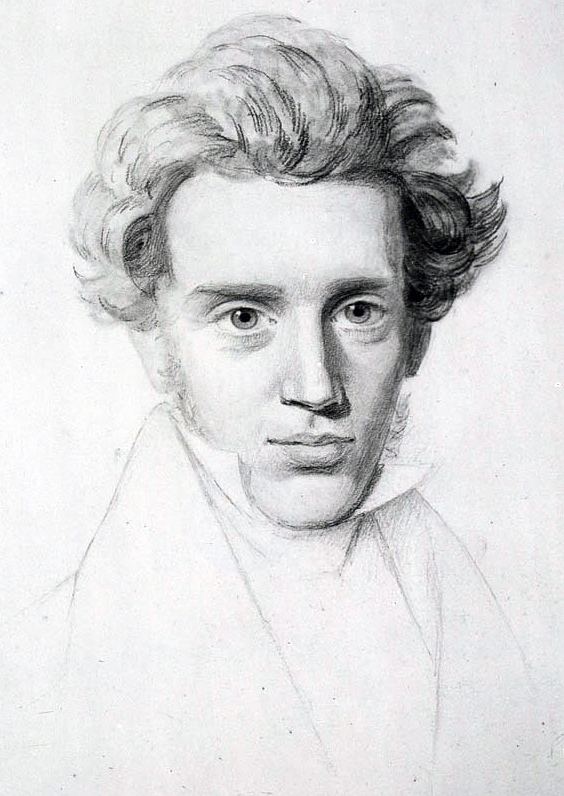

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

On May 5, 1813, Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard was born. A theologian, poet, social critic and religious author, Kirkegaard is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He is regarded as the leading Danish philosopher and also as an important prose stylist. He is one of the most important representatives of Denmark’s Golden Age.

“I must find a truth that is true for me.”

– The Journals of Soren Kierkegaard (1835)

Kierkegaard’s Life

Kierkegaard’s life is poor in external events, but rich in internal conflicts. His life as well as his intellectual work took place almost exclusively in the microcosm of the capital Copenhagen, which at that time had barely more than 100,000 inhabitants who lived densely packed within the city walls. Throughout his life, Kierkegaard was a deeply religious man, seeing himself as a follower of Christ, always introspective, internally torn apart by mental conflicts, which found expression in his extensive diary notes. All in all, the picture emerges of a melancholic, deeply melancholic human being. Kierkegaard broke off his engagement to Regine Olsen for religious reasons and never married. He hardly noticed the Schleswig-Holstein War. Kierkegaard was a great lover of opera and a frequent visitor to the famous Royal Theatre, but otherwise seems to have had little interest in art. He enjoyed a comprehensive humanistic education and was familiar with the works of Greek-Roman antiquity, but also with modern European writers and European – especially German – philosophy.

Papers of a Survivor

Søren Kierkegaard was the son of the merchant Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard (1756-1838). His father, who came from the poorest Jutland peasants, had become wealthy in Copenhagen through the wool trade. His mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard (1768-1834), was Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard’s second wife and served as a maid in his father’s household before the marriage. Of the seven children of the Kierkegaard couple, all three daughters and two sons died by 1835, so that only Søren and Peter Christian survived their father. In 1834 Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard’s wife, twelve years younger, died. These strokes of fate strengthened the belief in Kierkegaard’s father that he would be punished by God for earlier sins. Since none of the deceased children had become older than 33 years, the father believed that the two still living sons would also die early and that he would survive them (which did not happen). The title of Kierkegaard’s first paper Papers of a Survivor, published in 1838, the year of his father’s death, can only be understood against this background. Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard left his son a legacy of 30,000 imperial talers, which secured Kierkegaard’s economic existence and relieved him of the need to make his own living for the rest of his life.

