Trotula of Salerno

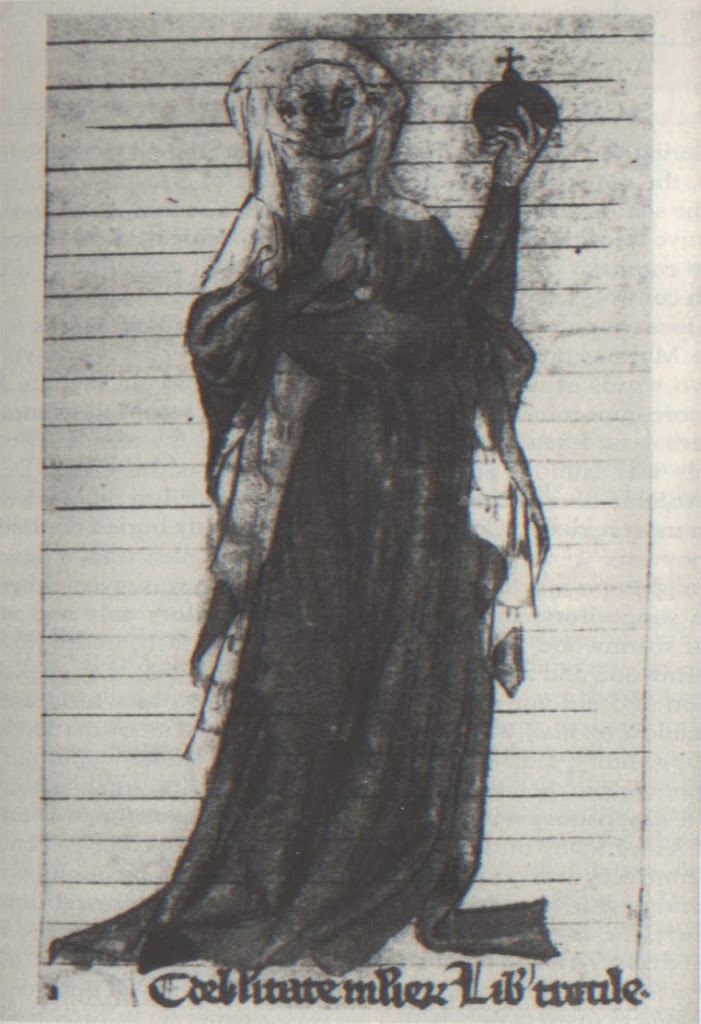

from a manuscript c. the late 12th or early 13th century

Although neither her birthday nor her date of death is known to us, today we want to point out a rather prominent woman in science of which you might never have heard of unless you know your way around in the history of medicine. Trotula of Salerno lived in the 11th or 12th century AD and was a female physician, alleged to have been the first female professor of medicine, teaching in the southern Italian port of Salerno, which was at that time the most important center of medical learning in Europe.

The School of Salerno

In the high-medieval period Salerno was “the most important center for the introduction of Arabic medicine into Western Europe”[1]. The School of Salerno, the Schola Medica Salernitana was the world’s first medical school. It was the most important source of medical knowledge in Western Europe at the time. Arabic medical treatises, both those that were translations of Greek texts and those that were originally written in Arabic, had accumulated in the library of Montecassino, where they were translated into Latin. In this way the received lore of Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscorides was supplemented and invigorated by Arabic medical practice, known from contacts with Sicily and North Africa. As a result, the medical practitioners of Salerno, both men and women, were unrivaled in the medieval Western Mediterranean for practical concerns.

The Life of Trotula of Salerno

Salerno favored the development of what would become the three most important specialized texts on women’s medicine in medieval western Europe. Only very little is known about the life of Trotula of Salerno. She may have belonged to the wealthy di Ruggiero family and may have been married to the physician Johannes Platearius and had two sons. Some scholars believe that both Trotula and her husband authored practica brevis, a work that discusses medical diseases. Trotula is alleged to have written a major work on women’s medicine in medieval Europe, On the Diseases of Women (De passionibus mulierum). She is also alleged to have been the first female professor of medicine and the first female gynecologist. Some scholars assert that Trotula taught at the School of Salerno, earning the title of Magistra Medicinae. At least the evidence that numerous women have graduated from the School of Salerno since its inception validates the fact that Trotula herself attended the institution.

