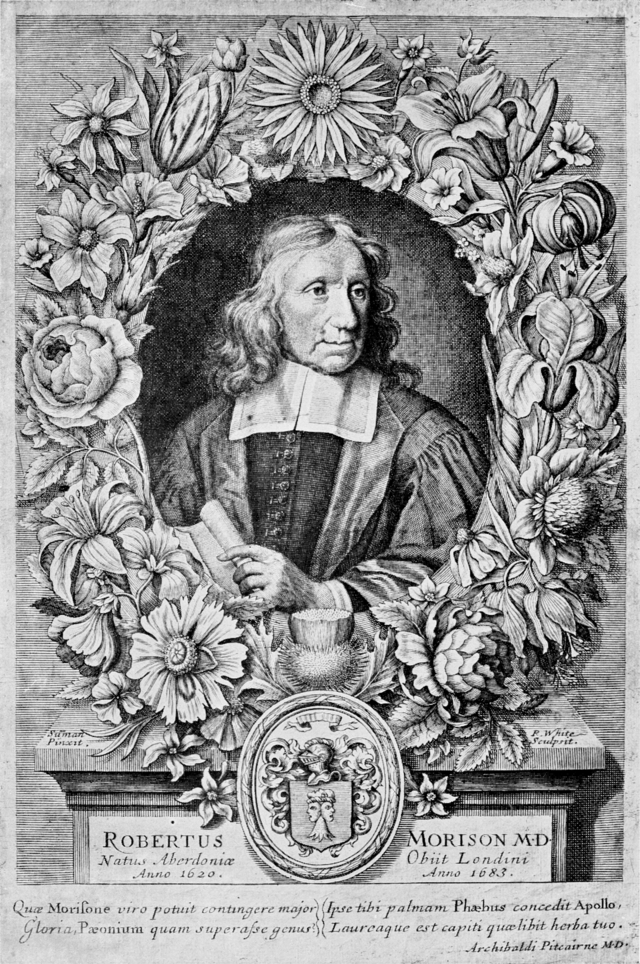

Robert Morison (1620-1683)

On November 10, 1683, Scottish botanist and taxonomist Robert Morison passed away. A forerunner of naturalist John Ray, he elucidated and developed the first systematic classification of plants.

Robert Morison Background

Born in 1620 in Aberdeen, Scotland, as son of John Morison and his wife Anna Gray, Robert Morison was an outstanding scholar who gained his Master of Arts degree and Ph.D. from the University of Aberdeen at the age of eighteen. He devoted himself at first to mathematics, and studied Hebrew, being intended by his parents for the ministry [1] During the English Civil War he joined the Royalist Cavaliers and was seriously wounded at the Battle of the Bridge of Dee during the Civil War. On recovering he fled to France when it became apparent that the cause was lost.

Botany

In France he applied himself to the study of anatomy, zoology, botany, mineralogy, and chemistry, studying Theophrastus, Dioscorides, and in 1648 he took a doctorate in medicine at the University of Angers in Western France and from then on devoted himself entirely to the study of botany. On the recommendation of his tutor Vespasian Robin, the French king’s botanist, he was received into the household of Gaston, Duke of Orleans in 1649 or 1650, as one of his physicians, and as a colleague of Abel Bruyner and Nicholas Marchant, the keepers of the duke’s garden at Blois, a post which he subsequently held for ten years.[1] He was sent by the Duke to Montpellier, Fontainebleau, Burgundy, Poitou, Brittany, Languedoc, and Provence in search of new plants, and seems to have explained to his patron his views on classification.

In 1660, despite inducements to make him stay in France, Morison returned to England at the invitation of the newly restored Charles II, where he became royal physician and Professor of Botany in Oxford in 1669. One of his first publications for the newly revived University Press was the Hortus Regius Blesensis (1669), the catalogue to which Morison added the description of 260 previously un-described plants, although later many were considered only varieties and others were already well known.

