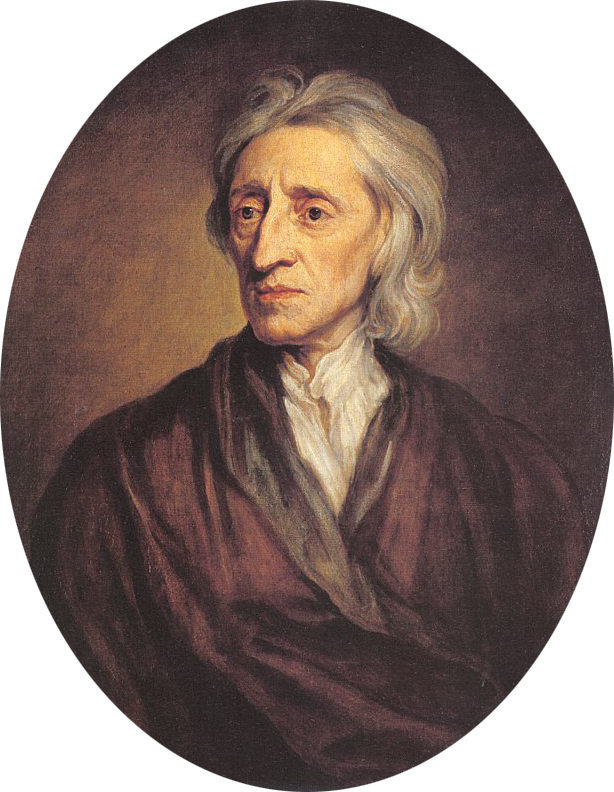

John Locke (1632-1704)

On August 29, 1632, English philosopher and physician John Locke was born. One of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers he became known as the “Father of Classical Liberalism“. He spent over 20 years developing the ideas he published in his most significant work, Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) which analyzed the nature of human reason, and promoted experimentation as the basis of knowledge.

“To love truth for truth’s sake is the principal part of human perfection in this world, and the seed-plot of all other virtues.”

— John Lock, Letter to Anthony Collins (29 October 1703)

John Locke’s Youth and Education

John Locke was born in Wrington, Somerset, England, to John and Agnes Lock, the father a country lawyer and clerk to the Justices of the Peace in Chew Magna. Both parents were Puritans. Locke grew up in a rural Tudor house in Belluton. In 1647, he was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London under the sponsorship of Alexander Popham, a member of Parliament and his father‘s former commander. After completing his studies there, he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford in 1652. At Christ Church, perhaps Oxford‘s most prestigious school, Locke immersed himself in logic and metaphysics, as well as the classical languages. Irritated by the undergraduate curriculum of the time, Locke found the works of modern philosophers, such as René Descartes, much more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. Nevertheless, Locke was awarded a bachelor‘s degree in 1656 and a master‘s degree in 1658.

The Earl of Shaftesbury

In 1666, he met the parliamentarian Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who had come to Oxford seeking treatment for a liver infection. Cooper was impressed with Locke and persuaded him to become part of his retinue. In 1667, Locke moved into Shaftesbury’s home at Exeter House in London, to serve as Lord Ashley’s personal physician. In London, Locke resumed his medical studies under the tutelage of Thomas Sydenham,[6] who had a major effect on Locke’s natural philosophical thinking.

Locke’s medical knowledge was put to the test when Shaftesbury’s liver infection became life-threatening, but was able to save his life. Shaftesbury then credited Locke for his new flourishing life. For the next two decades, Locke’s fortunes were tied to Shaftesbury, who was first a leading minister to Charles II and then a founder of the opposing Whig party. [3]

“New opinions are always suspected, and usually opposed, without any other reason but because they are not already common.”

— John Lock, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), Dedicatory epistle

Shaftsbury’s stature grew, so did Locke’s responsibilities. He assisted in his business and political matters, and after Shaftsbury was made chancellor, Locke became his secretary of presentations. During this time, Locke served as Secretary of the Board of Trade and Plantations and Secretary to the Lords Proprietor of Carolina, which helped to shape his ideas on international trade and economics. Following Shaftesbury’s fall from favour in 1675, Locke spent some time travelling across France. He returned to England in 1679 when Shaftesbury’s political fortunes took a brief positive turn. Around this time, most likely at Shaftesbury’s prompting, Locke composed the bulk of the Two Treatises of Government. While it was once thought that Locke wrote the Treatises to defend the Glorious Revolution of 1688, recent scholarship has shown that the work was composed well before this date. The work is now viewed as a more general argument against absolute monarchy and for individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy. Though Locke was associated with the influential Whigs, his ideas about natural rights and government are today considered quite revolutionary for that period in English history.

