Thomas Cole: The Course of Empire Destruction, 1836,

thought to be painted after the sack of Rome

On September 4, 476 AD, Germanic soldier and military leader Flavius Odoacer, who led the revolt of Herulians, Rugians, and Scirians soldiers entered Rome and deposed the last Roman Emperor Romulus Augustulus. Odoacer proclaimed himself as ruler of Italy and thus, by convention, the Western Roman Empire is deemed to have ended…

The Roman Empire

Of course, the Roman Empire including all her infrastructure did not disappear on a single day, but September 4, 476 AD marks the end of the succession of Roman Emperors in the western part of the empire. A succession that started with emperor Augustus in 27 BC and lasted for almost 500 years until Romulus Augustulus’ deposition in 476 AD. Actually, the eastern part of the Roman Empire did survive almost 1,000 years longer until Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Turks under Sultan Mehmed IIin 1453. According to the encyclopedia, the Roman Empire denotes the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterized by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings around the Mediterranean in Europe, Africa, and Asia. Before the empirial period, a 500-year-old Roman Republic had been destabilized through a series of civil wars. Julius Caesar had been appointment as perpetual dictator (44 BC) paving the way for his heir Octavian, who defeated his competitors in the Battle of Actium (2 September 31 BC) and was granted the honorific “Augustus”, Latin for “majestic,” or “venerable”, by the Roman Senate (16 January 27 BC).[7,8]

The Descent

As the first emperor, Augustus took the official position that he had saved the Republic, and carefully framed his powers within republican constitutional principles. He rejected titles that Romans associated with monarchy, and instead referred to himself as the princeps, “leading citizen”. Nevertheless, Augustus also established the precedent that the emperor over all other legitimate powers of the Roman state controlled the final decisions, backed up by military force. For almost 200 years, the Roman Empire flourished. In the view of the contemporary Greek historian Cassius Dio, the accession of the emperor Commodus in 180 AD marked the descent “from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron” – a famous comment which has led famous historian Edward Gibbon, to take Commodus’ reign as the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire.[9]

Barbarian Invations

In 376 AD, large numbers of Goths, who were refugees from the Huns crossed the Danube towards south. They sought admission to the territory of the Roman Empire, a political institution which, despite having both new and longstanding systematic weaknesses, wielded effective power across the lands surrounding the Mediterranean and beyond. The Empire had large numbers of trained, supplied, and disciplined soldiers, it had a comprehensive civil administration based in thriving cities with effective control over public finances, and it maintained extreme differences of wealth and status including slavery on a large scale. It had wide-ranging trade networks that allowed even modest households to use goods made by professionals a long way away. Among its literate elite it had ideological legitimacy as the only worthwhile form of civilization and a unity based on comprehensive familiarity with Greek and Roman literature and rhetoric. The Goths were exploited by corrupt officials rather than effectively resettled, and they took up arms, joined by more Goths and by some Alans and Huns. In the decisive Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD, Roman Emperor Valens lost much of his army and his own life. All of the Balkan provinces were thus exposed to raiding by the Barbarians, without effective response from the remaining garrisons who were “more easily slaughtered than sheep“.

Economics and Migration Period

Other fundamental problems contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire. In the economically ailing west, a decrease in agricultural production led to higher food prices. The western half of the empire had a large trade deficit with the eastern half. The west purchased luxury goods from the east but had nothing to offer in exchange. To make up for the lack of money, the government began producing more coins with less silver content. This led to inflation. Finally, piracy and attacks from Germanic tribes disrupted the flow of trade. In 410 AD, the Visigoths, led by Alaric, breached the walls of Rome and sacked the capital of the Roman Empire. The Visigoths looted, burned, and pillaged their way through the city. The plundering continued for three days, a devastation which turned out to be actually less physical than psychological but, even so, a wound which went deep into the heart of an already ailing state. For the first time in almost a millennium, the city of Rome was in the hands of foreigners. Wave after wave of Germanic barbarian tribes swept through the Roman Empire. Groups such as the Visigoths, Vandals, Angles, Saxons, Franks, Ostrogoths, and Lombards took turns ravaging the Empire, eventually carving out areas in which to settle down. The Angles and Saxons populated the British Isles, and the Franks ended up in France.