Education

Kierkegaard graduated from Borgerdydskole. In 1830 he began studying philosophy at the University of Copenhagen with Poul Martin Møller and Protestant theology. Kierkegaard did not take his studies very seriously for a long time and preferred to indulge in pleasures. But it was his father’s constant admonitions and finally his death that led Kierkegaard to continue his studies seriously at the end of the 1830s. He completed his studies in 1840 with the theological state examination as a candidate of theology. In 1841 he obtained a master’s degree with a dissertation on the concept of irony with constant regard to Socrates.[2] The university panel considered it noteworthy and thoughtful, but too informal and witty for a serious academic thesis.

Regine Olsen

Regine Olsen 1840

In the spring of 1837, Kierkegaard first met 14-year-old Regine Olsen (1822-1904). Despite the age difference of ten years, both felt strongly attracted to each other. In September 1840 Kierkegaard got engaged to Regine. But only a few days after the engagement Kierkegaard began to improve his ability to make Regine happy. In August 1841 Kierkegaard ended the engagement with a letter to Regine, to which he attached the engagement ring. After the break with Regine, Kierkegaard apparently never again attempted to approach a woman. Regine Olsen’s importance for Kierkegaard’s work can hardly be overestimated. It is possible that many of his writings would not have been written without this formative episode or not in this form.

Either – Or

“It is the duty of the human understanding to understand that there are things which it cannot understand…”

– The Journals of Soren Kierkegaard (1847)

Kierkegaard published some of his works using pseudonyms and for others he signed his own name as author. Whether being published under pseudonym or not, Kierkegaard’s central writings on religion have included Fear and Trembling and Either/Or, the latter of which is considered to be his magnum opus. It was mostly written during Kierkegaard’s stay in Berlin, where he took notes on Schelling‘s Philosophy of Revelation.[1] Either/Or includes essays of literary and music criticism and a set of romantic-like-aphorisms, as part of his larger theme of examining the reflective and philosophical structure of faith. In this work, Kierkegaard describes two stages: the aesthetic and the ethical, whereby in the final part, which has the form of a sermon, already leads to the third religious stage, not yet dealt with in the work. Fear and trembling, written in a lyrical prose but not without humour and irony, is essentially a meditation on the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac. Kierkegaard affirms in this scripture that man, by entering out of the ethical sphere and into the religious sphere, as the individual stands higher than the general, i.e. the ethical, and only owes obedience to God. Abraham’s intention to sacrifice Isaac at God’s command is therefore expressly approved, even if Abraham thereby disregards ethics. At the same time it is explained that everything is possible by virtue of faith (i.e. by virtue of the absurd).

A Life in Isolation

“Most men pursue pleasure with such breathless haste that they hurry past it.”

– Soren Kierkegaard, Either/Or (1848)

Kierkegaard’s works, with the exception of the Papers of a Survivor, his dissertation and posthumously published writings, all appeared in the years 1843 to 1855. In addition to extensive walks, regular church services and visits to the Royal Theatre at Kongens Nytorv, Kierkegaard probably spent most of this period of his life working on his public works and writing diary entries. Kierkegaard spent these years in a largely isolated environment, both socially and intellectually. Kierkegaard had his works printed, without exception, at his own expense, so that he was completely independent of publishers. Apart from his debut work Either/Or, which was well received by the critics, Kierkegaard’s works were largely misunderstood by his contemporaries.

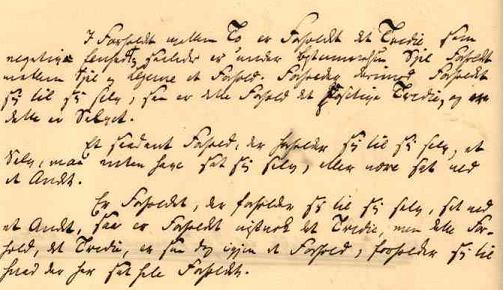

Søren Kierkegaard’s manuscript of The Sickness Unto Death, 1849.

