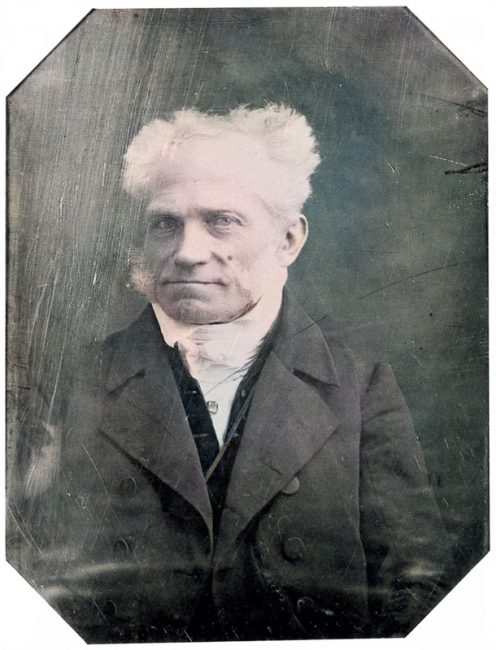

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

On February 22, 1788, famous and most influential German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was born. He is best known for his book, The World as Will and Representation, in which he claimed that our world is driven by a continually dissatisfied will, continually seeking satisfaction.

“It is the courage to make a clean breast of it in the face of every question that makes the philosopher.”

— Arthur Schopenhauer, Letter to Johann Wolfgang v. Goethe (1819)

Early Years

Arthur Schopenhauer was born in Danzig (now Gdansk) on the 22nd of February 1788, as son of the merchant Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer, and Johanna Troisner. At age 17, his father placed him in a business school in Hamburg. Being apprenticed to merchants in Danzig in 1804 and afterwards in Hamburg, the expectation of his father was that Arthur should take over the family’s business. But Arthur Schopenhauer had different plans for his life. After his father’s death, he enrolled in a gymnasium in Gotha. He was a very gifted student and made so much progress that in two years he was able to read Greek and Latin with fluency. In October 1809 he entered the University of Göttingen as a student of medicine There he studied metaphysics and psychology under Gottlob Ernst Schulze, who advised him to concentrate on Plato and Immanuel Kant.[5] He later received the degree of doctor of philosophy from the University of Jena in 1813 in absentia, and in the same year the press at Rudolstadt published his first book, Über die vierfache Wurzel des Satzes vom zureichenden Grunde (On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason).

On Vision and Colours

In 1813, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe invited Schopenhauer for research on his Theory of Colours.[6] Although Schopenhauer considered colour theory to be a minor matter, he accepted the invitation out of admiration for Goethe. Nevertheless, these investigations led him to his most important discovery in epistemology: finding a demonstration for the a priori nature of causality. The difference between the Immanuel Kant’s approach and Schopenhauer was this: Kant simply declared that the empirical content of perception is “given” to us from outside, an expression with which Schopenhauer often expressed his dissatisfaction. He, on the other hand, was occupied with: how do we get this empirical content of perception; how is it possible to comprehend subjective sensations limited to my skin as the objective perception of things that lie outside of me? Causality is therefore not an empirical concept drawn from objective perceptions, but objective perception presupposes knowledge of causality. He set out his theory of perception for the first time in On Vision and Colors, published in 1816.

The World as Will and Representation

“The effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence.”

— Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation (1819)

In 1814, Schopenhauer began his seminal work The World as Will and Representation (Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung). Schopenhauer believed that Kant had ignored inner experience, as intuited through the will, which was the most important form of experience. Schopenhauer saw the human will as our one window to the world behind the representation; the Kantian thing-in-itself. He believed, therefore, that we could gain knowledge about the thing-in-itself, something Kant said was impossible, since the rest of the relationship between representation and thing-in-itself could be understood by analogy to the relationship between human will and human body. According to Schopenhauer, the entire world is the representation of a single Will, of which our individual wills are phenomena. In this way, Schopenhauer’s metaphysics go beyond the limits that Kant had set, but do not go so far as the rationalist system-builders who preceded Kant. For Schopenhauer, human desire was futile, illogical, directionless, and, by extension, so was all human action in the world.