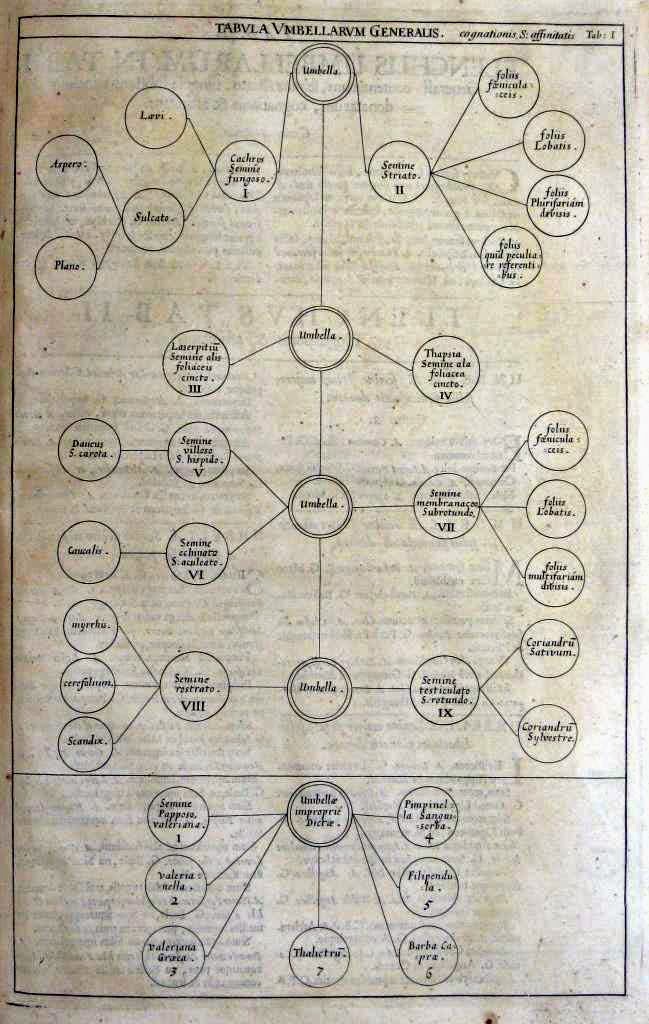

Illustration from Morison’s Plantarum Umbelliferarum Distributio Nova (1672)

Praeludia Botanica

In the same year, Morison published Praeludia Botanica, a work which stressed using the structure of a plant’s fruits for classification. At the time, classification focused on the habitat and obvious properties of the plant and Morison’s criticism of existing botanical systems caused some anger among his contemporaries. In the preface to his Plantarum Umbelliferarum Distributio Nova (1672), Morison gave a definitive statement of the principles of his method and was the first person ever to write a “monograph of a specific group of plants“, the Umbelliferae. Carrot and parsley also belong to the family of Umbelliferae and are now called Apiaceae. They were identified already by Rembert Dodoens as a distinct group for the first time in 1583.[3] Using a classification based on seed characteristics supplemented by differences in vegetative features, Morison divided plants with umbel type inflorescences into different genera of true umbellifers and those which were ‘Umbellae improprie dicto’ from different genera such as Valeriana, Filipendula, and Thalictrum.[2] Morison drew much criticism from his contemporaries as he stated that he had derived his schema from the book of Nature alone and did not mention his debt to Italian botanist Andrea Cesalpino [6] whose system he closely followed. Carl Linneaus [5] wrote about Morison in a 1737 letter:

“Morison was vain, yet he cannot be sufficiently praised for having revived a system which was half expiring. If you look through Tournefort’s genera you will readily admit how much he owes to Morison, full as much as the latter was indebted to Cesalpino, though Tournefort himself was a conscientious investigator. All that is good in Morison is taken from Cesalpino, from whose guidance he wanders in pursuit of natural affinities rather than of characters.”

Morison was fatally injured by the pole of a carriage as he was crossing the street on 9 Nov. 1683 and died the following day.

Tom Owens, BIOPL3420 – Plant Physiology – Lecture 1 [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Morison, Robert,” in Dictionary of National Biography, London: Smith, Elder, & Co., (1885–1900) in 63 vols.

- [2] Robert Morison at the Edward Worth Library

- [3] Rembert Dodoens and the Love for Botanical Science, SciHi Blog

- [4] Royal Botanist Charles Plumier, SciHi Blog

- [5] How a Cobbler became the ‘Princeps Botanicorum’ – Carl Linnaeus, SciHi Blog

- [6] Andrea Cesalpino and the Classification of Plants, SciHi Blog

- [7] Robert Morison at Wikidata

- [8] Tom Owens, BIOPL3420 – Plant Physiology – Lecture 1, SciencexMedia at Global Development @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of 17th Century Botanists via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #18 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #13 | Whewell's Ghost