The 1848 Revolution

In 1847, the Works of Love appeared, which deals with the problem of charity and the question of how the love revealed by Christ can be expressed in every single action. The revolution of 1848 was a historic turning point also in Denmark. Kierkegaard, who was generally not interested in politics or events of contemporary history, had only contempt for the revolution because he strongly mistrusted democratic aspirations in general. The revolution also had personal consequences for Kierkegaard, as the assets in which his legacy was invested lost much of their value. Kierkegaard, who despised (and could afford) economic activities, had made no effort to increase his inherited wealth or at least preserve its substance. He had always lived on a large scale and had not earned any income of his own – not even from his books. Kierkegaard’s last years were therefore increasingly marked by financial worries – a completely new experience for him.

Sickness Unto Death

The Second edition of Either/Or was published early in 1849. Later that year he published The Sickness Unto Death, under the pseudonym Anti-Climacus. He’s against Johannes Climacus who kept writing books about trying to understand Christianity. Here he says, “Let others admire and praise the person who pretends to comprehend Christianity. I regard it as a plain ethical task – perhaps requiring not a little self-denial in these speculative times, when all ‘the others’ are busy with comprehending-to admit that one is neither able nor supposed to comprehend it.” He now pointedly referred to the acting single individual in his next three publications; For Self-Examination, Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays, and in 1852 Judge for Yourselves!.[148][149] Judge for Yourselves! was published posthumously in 1876.

Kierkegaard’s Fight against the Church

“Is not “Christendom” the most colossal attempt at serving God, not by following Christ, as He required, and suffering for the doctrine, but instead of that, by “building the sepulchers of the prophets and garnishing the tombs of the righteous.”

– Soren Kierkegaard, Attack Upon Christendom (1855)

Kierkegaard’s last years are characterized by an increasing religious “radicalization”. The “official”, moderate, bourgeois Christianity of the Danish state church could less and less satisfy its increasing demands on the “true” Christianity. Kierkegaard screwed up the conditions which a person had to fulfil in order to be able to call himself a Christian from his point of view, so that in the end they became practically unattainable and would have deprived every organised church of its foundations. The aggressiveness of the attacks against the church and its demands on the true Christian people escalated in these last writings. He accuses the official church of not representing Christianity, but effectively preventing it. Official Christianity and its rites were a forgery, a lie, a comedy play. Kierkegaard indicates that this struggle against the Church is to be regarded as his real work and that his earlier writings are to be regarded only as preparatory tactical manoeuvres which above all served the purpose of establishing him as a serious theologian to be listened to.

On 2 October 1855, Kierkegaard suffered a stroke on the street and collapsed. He was taken to Frederik’s Hospital in Copenhagen. There he died, refusing communion, on 11 November 1855 at around 9 p.m. at the age of 42.

Arthur F. Holmes, A History of Philosophy | 68 Historical Roots of Existentialism: Kierkegaard, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and the German Idealism, SciHi Blog

- [2] Socrates and the Socratic Method, SciHi Blog

- [3] Works by or about Søren Kierkegaard at Internet Archive

- [4] Works by or about Soren Kierkegaard at Wikisource

- [5] Kierkegaard”, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Jonathan Rée, Clare Carlisle & John Lippitt (In Our Time, Mar. 20, 2008)

- [6] Soren Kierkegaard at Wikidata

- [7] Soren Kierkegaard at the Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

- [8] Google Doodle for Soren Kierkegaard’s 200th Birthday

- [9] Soren Kierkegaard, Danish philosopher, at Britannica Online

- [10] Soren Kierkegaard at the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

- [11] Arthur F. Holmes, A History of Philosophy | 68 Historical Roots of Existentialism: Kierkegaard, wheatoncollege @ youtube

- [12] Hohlenberg, Johannes (1954). Søren Kierkegaard. Translated by T.H. Croxall. Pantheon Books.

- [13] Mackey, Louis (1971). Kierkegaard: A Kind of Poet. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- [14] Wyschogrod, Michael (1954). Kierkegaard and Heidegger. The Ontology of Existence. London: Routledge.

- [16] Timeline for Soren Kierkegaard, via Wikidata