Locke’s Ideas of Freedom and Religion

Locke’s ideas on freedom of religion and the rights of citizens were considered a challenge to the King’s authority by the English government and in 1682 Locke went into exile in Holland. It was here that he completed An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, and published Epistola de Tolerantia in Latin. The English government tried to have Locke, along with a group of English revolutionaries with whom he was associated, extradited to England. Locke’s position at Oxford was taken from him in 1684.[2] Locke remained in the Netherlands until February 1689, when he returned with Mary who was about to be crowned with her husband William of Orange in the wake of the Glorious Revolution. The bulk of Locke’s publishing took place upon his return from exile.

“The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.”

— John Lock, Second Treatise of Government, (1689) Ch. II, sec. 6

Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) outlined a theory of human knowledge, identity and selfhood. To Locke, knowledge was not the discovery of anything either innate or outside of the individual, but simply the accumulation of “facts” derived from sensory experience. To discover truths beyond the realm of basic experience, Locke suggested an approach modeled on the rigorous methods of experimental science.[3] The new government of England offered Locke the post of ambassador to Berlin or Vienna in recognition of his part in the revolution, however Locke declined the honorable position. In 1691 Locke responded to financial difficulties in the government by publishing Some Considerations of the Consequences of Lowering of Interest, and Raising the Value of Money, and in 1695 Further Considerations on the topic of money. In 1693 he published Some Thoughts Concerning Education, and in 1695 The Reasonableness of Christianity.

Locke’s close friend Lady Masham invited him to join her at the Mashams’ country house in Essex. Although his time there was marked by variable health from asthma attacks, he nevertheless became an intellectual hero of the Whigs. He helped steer the resurrection of the Board of Trade, which oversaw England’s new territories in North America. Locke served as one of the body’s key members. Long afflicted with delicate health, Locke died on October 28, 1704.[1]

John Locke vs. Thomas Hobbes

Locke exercised a profound influence on political philosophy, in particular on modern liberalism. He had a strong influence on Voltaire who called him “le sage Locke“.[5] His arguments concerning liberty and the social contract later influenced the written works of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and other Founding Fathers of the United States. Locke’s political theory was founded on social contract theory. Unlike Thomas Hobbes,[4] Locke believed that human nature is characterized by reason and tolerance. Like Hobbes, Locke believed that human nature allowed people to be selfish. This is apparent with the introduction of currency. In a natural state all people were equal and independent, and everyone had a natural right to defend his “Life, health, Liberty, or Possessions“. Like Hobbes, Locke assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not enough, so people established a civil society to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government in a state of society. However, Locke never refers to Hobbes by name and may instead have been responding to other writers of the day. Locke also advocated governmental separation of powers and believed that revolution is not only a right but an obligation in some circumstances. These ideas would come to have profound influence on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

Daniel Bonevac, John Locke’s Empiricism, Introduction to Philosophy, Fall 2017 [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] John Locke at Biographies.com

- [2] John Locke Biography at European Graduate School

- [3] John Locke at History.com

- [4] Man is Man’s Wolf – Thomas Hobbes and his Leviathan, SciHi Blog

- [5] Voltaire – Libertarian and Philosopher, SciHi Blog

- [6] Thomas Sydenham – the English Hipocrates, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works by or about John Locke at Internet Archive

- [8] Works by or about John Locke, via Wikisource

- [9] “John Locke”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [10] Rickless, Samuel. “Locke on Freedom”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [11] Anstey, Peter, John Locke and Natural Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2011.

- [12] Daniel Bonevac, John Locke’s Empiricism, Introduction to Philosophy, Fall 2017, Daniel Bonevac @ youtube

- [13] John Locke at Wikidata

- [14] Timeline for John Locke, via Wikidata

Pingback: The NRA Has Helped Trump to Believe – The Daily Angle

Pingback: The NRA Has Made Trump a Believer – My Desk News

Pingback: The NRA Has Helped Trump to Believe – Onipolitics