Sir Joseph Paxton (1803-1865), painting by Octavius Oakley, c. 1850

On August 3, 1803, English gardener, architect and Member of Parliament Sir Joseph Paxton was born. He is best known for designing The Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition in 1851.

The Youth of a Gardener

Joseph Paxton was born in Milton Bryne in Bedfordshire. His father William (1759-1810) and his mother Anne (1761-1823) were small farmers and had to raise their nine children with minimal financial means under the harsh conditions of the pre-industrial era. Although education in agricultural families at the time was not highly valued and children usually had to work in the fields at an early age, Joseph Paxton most likely attended primary school in nearby Woburn, established by the 1st Duke of Bedford. After the surprising death of his father, the then seven-year-old Joseph was raised by his eldest brother, also William. When the latter was entrusted in 1816 with the administration of the estate of John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, in the Battlesden Park in Woburn, he employed his younger brother as a gardener. However, Paxton was so thrilled to start working in the Duke’s gardens and arrived early in the morning while the Duke was on a journey in Russia. Paxton immediately began working, handing out tasks and it is is said that he finished his first morning’s work by 9am. At Battlesden Park, Paxton was able to gain his first experience in the field of botany.

The Duke’s Headgardener

In 1821 the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) rented the Chiswick Gardens near the Chiswick estate from William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), to create a botanical experimental garden. At the age of 20 Joseph Paxton applied to the RHS and was responsible for part of the Chiswick Gardens as a gardener. As he had not yet reached the minimum age for admission to the Society at that time, he stated his year of birth as 1801 – a false statement which can still be found in some literature about Paxton today. The Duke took regular walks through the Chiswick Gardens and was so enthusiastic about Paxton’s work that in 1826 he offered him a position as head gardener in one of his other estates – Chatsworth House, which had one of the finest parks of its time. Despite the different social backgrounds, a deep friendship developed between Cavendish and the simple gardener Joseph Paxton.

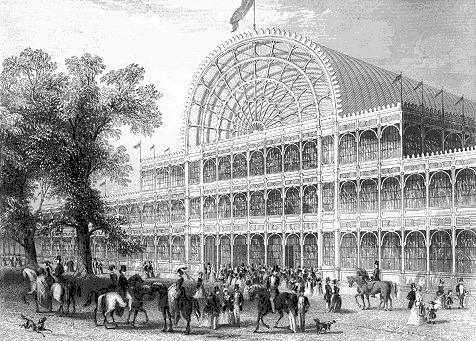

The Crystal Palace from the northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Chatsworth Gardens

On 9 May 1826 Paxton began work at Chatsworth Gardens near Bakewell in Derbyshire, where he met the housekeeper’s niece, Miss Sarah Bown (1800-1871), and married her a year later. As the Chatsworth House was extended by a new north wing at that time, Joseph Paxton’s work consisted of replanting the surrounding park. He perfected the imitation of rock gardens and water cascades, making them almost indistinguishable from natural ones. Due to his outstanding achievements, he was also appointed main forester in 1829. He established a pinetum, a collection of various coniferous plants, which was later expanded into an arboretum with deciduous trees. During this period he tested methods of transplanting large, growing trees. A milestone was the transport of several palm trees by horse-drawn carriage from Walton-on-Thames to Chatsworth, the largest of which weighed over twelve tons.

Glass Houses

In the early 1830’s Paxton began experimenting with glass houses, which were to be the forerunners of green houses. He designed constructions with the exact angles to make optimal use of the morning and evening sun. In 1836, the first Victoria amazonica, a large water lily was sent to England, but they would not grow and not flower so one seedling was sent to Paxton. Under his observation, his gardeners managed to grow the plant successfully and got it to flowering not much later. Since it continued growing, Paxton had to build another, much larger green house, later known as the Victoria Regia House. His experimentation resulted in a glass house that later depicted a great inspiration for his famous Crystal Palace.

The Great Exhibition of 1851

In the next years, Paxton built even larger and more astonishing green houses and gained a great reputation. For the Great Exhibition in 1851,[6] Paxton was given the task to design the Crystal Palace. This building made him famous. It was built by only 2000 people in eight months and demonstrated England’s technology and style. Paxton and his colleagues, Charles Fox and William Cubitt were knighted for their achievements after the Exhibition.

Main facade and transept of the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park

The Crystal Palace

Basic unit of the palace were squares of 7.3 m. The base area consisted of 77 × 17 such basic units. The division of the exhibition rooms was reflected in these units. The rooms are composed of a multiple of these basic units. Only the technical innovations of the industrial revolution and the progress in iron production made the construction of the Crystal Palace possible. The construction of iron girders also made it possible to completely dispense with load-bearing brickwork, so that large glass windows could be used instead. The first column of the building was erected on 26 September 1850. After only four months, the area in southern Hyde Park was covered with buildings on an area of 560 × 137 metres; 83,600 m² of glass, 372 roof trusses, 38 km of valley profile material, 330 km of glass frames and 17,000 m³ of wood were used After the exhibition, the building was dismantled, rebuilt with some modifications in Sydenham in the middle of a large park and used as a museum and exhibition building. Several life-size dinosaur sculptures created from 1853 onwards were erected in the park, triggering a first wave of dinosaur interest. Many sports activities developed in the park, which explains the name of the famous football club Crystal Palace. The Crystal Palace burnt down completely after an explosion on 30 November 1936. Only two towers deformed by the fire remained standing for the time being. They were removed during the Second World War because it was feared that they could serve as landmarks for enemy aircraft. The northern tower was blown up in 1941, the southern one conventionally demolished because of its proximity to other buildings. The park still exists and has been included in the register of historically interesting parks by the English Heritage.

Later Years

In December 1854 Paxton became a House of Commons deputy for the Coventry constituency. After the import duties on silk from France were lifted, unemployment rose rapidly in Coventry, which at the time was largely dependent on the silk industry. In his role as a politician, Joseph Paxton was able to attract employers from other industries and create jobs in the cotton industry thanks to his good business relations. He later advocated the construction of the Thames Graving Docks. After the death of the Duke of Devonshire in 1858, Joseph Paxton laid down his duties at the Dukes’ estate, but was allowed to remain in his house at Chatsworth Gardens. During his years as an architect and politician, Joseph had to struggle with health problems time and again. When his condition deteriorated further in 1865, he had to resign completely from his parliamentary function and died on 8 June 1865.

Making and Running Great Gardens 1700-1900 – Professor Sir Roderick Floud, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Joseph Paxton Biography at Victorian Web

- [2] Joseph Paxton at BBC History

- [3] The Late Duke of Devonshire and Sir Joseph Paxton

- [4] Paxton at Wikidata

- [6] The Great Exhibition and the Crystal Palace, SciHi Blog

- [7] Making and Running Great Gardens 1700-1900 – Professor Sir Roderick Floud, Gresham College @ youtube

- [8] George F. Chadwick, 1961, The Works of Sir Joseph Paxton 1803–1865, Architectural Press

- [9] Paxton Timeline via Wikidata:

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #51 | Whewell's Ghost