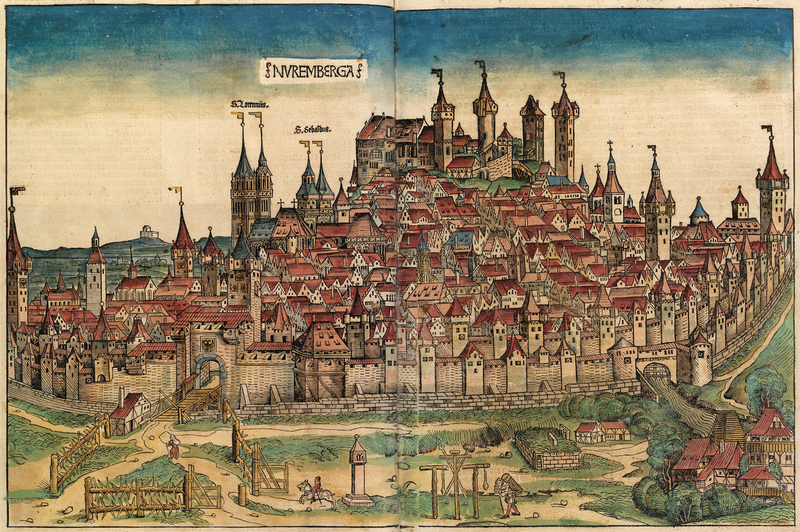

Woodcut of Nuremberg, Nuremberg Chronicle

On December 23, 1493, the German version of the Nuremberg Chronicle – in German ‘Schedelsche Weltchronik‘ – was published. It is one of the best-documented early printed books – an incunabulum – and one of the first to successfully integrate illustrations and text. Moreover, it was the most extensively illustrated book of the 15th century. OK, unless you are not a book history afficionado, a bibliophile eccentric or a historian with focus on early German Renaissance, you might have never heart of today’s subject, the Nuremberg Chronicle. But, be reassured, it is worth while.

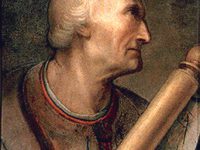

Hartmann Schedel and the City of Nuremberg

Nuremberg was one of the largest cities in the Holy Roman Empire in the 1490s, with a population of between 45,000 and 50,000. Although dominated by a conservative aristocracy, Nuremberg was a center of northern humanism. The author of the Nuremberg Chronicle, Hartmann Schedel, was born in Nuremberg in 1440 as the son of the wealthy merchant of the same name. Hartmann Schedel was enrolled at the University of Leipzig at the age of 16 and became Baccalaureus there in 1457. In 1459, he obtained the Magister artium (Master of Arts) and attended lectures in law and canon law. In 1459 he began to build up an extensive collection of songs. In 1461, he joined the humanistic circle around Peter Luder and made copies of his teaching texts, which were presented in Leipzig from 1462 onwards. Hartmann Schedel received the lower orders in 1462. At the end of 1463, he followed Peter Luder to Padua, probably also in agreement with his thirty years older cousin, who at the time was working as a city doctor in Augsburg, Hermann Schedel (1410-1485), who advised Hartmann during his studies. At the University of Padua, Hartmann studied medicine as well as anatomy and surgery and received his doctorate in medicine in 1466. Parallel to medicine, he had also attended lectures in physics and Greek and was thus one of the first Germans ever to gain access to the Greek language. In the summer of 1466 he returned to Nuremberg to spend the next few years travelling, collecting and copying books.

The Nuremberg Chronicle

In Nuremberg Hartmann Schedel was among the wealthy and respected citizens. Schedel’s major work, the illustrated account of world history in the Nuremberg Chronicle, was first published in Nuremberg in 1493 in a Latin and a German version. According to an inventory done in 1498, Schedel’s personal library contained 370 manuscripts and 670 printed books, which was a fortune in these times. To compose the text of his “World Chronicle“, Hartman Schedel used passages from the classical and medieval works of his collection. He borrowed most frequently from another humanist chronicle, Supplementum Chronicarum, by Jacob Philip Foresti of Bergamo. It has been estimated that about 90% of the text is pieced together from works on humanities, science, philosophy, and theology, while about 10% of the Chronicle is Schedel’s original composition. Thus, the Nuremberg Chronicle, is an early Remix or Mashup.

