The Battle öf Lützen (Nov 16, 1632) by by Carl Wahlbom

On November 16, 1632, the Battle of Lützen, one of the most important battles of the Thirty Years’ War, was fought, in which the Swedes defeated the Imperial Army under Wallenstein, but cost the life of one of the most important leaders of the Protestant alliance, the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf, which caused the Protestant campaign to lose direction.

The Thirty Years’ War

The Thirty Years’ War was a series of wars in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, which began with the Second Defenestration of Prague in 1618 and ended with the Treaty of Westfalen in 1648. It was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history. It was the deadliest European religious war, resulting in eight million casualties. Initially a war between various Protestant and Catholic states in the fragmented Holy Roman Empire, it gradually developed into a more general conflict involving most of the great powers. These states employed relatively large mercenary armies, and the war became less about religion and more of a continuation of the France–Habsburg rivalry for European political pre-eminence.

The Prelude

Two days before the battle, on 14 November the Roman Catholic general Albrecht von Wallenstein decided to split his men and withdraw his main headquarters back towards Leipzig.[4] He expected no further move that year from the Protestant army, led by the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus, since unseasonably wintry weather was making it difficult to camp in the open countryside. However, Gustavus Adolphus’ army marched out of camp towards Wallenstein’s last-known position and attempted to catch him by surprise. A skirmish delayed the Swedish advance, thus when night fell the two armies were still separated by about a few kilometres.

Wallenstein, seeing the danger, dispatched a note to General Pappenheim ordering him to return as quickly as possible with his army corps, who immediately set off to rejoin Wallenstein with most of his troops. During the night, Wallenstein deployed his army in a defensive position along the main Lützen-Leipzig road, which he reinforced with trenches. He anchored his right flank on a low hill, on which he placed his main artillery battery. By 9 am the rival armies were in sight of each other. Because of a complex network of waterways and further misty weather, it took until 11 am before the Protestant force was deployed and ready to launch its attack.

The Death of Gustavus Adolphus

Initially, the battle went well for the Protestants, who managed to outflank Wallenstein’s weak left wing. After a while, Pappenheim arrived with 2,000–3,000 cavalry and halted the Swedish assault. This made Wallenstein exclaim, “Thus I know my Pappenheim!”. However, during the charge, Pappenheim was fatally wounded by a small-calibre Swedish cannonball. The cavalry action on the open Imperial left wing continued, with both sides deploying reserves in an attempt to gain the upper hand. Soon afterwards, towards 1:00 pm, Gustavus Adolphus was himself killed while leading a cavalry charge on this wing. In the thick mix of gun smoke and fog covering the field, he was separated from his fellow riders and killed by several shots. His fate remained unknown for some time. However, when the gunnery paused and the smoke cleared, his horse was spotted between the two lines, Gustavus himself not on it and nowhere to be seen. His disappearance stopped the initiative of the hitherto successful Swedish right wing, while a search was conducted. His partly stripped body was found an hour or two later, and was secretly evacuated from the field .

Cornelis Danckerts: Historis oft waerachtich verhael.., 1632. Engraving by Matthäus Merian. Battle of Lützen, Germany (6 November 1632), in the Thirty Year’s War. Large unfolded engraving. Panorama of the battle showing both armies. Cannonades. Explosion in the foreground. At top right the town of Lützen. Latin text: “Typus CRUENTISSIMI ILLIUS PRAELY, IN OVO EXERCITUS REGIS Sueciae cum acie caesarea sub Duce Fridlandiae, cum magna utriusque partis strage et plerorumque Ducum interitu ad LUZAM conflixit, a.d. 6 Novemb Anni 1632”.

Retreat of Wallenstein

By about 3 PM, the Protestant second-in-command Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, having learned of the king’s death, returned from the left wing and assumed command over the entire army. He vowed to win the battle in retribution for Gustavus or die trying, but contrary to popular legend tried to keep the king’s fate secret from the army as a whole. The result was a grim struggle, with terrible casualties on both sides. Finally, with dusk falling, the Swedes captured the linchpin of Wallenstein’s position, the main Imperial artillery battery. The Imperial forces retired back out of its range, leaving the field to the Swedes. The arrival of Pappenheim’s infantry allowed Wallenstein to retreat in good order.

Strategically a Protestant Victory

The body of Gustav II Adolf was plundered of its clothes and gold jewellery and left on the battlefield dressed only in his shirts and long stockings. His buff coat was taken as a trophy to the emperor in Vienna. It was returned to Sweden in 1920, in recognition of relief efforts by the Swedish red cross during and after the First World War. Strategically and tactically speaking, the Battle of Lützen was a Protestant victory. Having been forced to assault an entrenched position, Sweden lost about 6,000 men including badly wounded and deserters, many of whom may have drifted back to the ranks in the following weeks. The Imperial army probably lost slightly fewer men than the Swedes on the field, but because of the loss of the battlefield and general theatre of operations to the Swedes, fewer of the wounded and stragglers were able to rejoin the ranks.

Aftermath

The Swedish army achieved the main goals of its campaign. The Imperial onslaught on Saxony was halted, Wallenstein chose to withdraw from Saxony into Bohemia for the winter, and Saxony continued in its alliance with the Swedes. Crucially, Gustavus Adolphus’s death enabled the French to gain much firmer control of the anti-Habsburg alliance. Sweden’s new regency was forced to accept a far less dominant role than it had held before the battle. The war was eventually concluded at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.[1]

In May 1813, the Emperor Napoleon was visiting the 1632 battlefield, playing tour guide with his staff by pointing to the sites and describing the events of 1632, in detail from memory, when he heard the sound of cannon. He immediately cut the tour short and went to conduct his own Battle of Lützen.

Peter Wilson, Lützen: The Great Battles, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Peace of Westphalia and the End of the Thirty Year’s War, SciHi Blog, Oct 24, 2013.

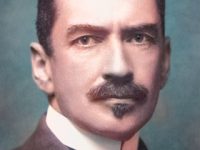

- [2] Gustav II Adolf, King of Sweden, at Britannica Online

- [3] Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, at The New World Encyclopedia

- [4] The Assassination of Wallenstein, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Battle of Lützen at Wikidata

- [6] Peter Wilson, Lützen: The Great Battles, IHSHG History Channel @ youtube

- [7] Schürger, André (2015). The archaeology of the Battle of Lützen: An examination of 17th century military material culture (Thesis). University of Glasgow.

- [8] Wilson, Peter H. (2018). Lützen: Great Battles Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- [9] Battles of the Thirty Year’s War, via Wikidata