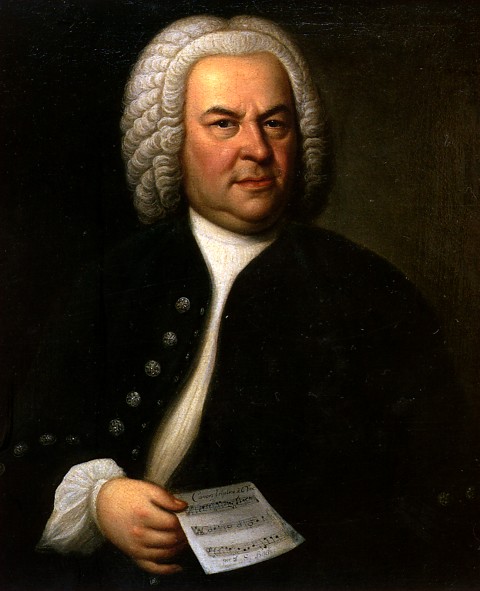

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) in a portrait by Elias Gottlob Haussmann (1746)

On July 28, 1750, one of the most important and productive composers of the Baroque period, Johann Sebastian Bach died. Bach‘s abilities as an organist were highly respected throughout Europe during his lifetime, although he was not widely recognised as a great composer until a revival of interest and performances of his music in the first half of the 19th century.

The Youngest of Eight Children

The works of Johann Sebastian Bach are considered the utmost expression of polyphony. He is probably the only composer ever to make full use of the possibilities of art available in his time. Bach was born on March 21, 1685, in Eisenach, Germany, in a Lutheran family of at least seven generations of musicians, cantors, organists, town whistlers, members of court or clavichord/harpsichord and lute makers. As the youngest of eight children, Bach received violin lessons from his father. He also had a beautiful voice and sang in the church choir. At age ten after the death of his parents, Johann Sebastian moved to the city of Ohrdruf, Germany, to live with his brother, Johann Christoph, who was the organist at St. Michael’s Church. From him Johann Sebastian received his first instruction on keyboard instruments. At the latest here his interest for music and instruments must have developed. Bach also learned to play the organ in Ohrdruf and gained a deeper understanding of the construction and mechanics of the instrument – probably from 1697 onwards through the many repairs to the organ of the Michaeliskirche, in which his brother Christoph also participated.

Organist in Arnstadt

After the unexpected loss of their “free tables” at the Ohrdruf lyceum, 14-year-old Bach and his classmate Erdmann decided to continue their school education at the particular school of the Michaeliskloster in Lüneburg. The academic level at the particular school in Lüneburg was higher than at the Ohrdrufer Lyceum. In addition, the pupils got to know the basis of the courtly tradition through the neighbourhood of the knight’s school. After graduation in 1703 Bach was hired as an organist in a church in Arnstad, Germany, which gave him time to practice on his favorite instrument and to develop his talent. He got into trouble on several occasions, once for fighting with a fellow musician and once for being caught entertaining a “strange maiden” in the balcony while he was practicing the organ. Some months later Bach upset his employer by a prolonged absence from Arnstadt: having obtained a leave permission for four weeks he had been absent for around four months in 1705–1706 to visit the organist and composer Dieterich Buxtehude in the northern city of Lübeck. The visit to Buxtehude involved a 450-kilometre journey each way, reportedly on foot.

Court Organist in Weimar

After his marriage with his cousin Maria Barbara Bach, he started a new position as court organist to Duke Wilhelm Ernst in Weimar in 1708. The years 1708 to 1710 saw an enormous output of original organ music by Bach. His reputation at the time, however, came mainly from his organ playing, not his compositions. Crown Prince Frederick of Sweden, who heard Bach play in 1714, was so astonished that he took a diamond ring from his finger and gave it to the organist. Bach’s time in Weimar was the start of a sustained period of composing keyboard and orchestral works. He attained the proficiency and confidence to extend the prevailing structures and to include influences from abroad. He learned to write dramatic openings and employ the dynamic motor rhythms and harmonic schemes found in the music of Italians such as Vivaldi, Corelli, and Torelli. Bach absorbed these stylistic aspects in part by transcribing Vivaldi’s string and wind concertos for harpsichord and organ; many of these transcribed works are still regularly performed.

Moving to Cöthen

In 1716 Prince Leopold of Cöthen, heard of Bach and offered him a position. When Bach requested his release to go to Cöthen, Duke Wilhelm refused to accept such short notice. Bach, who had already accepted an advance in salary, became so angry that he was placed under arrest and jailed for almost a month. Bach began his duties at Cöthen after his release, where he produced his greatest instrumental and orchestral works. On 7 July 1720, while Bach was away in Carlsbad with Prince Leopold, Bach’s wife suddenly died. The following year, he met Anna Magdalena Wilcke, a young, highly gifted soprano sixteen years his junior, who performed at the court in Cöthen; they married on 3 December 1721.