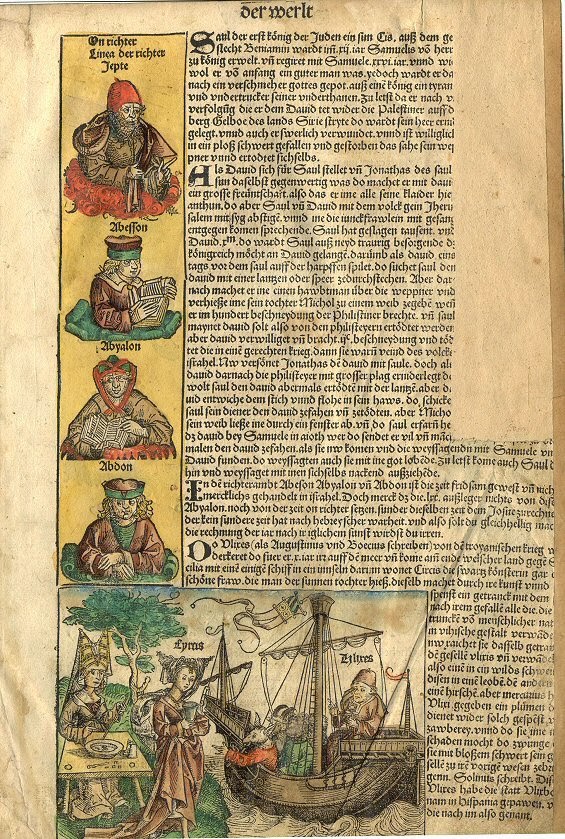

This page of the Nuremberg Chronicle describes “Saul, the first king of the Jews”, David, Samuel, Jonathan, and others.

