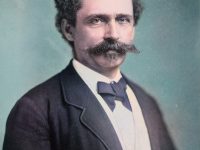

Giambattista Vico (1668-1744)

On June 23, 1668, Italian political philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist Giambattista Vico was born. An apologist of classical antiquity, Vico is best known for his magnum opus, the Scienza Nuova of 1725, often published in English as The New Science, in which he attempted to bring about the convergence of history, from the one side, and the more systematic social sciences, from the other, so that their interpenetration could form a single science of humanity. Vico is a precursor of systemic and complexity thinking, as opposed to Cartesian analysis and other kinds of reductionism.

“Verum esse ipsum factum” (“What is true is precisely what is made”)

– Giambattista Vico, On the Most Ancient Wisdom of the Italians (1710)

Giambattista Vico – Early Years

Born as the only child of Antonio and Candida Victo, a bookseller and the daughter of a carriage maker in Naples, Italy, Giovanni Battista Vico attended a series of grammar schools, but ill-health and dissatisfaction with Jesuit scholasticism led to home schooling. After a bout of typhus in 1686, Vico accepted a tutoring position in Vatolla, south of Salerno, that would last for nine years. He graduated at the University of Naples in 1694 as Doctor of Civil and Canon Law. But, as he reports in his autobiography Vita di Giambattista Vico, he considered himself as “teacher of himself,” a habit he developed under the direction of his father, after a fall at the age of 7 caused a three year absence from school.[1]

In 1699, he married a childhood friend, Teresa Destito, with whom he had eight children, and took a chair in rhetoric at the University of Naples. Throughout his career, Vico would aspire to, but never attain, the more respectable chair of jurisprudence. In 1734, however, he was appointed royal historiographer by Charles III, king of Naples, and was offered a salary far surpassing that of his professorship. Vico retained the chair of rhetoric until ill-health forced him to retire in 1741.

Title page of Principj di Scienza Nuova (1744 ed.)

A Lack of Professional Recognition

In his own time Vico‘s work was largely neglected and generally misunderstood – he described himself living quite unknown in his native city, and it was not until the nineteenth century that his thought began to make a significant impression on the philosophical world. His lack of recognition and success in his professional work, as well as personal misfortunes, made him a bitter man who was periodically subject to melancholia.[2] Vico is best known for his verum factum principle, first formulated in 1710 as part of his De antiquissima Italorum sapientia, ex linguae latinae originibus eruenda (1710, On the most ancient wisdom of the Italians, unearthed from the origins of the Latin language). The principle states that truth is verified through creation or invention and not, as per Descartes – being his prime intellectual enemy -, through observation:

“The criterion and rule of the true is to have made it. Accordingly, our clear and distinct idea of the mind cannot be a criterion of the mind itself, still less of other truths. For while the mind perceives itself, it does not make itself.”

Objecting Descartes

Vico objected to Descartes’s belief that man was everywhere, always, and equally rational. In his view, rationality was a historical acquisition, not a constant component of human nature.[3,6]

“Men first feel, necessity, then look for utility, next attend to comfort, still later amuse themselves with pleasure, thence grow dissolute in luxury, and finally go made and waste their substance.”

— Giambattista Vico, The New Science 241 (1744)

The New Science

Vico urged the study of language, mythology, and tradition as techniques for the investigation of history. In 1725, Vico published The New Science, as part of a treatise on universal law, being his major work which has been highly influential in the philosophy of history, and for historicists like Isaiah Berlin and Hayden White. As a philosopher, Vico believed that every period in history had a distinct character, and that similar periods recur throughout history in the same order. But, in contrary to the old cyclical theories of history, he asserted that these periods do not recur in exactly the same form, but are subject to the modifications that new circumstances and developments impose. Thus the historian can never be a prophet.[4] In Scienza Nuova Vico established how early civilization developed a sensus communis or collective sense. He concludes that “first, or vulgar, wisdom was poetic in nature.”, which is not an aesthetic observation, but rather points to the capacity for early humans to make meaning via comparison and to reach a communal understanding of their surroundings. Thus, the metaphors that define the poetic age also represent the first civic discourse and held, though in altered form, for subsequent formative ages, including early Greek, Roman, and European civilizations. Thus in his Scienza Nuova, Vico formulated a historical analysis of civil societies, and each society‘s relation to the respective ideas of their time.[5]

Discovery of the True Homer

Vico’s theory on the emergence of Homer‘s Iliad and Odyssey (section “Discovery of the True Homer” in Scienza Nuova) is also unusual for his contemporaries: since the vulgar feelings and customs in the heroic age corresponded to a wild and irrational state, Homeric poetry could not be the esoteric wisdom of an individual, but rather represented the poetic abilities of the Greek people as a whole. The poet of Iliad and Odyssey never existed (as an individual); rather, the Greek singers as a whole imagined the ideal of one poet.

Giambattista Vico died on January 23, 1744, in Naples, at age 75.

The Philosophy of Giambattista Vico New Science Lecture 1, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Bertland, Alexander. “Giambattista Vico (1668—1744)”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [2] Giambattista Vico at Encyclopedia of World Biography.

- [3] Vico, Giovanni Battista. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 1968. Encyclopedia.com.

- [4] Giovanni Battista Vico at infoplease.com

- [5] Giambattista Vico in The New World Encyclopedia

- [6] Cogito Ergo Sum – René Descartes, SciHi Blog

- [7] Giambattista Vico at Wikidata

- [8] Works by or about Giambattista Vico at Internet Archive

- [9] Vico’s Historical Mythology

- [10] The Philosophy of Giambattista Vico New Science Lecture 1, Chad A Haag Ecological Hermeneutics @ youtube

- [11] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [12] “Giambattista Vico” entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [13] Timeline of Early Modern Philosophers, via DBpedia and Wikidata