Cantor in Leipzig

In 1723 he was named cantor (choir leader) of Leipzig. But, the Leipzig committee was reluctant to hire him, because his reputation was mainly as an organist, not as a composer, and his ability as an organist was not needed since the cantor was not required to play at the services. His duties were primarily to provide choral music for two large churches, St. Thomas and St. Nicholas. For Christmas 1723 Bach wrote the second version of the Magnificat in E flat major with the Christmas inlays, for Good Friday 1724 his most comprehensive work to date, the St. John Passion, for Christmas 1724 a Sanctus. Probably at the beginning of 1725 Bach met the lyricist Christian Friedrich Henrici alias Picander, who finally delivered the text for the St. Matthew Passion, which was first performed in 1727 or 1729.

The Collegium Musicum

In 1729 Bach took over the direction of the Collegium musicum founded by Telemann in 1701, which he kept until 1741, perhaps even until 1746. With this student ensemble he performed German and Italian instrumental and vocal music, including his own concerts in Weimar and Köthen, which he later adapted into harpsichord concerts with up to four soloists.

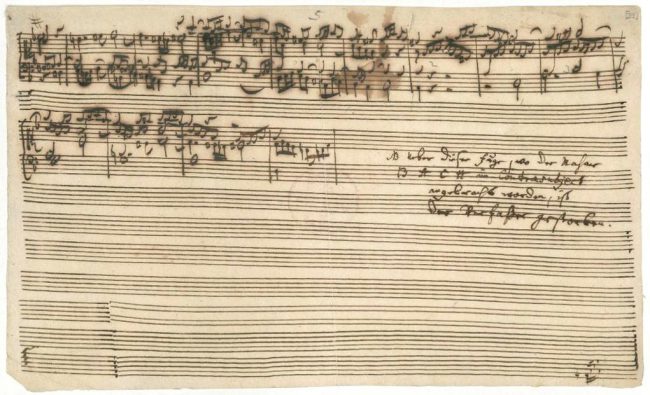

Autograph of the end of the unfinished last fugue from the Art of Fugue with Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s addition:

“NL above this fugue, where the name BACH was placed in the contrasubject, the writer has died.”

Later Years

In his later years, Bach gradually lost his eyesight and he was totally blind the last year of his life. A few days before his death he read parts of the hymn Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich allhier (Before Thy Throne I Stand) for his son-in-law to write down. Following a stroke and a high fever, Johann Sebastian Bach died on July 28, 1750 and was buried three days later at Johannisfriedhof in Leipzig.

Late Fame

During his lifetime, Bach’s compositional work received only limited attention, compared, for example, with that of his contemporaries Georg Friedrich Händel and Georg Philipp Telemann. After Bach’s death there was at first hardly any desire to continue to perform his works. The musical taste of the time longed for a “natural” and “sensitive” style of music. Bach’s music was often perceived as artificial and unnatural. The first striking turning point in the perception and appreciation of Bach’s work is the Bach biography of Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749-1818). Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy,[4] a pupil of Carl Friedrich Zelter and only 20 years old at the time, deserves the credit of having brought Johann Sebastian Bach back to the attention of a broad public almost eighty years after his death – with the revival of the St Matthew Passion in an abridged version on 11 March 1829 with the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin, founded in 1791. He thus gave an enormous impetus to the publicity of Bach’s music and initiated the Bach Renaissance.

Craig Wright, Lecture 16. Baroque Music: The Vocal Music of Johann Sebastian Bach, [7]

References and further Reading:

- [1] Johann Sebastian Bach Biography in Encyclopedia of World Biography

- [2] A detailed Johann Sebastian Bach biography, at Baroquemusic.com

- [3] Glen Gould plays Bach Partita #2

- [4] Felix Mendelssohn – Child Prodigy of the Romantic Era, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works of Johann Sebastian Bach at Wikisource

- [6] Johann Sebastian Bach at Wikidata

- [7] Craig Wright, Lecture 16. Baroque Music: The Vocal Music of Johann Sebastian Bach, YaleCourses @ youtube

- [8] Geck, Martin (2006). Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work. Orlando: Harcourt.

- [9] Geiringer, Karl (1966). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Culmination of an Era. New York: Oxford University Press.

- [10] Williams, Peter (2003). The Life of Bach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- [11] Timeline for composer Johann Sebastian Bach, via Wikidata