An Illustrated World History

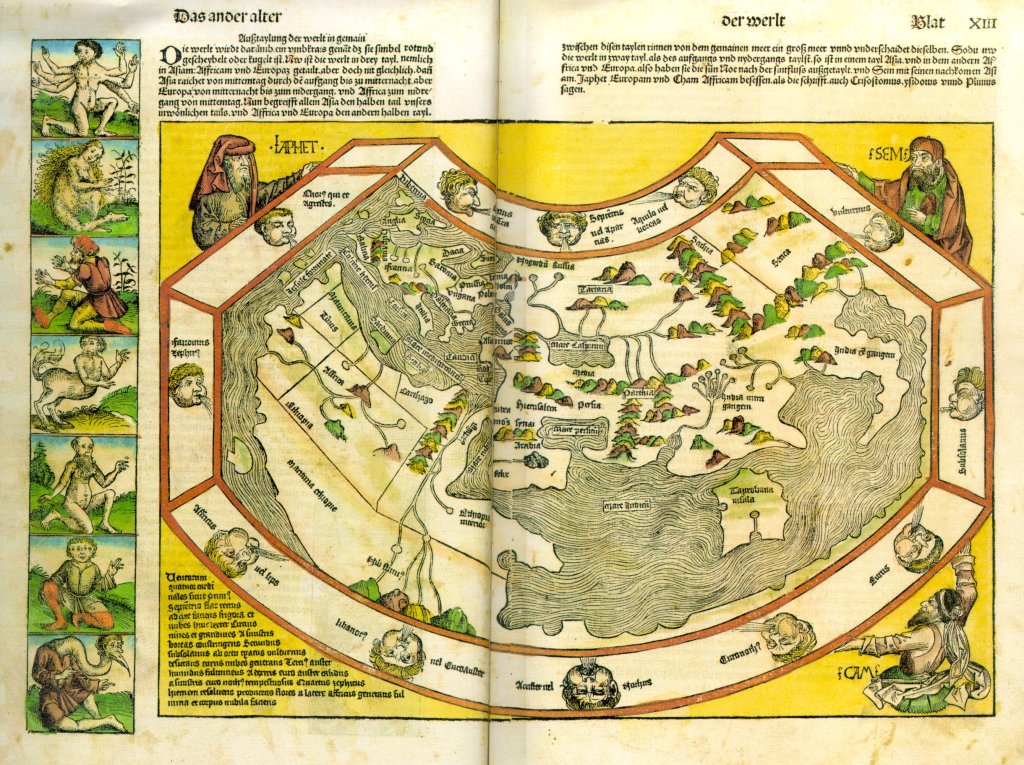

The Chronicle itself is an illustrated world history, in which the contents are divided into seven ages. The First age starts with the creation of the world and ends with the Deluge, followed by the Second age that covers the time until the birth of the patriarch Abraham. The Third age of the world ends with the reign of King David and the Fourth age ends with the Babylonian captivity of the Jews. The Fifth age ends with the birth of Jesus Christ, followed by the Sixth age until present day (1493 AD), followed by an outlook on the Seventh age, when the end of the world and the Last Judgement will come. The large workshop of Nuremberg’s leading artist of the time, Michael Wolgemut provided the unprecedented 1,809 woodcut illustrations. But, as usual in these early times of printing, woodcuts as e.g. for city scapes were reused on several occasions in the book, which finally leads to 645 unique woodcuts. For example, the woodcut that is used to represent Damascus is used to represent Verona and is also used to represent Mantua and Naples elsewhere in the work. Some see evidence that famous Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer helped to prepare several of the woodcuts, as he was an apprentice of Wolgemut in these days.[4] Among the illustrations are 29 double-page city views and two double-page maps: a world map and a map of Europe. On the world map, America is not yet shown, because the existence of the new continent only became known after Amerigo Vespucci had reported on his South America expedition in 1501/1502.[5]

World map (sheet 12v/13r): “This one is therefore called an umbkrais because it is simply rotund and rounded or spherical.” The corners show the biblical progenitors of Europe, Asia and Africa: Japhet, Sem and Cham.

An Early Best Seller

The illustrations in The Nuremberg Chronicle were not only its most important selling point, they were actually the reason for its being. It was the illustrator and engraver Michael Wolgemut who conceived the idea of preparing a profusely illustrated world history. He tried to get his friend, the printer and publisher Anton Koberger to undertake it, but Koberger felt it was too expensive and risky a project, so Wolgemut obtained the support of two wealthy patrons, the Nuremberg merchants Sebald Schreyer and his son-in-law Sebastian Kamermeister, whereupon Koberger agreed to do the printing. The Chronicle was first published in Latin already in July 1493. A German translation followed quickly and an estimated 1400 to 1500 Latin and 700 to 1000 German copies were published overall. Approximately 400 Latin and 300 German copies survived into the twenty-first century. Many copies of the book are also colored, with varying degrees of skill; there were specialist shops for this. The coloring on some examples has been added much later, and some copies have been broken up for sale as decorative prints. The popularity of the book is shown by the fact that there were five editions in only eight years. The reasons for its success are not difficult to see. It contained more illustrations than any book previously printed from movable type, which was enough to make it a “best seller.” Its subject matter also had wide appeal, for history has always been a popular subject. A copy sold in London in 1495 cost 66 shillings 8 pence. The printing of the World Chronicle, which caused immense costs, was not a publishing success, for in 1509 there were still 571 copies in stock. The market value of copies still known today depends on their state of preservation. An excellently preserved copy was auctioned in London in 2010 for about 850,000 US dollars. A copy with two thirds of the pages missing was offered for 35,000 US dollars in 2011.

Anton Koberger – Printer and Publisher

The publisher and printer of the Nuremberg Chronicle was Anton Koberger, the godfather of Albrecht Dürer, who in the year of Dürer’s birth in 1471 ceased goldsmithing to become a printer and publisher. He quickly became the most successful publisher in Germany, eventually owning 24 printing presses with more than 100 craftsmen and having many offices in Germany and abroad, from Lyon to Budapest.

Jeffrey F. Hamburger, The City as Signifier: Nuremberg in the Nuremberg Chronicle, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The (digitized) Nuremberg Chronicle from Morse Library, Beloit College

- [2] Digitized Colored Latin Version of the Nuremberg Chronicle at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

- [3] John Russel, The Nuremberg Chronicle, of the University of Rochester, Library

- [4] Albrecht Dürer – Master of Northern Renaissance, SciHi Blog

- [5] Amerigo Vespucci and the New World, SciHi Blog

- [6] Hartman Schedel at Wikidata

- [7] Schedel’sche Weltchronik at Wikisource

- [8] Jeffrey F. Hamburger, The City as Signifier: Nuremberg in the Nuremberg Chronicle, The Morgan Library & Museum @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of Incunabula, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell's Ghost