Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), Portrait by John Michael Wright

On December 4, 1679, Thomas Hobbes passed away. The philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment and the political theorist of the Absolutism is probably best known for his 1651 book Leviathan that established the foundation for most of Western political philosophy from the perspective of social contract theory.

“I know not how the world will receive it, nor how it may reflect on those that shall seem to favor it. For in a way beset with those that contend, on one side for too great Liberty, and on the other side for too much Authority, ’tis hard to passe between the points of both unwounded.”

— Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, The Epistle Dedicatory, Paris, April 15-25, 1651.

Thomas Hobbes Background

Thomas Hobbes was born in Malmesbury in the county of Wiltshire, England, the son of a simple country priest, in politically difficult times, because of the invasion of the Spanish Armada. Hobbes’ family faced times of fear and uncertainty due to the conflicts between the king and the parliament as well as the disputes between the many social groups. These events depicted a great influence in Hobbes’ views and philosophies. Thomas Hobbes was a child prodigy, his enormous talents in logics and mathematics favored his educational development and he was able to attend an affiliated institute of the Oxford University at only 14 years.

After graduating from Oxford in 1608 with a bachelor’s degree, he became a tutor to the noble Cavendish family. He held this post with interruptions until the end of his life. He taught William Cavendish, who later became Count of Devonshire. His work as an educator in one of England’s leading noble families, which was to support him throughout his life, gave him the opportunity to travel extensively and to make contact with leading politicians and thinkers of his time. For a short time Hobbes was secretary of the philosopher Francis Bacon,[6] for whom he translated some of his writings into Latin. The work for Bacon, the founder of English empiricism, is said to have had some influence on the mechanical-materialistic conception of his philosophy.

It was during Hobbes’ third journey through Europe when he developed his plan to divide his philosophies into three different parts: ‘De Cive‘, ‘De Corpore‘, and ‘De Homine‘. After being exiled due to his support of King Charles I, Hobbes again tried to influence England’s political situation in favor of the absolute monarchy with ‘De Cive‘, which he published in 1642.

Leviathan

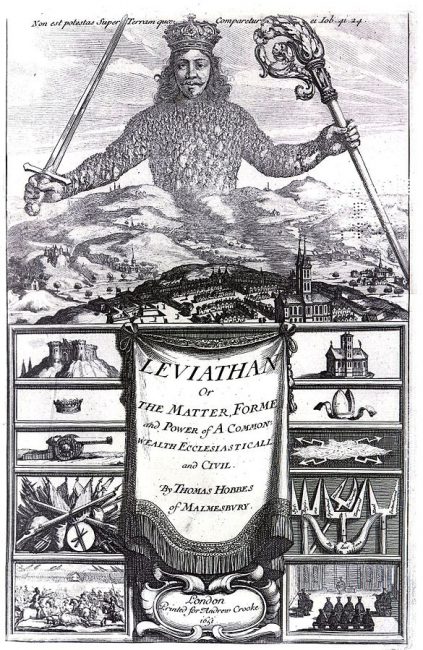

Hobbes’ most famous work, ‘Leviathan‘ was published in 1651 and consists of four major parts: ‘Of Man’, ‘Of Common-wealth’, ‘Of a Christian Common-wealth’, and ‘Of the Kingdom of Darkness’. The goal Hobbes’ was to lay a scientific foundation for politics based on rational principles. The work is seen as revolutionary in the sense of social contract theory, Hobbes listed arguments for a social contract and a rule by an absolute sovereign.

“Science is the knowledge of Consequences, and dependence of one fact upon another: by which, out of that we can presently do, we know how to do something else when we will, or the like, another time:”

— Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, The First Part, Chapter 5, p. 21.

In the first part ‘Of Man’, Hobbes developed a state of nature, in which a society exists without laws, a government, and is free of restrictions by morals, traditions, and religion. To Hobbes, a state of ‘bellum omnium, contra omnes‘ is present and every individual is characterized by demands, fear, and reason. Hobbes does not picture the human being as malicious, but indeed as antisocial. Also, the individuals have, according to Hobbes, the ambition of self-preservation in the state of nature and only through the decision by the individuals to develop a political organ they can overcome the state of nature and evolve a government.

