‘Philosophy in the Bedroom‘ are considered libertine novels. These works challenge perceptions of sexuality, religion, law, age, and gender, and Sade was known to intentionally “shake the world at its core” while wishing to present “the most impure tale that has ever been written since the world exists.”

James Weiss discusses his book, the “Marquis de Sade’s Veiled Social Criticism”, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Life and Times of the Marquis de Sade

- [2] Paglia, Camille. (1990) Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson. NY: Vintage

- [3] Marquis de Sade at Britannica

- [4] Murder in the Bathtub – Jean Paul Marat and Charlotte Corday, SciHi Blog, July 13, 2012.

- [5] Marquis de Sade at Wikidata

- [6] Works by or about Marquis de Sade at Internet Archive

- [7] Œuvres du Marquis de Sade

- [8] Texts from Marquis de Sade at Wikisource

- [9] James Weiss discusses his book, the “Marquis de Sade’s Veiled Social Criticism”, Northeastern @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of Donatien Alphonse Francois de Sade, via Wikidata