From Chaucer to Gender Questions

As there is little documented evidence about Trotula, there has been much conjecture as to what happened within her life. There are many that believe that she was a revolutionary woman that existed and was indeed one of the first female medical figures. There is further evidence that Trotula existed within the literature that came out of the middle ages. Geoffrey Chaucer in his widely known Canterbury Tales [5] references Trotula’s works in his Wife of Bath prologue.[6] Within the prologue the Wife of Bath talks about her fifth husband and the books that he reads constantly. One of the books that Chaucer has him reading is a work by Trotula, The Trotula Major, and it is implied that even the Wife herself was very familiar with the practices presented in this book. Even though Trotula’s authorship has never been satisfactorily established, feminist medical historians are convinced that she existed because of the connotations of the word “trot” that can be found within her name. A trot was specifically a woman who trotted for a living, she was too old to be attractive and in her business she taught tricks, tips and lessons about women’s sexual pleasure. When in 1566, Caspar Wolff published his own edition of Trotula, authored by “Eros Juliae”, this changing of her name fueled the belief that Trotula was not a woman but a man. Since then, Trotula’s gender and existence has become a subject of debate amongst scholars.

Illustration from Passionibus mulierum curandorum or Trotula major

Trotula’s Works

Trotula’s works are considered the”most widely circulated medical work on gynecology and women’s problems, found in Latin, French, English, German, Flemish, Catalan. The 126 manuscripts of the Trotula that are found represent only a small portion of the original number that circulated around Europe from the late 12th century to the end of the 15th century. Nevertheless, the most important evidence of her existence are her writings. Trotula’s writings are a collection of medical advice, in which she advised women on conception, menstruation, pregnancy, caesarian sections and childbirth. Moreover, she gives general medical advice for treating snakebites, curing bad breath and lightening freckles. Trotula’s radical ideas on conception shocked the medical and social community, because she believed that men and women both have physiological defects that cause conception difficulties. The woman may have a defect of the womb and the man may have a defect in the seed or his delivery. To admit that a man could be responsible for infertility was a daring notion at that time. She also believed that women should not suffer unrelenting pain during childbirth. During childbirth, she advocated the use of opiates produced by plants to dull the pain of labor. This contradicted Christian beliefs that a woman should suffer the pain of childbirth, because of the sin of Eve.[2,3]

Trotula’s Legacy

Until the 16th century, Trotula major in particular was regarded as the standard work in the medical faculties of Europe. In addition, the ensemble became part of folk medicine and legends about the person of the Trotula began to circulate. In 1544 the first printed edition of the Passionibus mulierum was published in Strasbourg as part of the anthology Experimentarius medicinae, which also contained the Physica Hildegard of Bingen among other scientific treatises.

Frank Snowden. 2. Classical Views of Disease: Hippocrates, Galen, and Humoralism, [8]

References and Further Reading

- [1] Benton, John F. “Trotula, women’s problems, and the professionalization of medicine in the Middle Ages”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 59.1 (Spring 1985):33

- [2] Trotula of Salerno at Kings College

- [3] Bois, Danuta. “Distinguished Women of Past and Present: Trotula of Salerno.” 1996

- [4] Reese, Lyn. “Notable Women.” 1994

- [5] Geoffrey Chaucer – the Father of English Literature, SciHi Blog

- [6] Modern Translation of the Wife of Bath’s Tale and Other Resources at eChaucer

- [7] Trotula of Salerno at Wikidata

- [8] Frank Snowden. 2. Classical Views of Disease: Hippocrates, Galen, and Humoralism, Epidemics in Western Society Since 1600 (HIST 234), 2011, YaleCourses @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of Italian Women Scientists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: 10 Women Who Changed Our Lives for the Better but Were Written Out of History - Mall Hunters

Pingback: 10 Girls Who Modified Our Lives for the Higher however Have been Written Out of Historical past - Social Love

I believe Monica Green has settled the question of Trotula’s gender in her research and publications. Trotula was definitely a woman, and possibly held the chair of Medicine at the Schola Medica Salernitana.

Pingback: 10 Women Who Changed Our Lives for the Better but Were Written Out of History – Updated Reports