Fichte and Hegel

“This actual world of what is knowable, in which we are and which is in us, remains both the material and the limit of our consideration.”

— Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation (1819)

In 1818 as lecturer at the University of Berlin Schopenhauer had the opportunity to visit Johann Gottlieb Fichte‘s famous philosophy lectures for two years, which he attended with a spirit of opposition.[4] Schopenhauer scheduled his lectures to coincide with those of the famous philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whom Schopenhauer described as a “clumsy charlatan“.[7] However, only five students turned up to Schopenhauer’s lectures, and he dropped out of academia.

Schopenhauer in 1815, second of the critical five years of the initial composition of Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. Portrait by Ludwig Sigismund Ruhl

His Poodle Atman

Leaving Berlin in 1831 in light of a cholera epidemic that was entering Germany from Russia, Schopenhauer moved south and in June of 1833, he settled permanently in Frankfurt am Main, where he remained for the next twenty-seven years. There he entered on the life for which he has become famous: almost in a parody of Kant (who never got out of Königsberg), he dressed in an old-fashioned way and his daily life was defined by a deliberate routine: Schopenhauer would awake, wash, read and study during the morning hours, play his flute, lunch at the Englisher Hof, near city center Frankfurt, rest afterwards, read, take an afternoon walk in the company of his much-loved poodle Atman, check the world events as reported in The London Times, sometimes attend concerts in the evenings, and frequently read inspirational texts such as the Upanishads before going to sleep.

The Cosmic Will is Wicked

“Philosophy … is a science, and as such has no articles of faith; accordingly, in it nothing can be assumed as existing except what is either positively given empirically, or demonstrated through indubitable conclusions.”

— Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena (1851)

Schopenhauer’s system of philosophy was based on that of Kant’s. He did not believe that people had individual wills but were rather simply part of a vast and single will that pervades the universe: that the feeling of separateness that each of has is but an illusion. So far this sounds much like Baruch Spinoza‘s point of view or the Naturalistic School of philosophy’s view. The problem with Schopenhauer, and certainly unlike Spinoza, is that, in his view, “the cosmic will is wicked … and the source of all endless suffering.” Schopenhauer saw the worst in life and as a result he was dour and glum. Believing that he had no individual will, man was therefore at the complete mercy of all that which is about him. His theories on aesthetics and ethics, pointing to the negation of the will as liberation, his “pessimistic” world-view that regarded nonbeing more highly than being, and his conception of music as the highest of the arts all exercised a powerful influence on both Wagner and Nietzsche.[8]

Death

In the intervening years he had written several works including On the Will in Nature (1836), The Freedom of the Will (1841), and On the Basis of Morality (1841). Although an Essay on the Freedom of the Will had been recognized through the awardance of a cultural prize in Norway in 1839 he was into his sixties when the publication of his collection of essays Parerga and Paralipomena (i.e. Additions and Omissions, in 1851) really brought public attention to his life’s work. Schopenhauer had a robust constitution, but in 1860 his health began to deteriorate. On 21st September 1860, Schopenhauer rose in the morning and sat down alone to breakfast; shortly afterwards his doctor called and found him dead in his chair.

“The truth can wait, for she lives a long life.”

— Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Will in Nature (1836)

Why Study Schopenhauer and the World with Richard Bell, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Arthur Schopenhauer biography at European Graduate School

- [2] Arthur Schopenhauer in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [3] Arthur Schopenhauer at Bluepete.com biographies

- [4] Johann Gottlieb Fichte and the German Idealism, SciHi Blog, May 19, 2013.

- [5] Immanuel Kant – Philosopher of the Enlightenment, SciHi Blog, February 12, 2014.

- [6] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and his Theory of Colours, SciHi Blog, August 28, 2015.

- [7] Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel and the Secret of his Philosophy, SciHi Blog, August 27, 2012.

- [8] God is Dead – The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, SciHi Blog, October 15, 2012.

- [9] The works of Schopenhauer, via WikiSource

- [10] Arthur Schopenhauer at Wikidata

- [11] Arthur Schopenhauer at Reasonator

- [12] Why Study Schopenhauer and the World with Richard Bell, University of Nottingham @ youtube

- [13] Timeline for Arthur Schopenhauer, via Wikidata