The frontispiece of the book Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes; engraving by Abraham Bosse

In the chapter ‘Of Common-wealth’, Hobbes explains that laws based on reason are not enough to establish peace, wherefore an almighty authority was to be appointed, which was to sanction the individual’s actions. Through a contract, every citizen (except for the unrestricted sovereign) was to renounce from any kind of power in the society in favor of a single person or group, which would end the state of nature. Hobbes’ theories differ in many aspects from the ideas by Aristoteles, who understood a society’s goal as an ‘eudaimonia‘ (good life). Hobbes saw in contrast a common-wealth’s goal as ‘summum malum‘ (the prevention of the worst evil).

The first two parts are seen as the most important and most influential chapters of the work. The last two illustrate Hobbes’ ideas concerning the philosophy of religion as well as church politics.

Hobbes’ Life after Leviathan

Through his work, Hobbes had to face criticism from various social groups. The church criticized his support for an independent constitution of the church and his materialism, and the liberalists disliked his idea of an almighty sovereign. After the publication of his main work, the Leviathan, Hobbes was often hosted in England by the Church, the nobility and private individuals for the alleged atheistic and heretical character of his work. Numerous friends broke with him, but state power left him largely unchallenged. This might have been connected in particular with the fact that he stood up – against Anglicans and Presbyterians – for the church constitution favored by Cromwell and the Puritans, independentism. In 1655 and 1658 De Corpore and De Homine, the two missing parts of his system, appeared.

However, after the restoration of the Stuart royalty in 1660, the situation became more acute for him. Especially after the Great Plague and the fire of London,[7] he was persecuted by Anglican and Presbyterian circles, especially by the new ministers Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon and Gilbert Sheldon. In order to be able to prosecute him for alleged heresy, several attempts were even made to create a legal basis specifically for this. Thanks to influential friends, such as the Earl of Arlington, who held a ministerial post in the Cabal government, Hobbes managed to survive the intrigues directed against him unscathed. He was also protected by the sympathy of King Charles II, who had secretly converted to Catholicism anyway.

The history of the civil war epoch Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Counsels and Artifices by which they were carried on from the year 1640 to the year 1662, written in 1668, received no printing permission, and Hobbes had to have his Latin writings published in Amsterdam. Nevertheless, until his death he lived in secure and comfortable conditions on a country estate belonging to the friendly Cavendish family. In 1679, the year of his death, a strong parliament enforced his ideas in the habeas corpus act against Charles II. His final works were an autobiography in Latin verse in 1672, and a translation of four books of the Odyssey into “rugged” English rhymes that in 1673 led to a complete translation of both Iliad and Odyssey in 1675.

On December 4, 1679, Thomas Hobbes passed away in Derbyshire, England.

Ivan Szelenyi, 2. Hobbes: Authority, Human Rights and Social Order, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Thomas Hobbes at Stanford

- [2] Thomas Hobbes

at Wikidata

- [3] Thomas Hobbes Timeline via Wikidata

- [4] Montesquieu and the Separation of Powers, SciHi Blog

- [5] Robert Malthus and the Principle of Population, SciHi Blog

- [6] Sir Francis Bacon and the Scientific Method, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Great Fire of London, SciHi Blog

- [8] Ivan Szelenyi, 2. Hobbes: Authority, Human Rights and Social Order, Foundations of Modern Social Thought (SOCY 151), YaleCourses @ youtube

- [9] Williams, Garrath. “Thomas Hobbes: Moral and Political Philosophy.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [10] Lloyd, Sharon A., and Susanne Sreedhar. [2002] 2018. “Hobbes’s Moral and Political Philosophy.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [11] Robertson, George Croom; Anonymous texts (1911). “Hobbes, Thomas“. In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 545–552.

- [12] Hinnant, Charles H. (1980). Thomas Hobbes: A Reference Guide, Boston: G. K. Hall & Co.

- [13] Montmorency, James E. G. de (1913). “Thomas Hobbes”. In Macdonell, John; Manson, Edward William Donoghue (eds.). Great Jurists of the World. London: John Murray. pp. 195–219.

- [14] Works of or about Thomas Hobbes, via Wikisource

thanks for sharing..

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #25 | Whewell's Ghost