“The decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight,” (Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire)

The campaigns of Roman Emperor Majorian. During his four year reign, Majorian reconquered most of Hispania and southern Gaul.

Removing the Child from the Throne

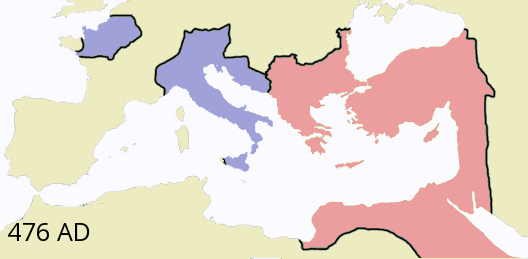

Then on September 4, 476 AD, a date established by the historian Edward Gibbon, the Germanic general Odacer overthrew the last of the Roman Emperors, a boy ironically named Romulus Augustulus. Although Odoacar acted with little respect for formalities — he removed the child from the throne and sent him off to a monastery where he subsequently died — the usurper faced no real opposition, political or military. Actually, barbarian leaders like Odoacer had been the power behind the Roman Emperor for many years, and the German strongman did little more than end the pretense of non-barbarian control of the Roman West. From then on the western part of the Empire was ruled by Germanic chieftain. Roads and bridges were left in disrepair and fields left untilled. Pirates and bandits made travel unsafe. Cities could not be maintained without goods from the farms, trade and business began to disappear. The Eastern Roman Empire survived the turmoil of the so-called migration of peoples, above all because it was the economically healthier and more densely populated part of the empire and remained peaceful within. The Empire was to live on in the East for many centuries, and enjoy periods of recovery and cultural brilliance, but its size would remain a fraction of what it had been in classical times.

Western and Eastern Roman Empires 476AD

Aftermath

Under Justinian, the last Roman emperor, whose mother tongue was Latin, and his commander Belisarius, the Eastern Romans were able to recapture large parts of the West (North Africa, Italy, southern Spain), while in the Orient they were able to hold the borders against the Persians with great efforts. However, since the accession of Chosraus I to the throne, the attacks of the Sassanids became increasingly fierce and the intention was to conquer the entire Roman East. This ended the coexistence of the two empires, and a series of devastating wars began. The (East) Roman Emperor was once again by far the most powerful ruler in the Mediterranean and ruled most of the old empire’s territory (with the exception of Britain, Gaul and northern Spain). After Justinian’s death (565), however, the recaptured territories often proved to be untenable in the long term. After a few years, southern Spain fell back to the Visigoths and Italy to the Longobards from 568 onwards.

Clifford Ando, David B. and Clara E. Stern, The Long Defeat: The Fall of the Roman Empire [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Fall of the Roman Empire at Ancient Civilizations

- [2] The Fall of the Roman Empire at rome.info

- [3] The Fall of Ancient Rome at the historylearningsite

- [4] Reasons for the Fall of Rome at about.com

- [5] Maps of ancient Rome and the Roman Empire

- [6] The Fall of Rome: Facts and Fictions from USU 1320: History and Civilization

- [7] Veni, Vidi, Vici – according to Julius Caesar, SciHi Blog

- [8] Augustus and the Foundation of the Roman Empire, SciHi Blog

- [9] Edward Gibbon and the Science of History, SciHi Blog

- [10] The Roman Empire at Wikidata

- [11] Clifford Ando, David B. and Clara E. Stern, The Long Defeat: The Fall of the Roman Empire, University of Chicago, The Oriental Institute @ youtube

- [12] Brown, Peter (2012). Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the making of Christianity in the West, 350-550 AD. Princeton University Press.

- [13] Gibbon, Edward. History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. With notes by the Rev. H. H. Milman. 1782 (Written), 1845 (Revised)

- [14] Halsall, Guy. Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568 (Cambridge Medieval Textbooks)

- [15] Cameron, Averil. The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity. AD 395–700. Routledge 2011

- [16] Ward-Perkins Bryan. The fall of Rome and the end of civilization. Oxford University Press 2005

- [17] Timeline of Roman Emperors, via Wikidata